Photograph courtesy The Independent

Mr Akashi was absolutely right when he urged flexibility and reform on the Sri Lankan government and sounded the alarm of serious consequences in Geneva March 2014 (that’s 75 days away, folks) if it failed to shift in the right direction. He did get one thing wrong though. There is neither a “Central government” nor a “Northern provincial government” in Sri Lanka. Those categories and that terminology pertain to a federal system such as that of India. Constitutionally what we have is a unitary state form in which there is one government and power has been shifted outwards and downward, in specific respects, to provincial councils or administrations. That is the crucial distinction between federalism and devolution. Of course Mr Akashi’s political Freudian slip indicates the view of Sri Lanka and attitude towards it in a large segment of the international community. The treatment of Sri Lanka as already containing two power centres, two capitals, does not help the battle for devolution and only reinforces the propaganda of the Sinhala hawks within and outside the State.

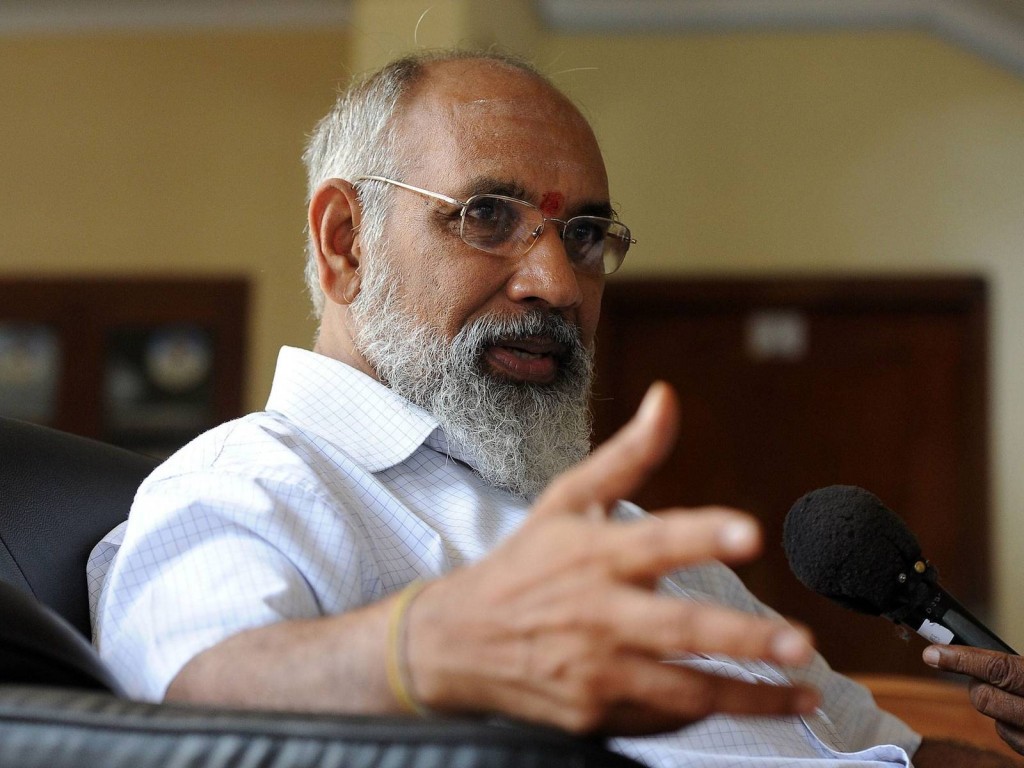

What looks like a sideshow, namely the growing confrontation between Chief Minister Wigneswaran and Governor Chandrasiri, is much more than that. It is the thin end of the wedge of a clash of two projects: that of the strategy of escalating globalisation by Tamil nationalism and narrowing of space by the defence establishment which seems to drive much of state policy at a subterranean level.

With the recent election and the end of the stage of war as well as a post war political vacuum, Governor Chandrasiri should logically have been eased out as the gesture would have marked a new beginning. However, the security establishment seems to wish to emphasise continuity rather than signal discontinuity, perhaps to assuage the apprehensions of the soldiery. This is quite understandable given the invocation of Prabhakaran and the LTTE by ‘moderate’ TNA members during the election campaign and after.

The answer would have been to appoint a Sinhalese able to balance between the armed forces and the Provincial council, as well as between the state and the diplomatic/donor community. The former head of the government’s Peace Secretariat, Prof Rajiva Wijesinha comes readily to mind. If the requirement were for someone with a military background, there are at least two former army commanders with liberal credentials and ambassadorial experience, Generals Gerry de Silva and Srilal Weerasooriya. So far the government has chosen not to exercise these options and may not even be aware they exist.

That said the Northern Provincial Council should not have passed resolutions calling for the removal of the governor and the retrenchment of the armed forces, so soon after taking office. These could demands have been urged at negotiations –perhaps backchannel ones—rather than publicly demanded. Furthermore the TNA leader should not have announced to Mr Akashi that the government has three months to act on Tamil grievances and should it fail to do so the TNA would initiate a non-violent campaign of agitation. Mr Akashi, who has very considerable international experience how these things go, rightly counselled patience.

It is against this backdrop that the inaugural Budget speech of Chief Minister Wigneswaran delivered on December 10th 2013 is especially worrying, but it would have given cause for serious concern in any context.

Justice Wigneswaran complains that the system of provincial councils applies to the entire island. That was not only a decision of President Jayewardene who did not wish to be seen to confer special status on the North and East which would then become the target of majoritarian resentment, and wanted instead to give devolution greater acceptability and strategic anchorage by creating a constituency for it among the Sinhalese, it is even more importantly, the consistent stand taken by progressive opinion in the south for decades, ranging from the Marxist Left in the 1940s to the populist social democratic Vijaya Kumaratunga in the mid 1980s. In the face of a savage JVP insurgency, the provincial council election was held in late 1988 only because the path had been prepared by the holding of such elections throughout that year in the midst of a bloody Southern civil war between pro-and anti-devolution political forces, in the island’s other provinces. Many more died in that Sinhala-on-Sinhala civil war than did in the famous final days of the war against the LTTE.

Justice Wigneswaran protests that “…But the then Government made the Provincial Council System applicable to the whole Island and thus stultified the whole concept of power sharing essential for the Tamil speaking Northern and Eastern Provinces. Thereby nothing was given specially for the Northern or Eastern Provinces when power sharing was urgently needed by them rather than the other Provinces. In fact the political need to devolve power for the North and East was effectively scuttled. The political needs, aspirations and the special interests of the people of the Northern and Eastern Provinces were thus overlooked.”

One fails to understand how the conferment of provincial councils on the other provinces “stultifies” the sharing of power with the Tamil people of the North and East. How can the “political needs, aspirations and special interests” of the people of the North and East have been “overlooked” by conferring a similar measure of autonomy on the other provinces? His logic seems to be that justice for the Tamils is possible only when it is exclusive and unique. In a democracy, the special interests of the people of a province, be it ethnic, religious, linguistic, cultural or economic, can and usually will find expression in the specific policy mix of that Council. It is not necessary that it should be the only such autonomous entity in the entire country!

The answer of Tamil nationalist ideologues may be that Kashmir has special status as does Quebec. However, had Quebec been separated from France a few miles and the danger of irredentism been real, the degree of autonomy may have been significantly different. That this is not mere counterfactual speculation is best evidenced by the sharp reaction of Canada to Gen Charles De Gaulle’s strident reference to Quebec. As for Kashmir, the history of the accession and the pledge of a referendum made in the UN by Shri Nehru give a unique dimension to the problem.

The complaint registered by Justice Wigneswaran is important for two reasons. Firstly it reveals that he is questioning and re-opening the fundamental coordinates of the Indo-Lanka accord of 1987 and the progressive Southern consensus, clearly indicating that the Tamil project goes well beyond that agreement and that consensus. Secondly it betrays the long standing Tamil sense of being unique and deserving of special privileges not enjoyed by the rest of the country’s citizenry or areas.

He says “The Provincial Council System, it must be noted has been identified by all as a means to devolve power to the periphery. But the Thirteenth Amendment in fact has strengthened the hands of the Executive President and widened his powers.”

This is significant in that the target of the criticism is not the Southern hardliners on the charge of seeking to sabotage or abolish the Thirteenth amendment. It is not the government of the day for the crimes of non-implementation, tardy implementation or partial implementation of the Thirteenth amendment. No! The target is precisely the Thirteenth amendment itself. This indicates that the Chief Minister seeks not the full implementation of the amendment but its supersession.

He goes on to criticise the office, role and function of the Governor, rather than the attitude and ideology of the present occupant of that post. He says “The Governor is the representative of the Executive President. No appointment is possible within the Province without the approval of the Governor. From the Secretary to the Minor Employees, it is the Governor who holds the whip hand.” It is only subsequent to this that he specifically criticizes the present governor.

Justice Wigneswaran then goes on to disclose the real reason behind contesting the Northern Provincial Council election. It was certainly not to make the 13th amendment work; still less to work constructively in the interstices of the present structure and situation so as to consolidate and proceed at a measured pace.

He poses and answers the question as to the TNA’s motivation. “At this stage someone might pose the question as to why we decided to contest the Provincial Council Election if the Thirteenth Amendment lacked teeth and was insufficient. There were two important reasons. Only if we stood for election could we bring out to the notice of the world the feelings and aspirations of the people of the Northern Province and show that the Government was portraying a false picture. In fact at the last Election the people were able to loudly proclaim their disapproval to the Government in power and the presence of the military in the Northern Province. Secondly without power, without authority in our hands to proclaim insufficiencies in the Thirteenth Amendment at Colloquiums and Seminars made no impact on the Government nor the International Community. But we felt it was better to get ourselves established in authority, experience the short comings in reality and thereafter tell the world what was happening. That exactly is what we are doing now. Rather than to merely say that Thirteenth Amendment is insufficient we feel exposing its shortcomings while established in office would be beneficial for future changes.”

Thus the objective of the TNA has not been to secure the full implementation of the 13th amendment and to expose the government for non-implementation, but rather to expose the insufficiency of the 13th amendment as such!

Justice Wigneswaran then moves seamlessly from the problems of devolution to the UN Human Rights Council resolutions, referring to “the objective of the 2012 UN Resolution”, thus revealing the nexus between external pressure and their strategy.

The next point is about the military in the North. The grievance is not the overly large footprint of the military. No, it is the very presence of the military in this most strategically sensitive of border areas for the Sri Lankan state that is seen as incompatible with reconciliation. He says “You cannot continue to keep the Military in the North and expect reconciliation and regeneration. The Joint Declaration by the President and the UN Secretary General in May 2009 has not been honored to say the least.” Thus he does not want the military kept in the North, in any configuration. His reference to the joint declaration between UN Secretary-General and the Sri Lankan President is irrelevant and misleading because there is absolutely no commitment to the non-retention of the military in the North.

The Chief Minister’s speech then escalates to its maximalist political climax. He says “It should be understood by all clearly that the present Provincial Council cannot be a vehicle of change for the betterment of the Tamil speaking people of the North and East.” This must be understood clearly by the diplomatic community for what it is: a structural rejection of the system of Provincial Councils itself. This rejection goes far beyond a criticism of the present government for its immobility. It is a rejection of the Indo-Lanka accord and its product the 13th amendment.

He follows it up with a programmatic political proposal of dangerous dimensions saying “It could be converted into a transitional Administration.” What exactly such a transitional administration would be transitional to, the Chief Minister fails to indicate. Therefore the goal remains open-ended. It would seem that the Chief Minister is picking up the infamous ISGA model of the LTTE.

The Chief Minister alleges that “for 65 years since Independence the problem of the Tamil speaking people of this country have not been solved”, which ignores the role of the LTTE and ‘great hero’ Prabhakaran in wrecking such efforts. Mr Wigneswaran alleges in all seriousness that “consecutive Governments of whichever hue were only interested in foisting more and more hardships and calumny on our people.” He thus dismisses every single Sri Lankan administration—all democratically elected, one might add—including, obviously, that of President Kumaratunga who proposed three political packages which went well beyond the 13th amendment, all of which were rejected by the Tigers as well as the precursor of the TNA, the TULF and its leader Mr Sambandan, at the time. One cannot help but wonder what he was doing while these consecutive governments were intent on “foisting more and more calumny and hardship” on the Tamil people.

Most incredibly yet utterly significantly, Justice Wigneswaran, the newly elected Chief Minister actually uses the ‘G’ word: “…activities of successive Governments in this Country have bordered on genocide if not genocide…” All this in his first Budget speech!

He then unveils the strategic conclusion: “It is essential that an International strategy is innovated to quickly ascertain the views of the Tamil speaking people presently still occupying their traditional home lands.” Plainly the Chief Minister is calling for a plebiscite, a referendum of the Tamil people in the North and East, by means of “an international strategy”. This is an exit strategy; a roadmap for secession.

The game-plan designed by the Diaspora hawks is clear: (a) launch mass agitation either in the run up to or the immediate aftermath of Geneva March 2014 (b) goad the army into a crackdown and Colombo into dissolution of the Provincial council (c) use Jayalalitha and Tamil Nadu to leverage the incoming BJP, which unlike the Congress is not emotionally invested in the 13th amendment and deeply affected by the LTTE’s assassination of Rajiv, to push qualitatively beyond it. The model is the creation of Kosovo through an “international strategy”. The secessionist strategists in the Tamil Diaspora are going for the grand-slam. They seem to have politically and ideologically infiltrated or influenced the TNA/NPC. It is a pity that the Northern PC and the new Chief Minister is exhausting southern goodwill and laying the foundations for an anti-provincial autonomy multi-partisan Southern consensus, by playing according to the Diaspora/Tamil Nadu script.