Photo courtesy Vikalpa

And even the miserable lives we lead are not allowed to reach their natural span. For myself I do not grumble, for I am one of the lucky ones…. Is it not crystal clear, comrades that all the evils of this life of ours spring from the tyranny of the human beings? George Orwell, Animal Farm, (p.5).

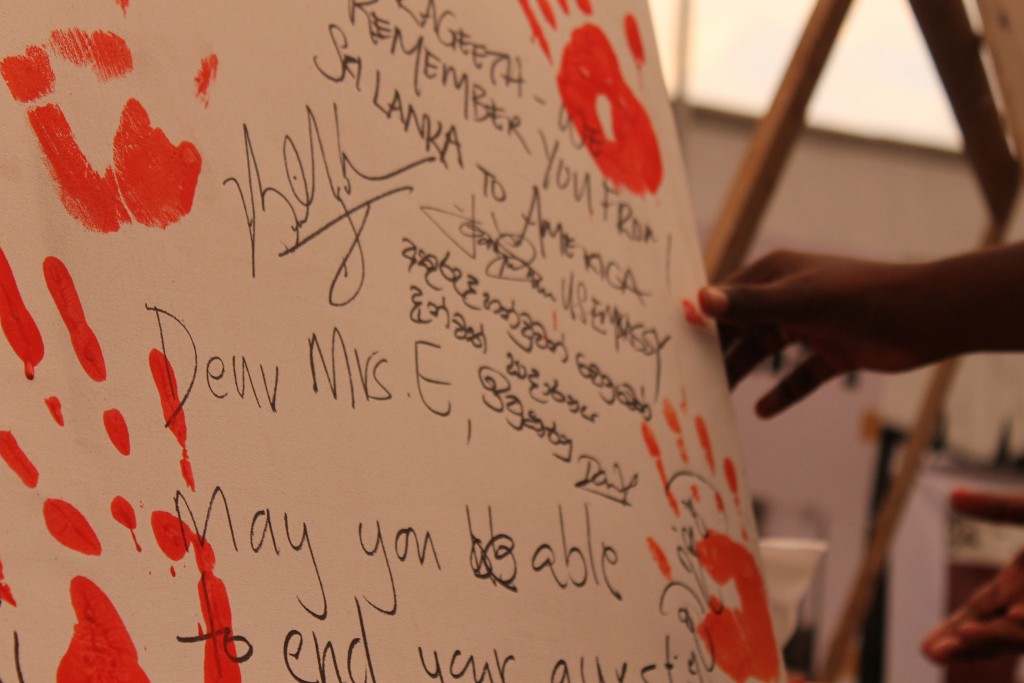

Prageeth Ekneligoda, one of the best political cartoonists this country has ever produced was known for his great talent and political vision. He is now remembered for his disappearance on the night of 24 January, just two days before the 2010 Presidential elections. It was reported that Prageeth had previously been abducted in August 2009 and was released. On that occasion when he was taken by a white van he pleaded with his abductors that he needed to take his medication. He was a chronic diabetic and had undergone a bypass. His abductors had told him that it was of no use for a condemned man to take his medication. However, they let him go. On the second occasion there was no reprieve and he never came home to see his children and wife. They have been waiting for him to return home for five long years.

I had come to know Prageeth in 1986 when we developed a deep comradeship during the most intense period our lives thus far. It was a testing period for all political personalities and activists alike that demanded an unhesitating commitment to our principles. I had already left my academic job in the university to do full time politics. This period had been the prelude to the bloody political battles that engulfed the whole country, a dark and murderous chapter in the political history of Sri Lanka, which continued to the present day even after the military defeat of the Tamil Tigers. The authoritarian United National Party (UNP) government headed by JR Jayewardene and later R Premadasa had launched death squads making this country a killing field. Unlawful abductions and killings of the political opponents had now been introduced to the political process. The Peoples Liberation Front (JVP) had also begun murdering those of us who supported the political rights of Tamil people, starting with Daya Pathirana, the charismatic student leader of the Independent Student Union at Colombo University, abducted and brutally killed. We had formed the Vikalpa Kandayama (Alternative Group), which supported the devolution of political power to the Tamil Community in the North and East. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam (LTTE) with its separatist political agenda had started it’s battles with the Sri Lankan security forces.

It was in these circumstances that Prageeth and I were making a dangerous and precarious journey on foot through miles of thick jungle in the Dambulla area. We had been walking since early morning and by midday we were hungry, thirsty and physically exhausted. I sat on the footpath and told Prageeth that I could not walk anymore. Prageeth got very annoyed with me and asked me how I could preach to others and yet buckle down in the face of difficulties. He put me to shame. Gathering my pride, I stood up and started walking again. We were walking to a farm in the jungle where I would work as a farm laborer, allowing me to hide from the security forces while building and organizing underground political cells.

Prageeth visited my safe houses regularly during this time. For more than six months, my life was totally dependent on him and his integrity, trust and honesty. I knew very little about him at that time beyond the fact that he was a man of great courage. This is how we lived in the political underground, eschewing personal details, family background, or personal origins. We existed at the edge of life, putting our total trust in each other. Unencumbered by the ordinary details of life, we could only depend on each other’s personal qualities and Prageeth’s selfless dedication always shone through. Very often, he walked to save money and skipped meals. He always pretended that he had eaten before he arrived to see me. I still remember his smile, which appeared even in the most difficult of times. He never expected any benefit from the help he gave me, despite the fact that he was putting his own life at risk every time he came to see me. I am alive today because he was there to protect me. I owed him everything.

After I returned to Colombo from Dambulla I never met Prageeth again. It was not possible to continue contact with Prageeth unless it was essential, in keeping with the rule of underground existence, which we lived by. We had exchanged messages every now and then. After my wife Rajani was assassinated by the LTTE in September 1989 I had to flee Sri Lanka with my two young daughters. He had sent me a beautiful painting of my wife through a friend of mine to London. He too survived all odds and had become a husband and father of two children. He had everything to live for.

How was it possible for a person like Prageeth to disappear without any trace? The answer lies in the political and security apparatus that had been created during the war against the LTTE that had suspended even a very little the political liberties hitherto we had enjoyed. The Prevention of Terrorism Act and the Emergency Regulations provided much needed cover for such oppressive structures. This gives the opportunity to create a ‘deep state’ within which many of the abductions and murders are carried out at will. The violations of the rule of law with impunity and the suppression of political dissent had become a fact of daily life and the intimidation that created along with that gave the opportunity to the state to suppress the wishes of the people. This was what happened during the 30-year war against the Tamil tigers and beyond and recently, until the Rajapaksa regime was electorally defeated in the recent Presidential elections.

The deep state targets and eliminates the talented individuals who are able to nurture alternative views and defy the status quo. The murder of Lassantha Wickramatunga in broad daylight showed how such apparatus were capable of carrying out such heinous crimes. Prageeth as a journalist had consistently supported the political rights of the Tamil community, not the LTTE. There are three possible reasons for Prageeth’s disappearance. Firstly, Prageeth was a political cartoonist. Secondly, Prageeth had campaigned for the election campaign of Sarath Fonseka who was the common candidate of the 2010 Presidential election. Thirdly, the previous government always made a strategic mistake of not being able to distinguish those who supported the rights of the Tamil people from those who supported a separate state of the Tamil Tigers. Of these three reasons, which one was more crucial to Prageeth’s disappearance only those who ordered his abduction can tell us.

Very often repressive regimes resort to violence as it gives them very effective results. What would be effective in the short term becomes a haunting nightmare in the long-term when the abductee becomes the living symbol of the political criminality of an authoritarian regime that refuses to answer the question of disappearance to the loved ones. This has happened in the case of Prageeth, as the previous government not only willfully avoided the answer but also fabricated lies to cover up their political criminality. But Sandaya and her children never allowed Prageeth’s memory to fade a way nor let his unresolved fate disappear from the local and international campaign against the atrocities of the previous regime. Sandaya’s unwavering courage and her search for truth and justice is an example for us all. She has refused to be cowed in the face intimidation and blatant lies and has kept the flame of hope alive for her husband.

Hannah Arendt in her The Promise of Politics (2005) explains that ‘Lawlessness means in either case not only that power, generated by men acting together, is no longer possible, but also that impotence can be artificially created. Out of this general powerlessness, fear arises, and from this fear come both the will of the tyrant to subdue all others and preparation of his subjects to endure domination (p.69). The previous regime was able to create such an atmosphere intimidating people against atrocities committed by them. The previous regime’s monstrosity in creating an authoritarian regime that flouted the rule of law made all of our lives precarious. Those who were considered unpatriotic were punishable at will. They had no recourse to legal protection. The regime continuously used their media personnel and institutions to vilify the journalist who were refusing to tow the government’s line. Some journalists were physically attacked on their way to work or home. There were little efforts to find culprits. The previous regime first begun the termination of the right to life of the under world ‘criminals’ in the South. In the North it was suspected ‘terrorists’ who were abducted and disappeared in their thousands. Under various pretexts after killing the criminals the police declared that they had either resisted arrest using firearms ‘forcing’ the police to shoot back and kill them or the criminals had tried to escape from custody. The judicial process was not applied to the so-called ‘criminals’ and the police became both judge and the executioner. There were no investigations and even the cabinet ministers were boasting about the termination of the underworld figures on prime time TV programs.

Many journalists who voice their opinion had to flee the country to save their life. As mentioned before Lasanth Wickramatunga had been gunned even before the victory of the war against the LTTE because he posed a challenge to the government’s propaganda. It was an embarrassment to Sri Lanka when the previous regime went on telling lies at the UNCHR session in Geneva last year, saying that Prageeth had escaped to a European country and had been living away from Sri Lanka. Even a Deputy Minster went on TV to claim that he saw Prageeth in Paris. Even before such lies were propagated there were some partisan journalists who wrote articles undermining the integrity of Prageeth and supporting the view of the government that Prageeth had not been abducted. It is the duty of the current regime to investigate Prageeth’s disappearance and let the family know what happened to him. Until that is done the young lives of his children and wife will continue to be in limbo.

I still remember Prageeth once talking to me about Maxim Gorky’s short story titled ‘My Fellow Traveller’ when we on the way walking to a safe house. I had not read the book then. I thought it would be a tribute my memory of Prageeth to end this article with the following lines that end Gorky’s short story.

‘I never met him again–the man who was my fellow-traveller for nearly four long months; but I often think of him with a good-humored feeling, and light-hearted laughter.

He taught me much that one does not find in the thick volumes of wise philosophers, for the wisdom of life is always deeper and wider than the wisdom of men’.