Make but don’t speak in India

In early January, as part of his much hyped ‘Make in India’ agenda, Prime Minister Narendra Modi unveiled the ‘Start-Up India’ initiative. This ode to venture capitalism is but a complement to the Modi regime’s older and bigger initiative—‘Shut-up India’.

Central to this are attacks on social activists, workers, secular intellectuals, students, minorities and anyone else deemed to be defying, dissenting or claiming freedoms frowned upon by Hindu hyper-nationalists. In Modi’s India a mere rumour that you ate beef could get you killed.

While an assortment of Hindu right-wing storm troopers are flourishing, and at the ready to do the dirty work of the regime, standing by is a repressive and eager-to-please police machinery. Embellishing this is a craven big media, sections of which relentlessly manipulate and replay the you-are-either-with–Modi-or-against-India message.

All of these elements came to the fore in the reprehensible police crackdown on students in Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) on Feb. 12 and the arrest of its left-affiliated students’ union President, Kanhaiya Kumar, on charges of sedition over the alleged shouting of ‘anti-national’ slogans.

For a regime so image conscious, after all the man at the helm fancies suits monogrammed with his own name, it is understandable that it should rely on endless replays of doctored TV footage and a trial by media. It went far enough for a producer from Zee TV to quit in disgust over such footage being played “repeatedly to spread madness and mayhem.”

The same news channel has since targeted Nivedita Menon—the latest in a string of progressive scholars under attack—by selectively splicing together ‘controversial’ bits and pieces from a public talk. And as has become the norm, police complaints and a media witch-hunt are following.

In the meantime, big media is largely refusing to cover or misrepresenting the large-scale police brutality in the University of Hyderabad (UoH) on the 22nd March. UoH has been witnessing protests since the suicide or ‘institutional murder’ of Dalit student Rohith Vemula in January. Dozens of students and faculty have been arrested and the law is being bent but protests continue.

After visiting fellow students and faculty in jail, a UoH student pointedly observes in the video below that the university resembles a prison and the prison a university. She could well be speaking about many other universities and places in India today.

Irrespective of the legal outcomes in any specific case, the idea is to chill dissent, the very essence of democracy, and make a hyper-nationalist common (non)sensibility the norm, dividing and polarizing society.

As much as a battle for freedom of conscience and expression, India is witnessing a battle to save its institutions, from universities to the media and the judiciary, from being fundamentally Modi-fied. The battle lines are well and truly drawn.

A catalogue of assaults on social rights

The assault on freedom on conscience—whether of students, unionists, artists, journalists, filmmakers, or environmentalists—has also been accompanied by a sustained assault on social rights.

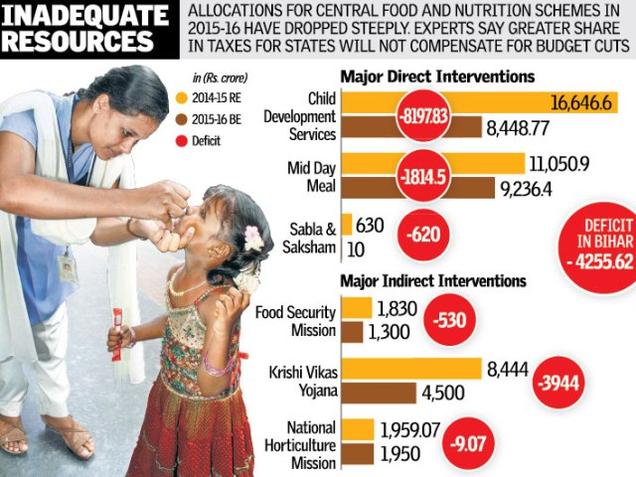

At the very outset, the Modi government sought to weaken India’s national rural employment guarantee scheme—arguably the world’s most ambitious livelihood security programmes. This was accompanied by massive cuts in social spending.

Such has been the scale of cut-backs that late last year, Union Minister Maneka Gandhi publicly criticized fiscal measures that were undermining her ministry’s efforts to battle child malnutrition.

Infographic courtesy The Hindu.

While a political backlash is forcing a rethink of such measures, foreign and domestic capital is being aggressively wooed with a red carpet of sweeping incentives. Modi’s call to ‘Make in India’ has entailed un-making environmental and labour protections, even weakening safeguards against child labour.

No wonder then that in the very shadow of recent police excesses in Delhi, the police forces of Haryana and Rajasthan, both states ruled by the Prime Minister’s party, combined to unleash terror and brutal violence on workers in an industrial zone straddling their borders.

Similarly, in the last few weeks, Chattisgarh, another BJP-ruled state, has been witness to renewed attacks against activists, lawyers and journalists who have been engaged with issues concerning dispossession and state-supported violence targeting tribal communities.

Development Modi-style is also fundamentally anti-democratic. The government’s lack of majority in the second chamber of Parliament stymied efforts at diluting the land acquisition act to make dispossession easier. Having overplayed its hand with Presidential Ordinances, the regime is now resorting to subversion of parliamentary convention.

The latest tactic is evident in the designation of a law pertaining to the dubious unique identification project—essentially a tool for mass surveillance—as a money bill in Parliament. This means the second chamber cannot reject it.

Modi’s rhetoric about good and transparent governance is in fact just that. The Central Information Commission, the guardian of India’s right to information establishment went for the longest time—nearly 10 months—without a Chief Commissioner under this government.

Indeed, even speaking about right to information has become dangerous. In January, a gang led by a legislator from the Prime Minister’s party assaulted social activists in Rajasthan spreading awareness about India’s right to information law. Meanwhile, the regime has been set on diluting the Whistleblower’s Protection Act passed in February 2014.

Azaadi!!

Development in a Modi-fied India implies a stress on aggressive neoliberalism in the economic sphere buttressed by a majoritarian cultural nationalism that seeks to radically reconstitute the social sphere. In the process, the regime is sharpening the many contradictions that are constantly making India.

But as was underlined by elections in Delhi last year and more recently in Bihar, Modi’s political fortunes are by no means assured. But more important for Indian democracy perhaps is the groundswell of outrage and public mobilization across the country, especially on campuses.

The demand for azaadi—freedom—‘not from but within India’ is becoming a rallying cry. Even as universities become intensely policed students are becoming increasingly nimble, labour cracked down upon is finding new ways of organising, activists once beaten are more resilient, and the tighter dissent is gripped the more it is defiant.

As much as his successes, Modi’s failures, now piling up steadily, will intensify social and political economic conflicts and struggles. New visions, ideas and energies emerging from these struggles offer the promise of renewing social movements and progressive forces. And solidarity that can strengthen these struggles is the need of the hour. Indeed, India is really ‘starting-up’ though not quite in the way Modi and co. expected.