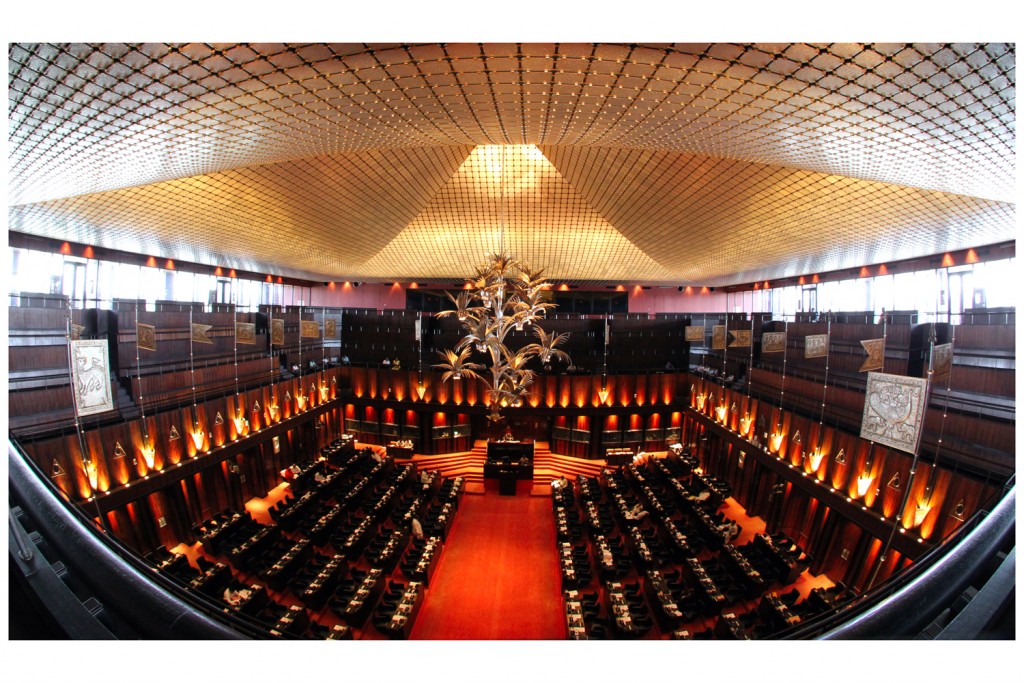

Photo courtesy Article 14

The 8th parliament has been convened after a roller-coaster election. The indelible ink still stains my little finger, but my optimism about the national list wore off some time ago.

The results were a mixed bag; Sri Lanka sent home some notorious politicians, but it also returned a remarkable number (one in particular, straight from remand prison). While the United National Front (UNF) and Ilankai Thamil Arasu Katchi (ITAK) gained the ground that the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA) lost, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) under-performed; their showing seemed not to correspond to their public appeal prior to the election. On both sides, there are young, new faces entering parliament, but the hope this inspired has been marred by the events surrounding the National List candidates appointed by parties.

What is the National List for?

In our electoral system, the National List MPs comprise 29 members who will enter parliament without having to contest elections. The list was introduced primarily to bring in experts and professionals from various fields, whose knowledge and skills would be useful in parliament – the underlying assumption being that such individuals would not have the time, political know-how, or the requisite popular appeal to successfully contest and win an election. In the same vein, it could also help improve the gender balance of parliament. Women candidates still have had limited electoral success in Sri Lanka; the list ought to help increase female representation in parliament. It was not meant to be a back door through which unpopular – or insecure – politicians might enter parliament without having to contest elections, nor was it meant to be a safety net for defeated politicians to enter the legislature.

The logic behind a national list is sound, although the mechanisms to protect its spirit are not (Section 99A as introduced by the14th amendment effectively allows parties to ignore the lists they have declared and to nominate anyone else, subject to the normal limitations). In Sri Lanka, politicians are generally not seen as being well educated, and so it makes perfect sense to ensure that at least little over 10% of the parliament’s composition is protected by the national list for educated professionals and upstanding members of the public. The aim is that these MPs will make significant contributions to debate in parliament, and according to research done by Manthri.lk, opposition national list MPs in particular seem to have lived up to expectations. Such individuals would probably not take the trouble to fund and run their own campaigns, especially because their chances at election would be slim. Thus – a national list.

Who was on the National Lists, and who ultimately got in?

Of all the political parties at this election, it was the JVP that seemed to approach the National List in the true spirit for which it was intended. Their list comprised a former Auditor General, lawyers, a number of university professors, writers, cartoonists and so on – a mixed bag of professionals who would each bring some unique experience to the country’s primary deliberative body. However, having secured two bonus seats, the party decided to nominate defeated Matara district candidate and former MP Sunil Handunetti through the national list, along with former Auditor General Sarathchandra Mayadunne. The latter has since made his first and last speech in parliament, and has resigned. He has been replaced by yet another defeated candidate.

In stark contrast to the JVP, the UPFA had very few non-politicians on their list to begin with, but they made things worse by nominating seven defeated candidates in their final list.

The ITAK also nominated defeated candidates for both its seats, with the only saving grace being that one is a woman.

The United National Front had a mix of politicians and non-politicians, but did the honourable thing by sticking to its list (for the most part – one defeated candidate from the ACMC made the list). This was in spite of mounting pressure to nominate former MP Rosy Senanayake who was unable to secure a seat from the Colombo District. Anoma Gamage – a woman nominee – will sit in parliament through the UNP, as will Dr. Jayampathy Wickramaratne, a constitutional lawyer.

The National List as a safety net – why is it wrong?

I strongly believe that appointing defeated candidates through the national list undermines the voter’s franchise. The voter does two things with her vote – she casts a preference for a particular candidate (or candidates), but she also casts that vote against all others. The latter was abundantly clear in the presidential election in January, but it also holds true at general elections. Whether voters do it consciously or not, when they mark a preference, they are making a decision to pick one candidate over the other – those of us who voted in Colombo are painfully aware of how tough this decision can be.

Let us then examine how this plays out with a national list. I vote for party A because I like candidate X, who is contesting the election, and Y, who is on party A’s national list. When voting for candidate X, I am also hoping that another candidate (Z) who is contesting from the same party will not get elected. Thus, I cast my vote in the hope that it will directly get candidate X in and keep candidate Z out, and that it will indirectly get Y in through the national list.

Post-election, candidate X wins his seat, candidate Z loses, and party A secures a national list seat – so far I am happy on all counts. However, the party then decides to nominate defeated candidate Z through the national list. Now, I am doubly wronged, because the candidate I did not want (Z – who was fairly defeated at the polls) gets in, and at the expense of the national list member I did want.

I may not have changed my vote even if I knew party A would behave this way, and certainly, Sri Lankan voters know not to have any expectations of political parties; nevertheless, this amounts to nothing more than a deception of the voter. I have been tricked, and my franchise undermined.

Some may argue that parties ought to have the discretion to appoint candidates who may have just had a bad campaign; that failure to garner enough votes is not proof that a politician is unworthy of a seat in parliament. I would respond that in a democracy, victory at an election is the least flawed and most objective measure of the ‘worthiness’ of a politician. Above all, a system by which parties have such discretion in appointments seems to do the voter greater injustice than one in which national lists are closed, to the detriment of a few deserving politicians who may come up short at the polls.

Through this all, the biggest disappointment has been the JVP, whose campaign declared themselves the conscience of the people. They presented the ideal national list to the people, but have since turned their backs on it completely. As a result, they have lost their moral high ground, and cannot express the people’s frustration at the way other defeated candidates (and less ‘worthy’ ones, certainly) have been included by the UPFA.

I am told I am too young to be cynical, but events like these certainly push the public in that direction. The new government has talked of a new constitution, and if such a process does materialize, protecting the spirit of the national list should be high on our priorities.