Editors note: Through Nelson Mandela International Day, the UN General Assembly resolution A/RES/64/13 of 2009 recognizes Nelson Mandela’s values and his dedication to the service of humanity, in the fields of conflict resolution, race relations, the promotion and protection of human rights, reconciliation, gender equality and the rights of children and other vulnerable groups, as well as the upliftment of poor and underdeveloped communities. It acknowledges his contribution to the struggle for democracy internationally and the promotion of a culture of peace throughout the world.

Mandela is 95 years old today.

###

I never met Nelson Mandela in person, but once listened to him live.

I watched him speak — in his characteristically thoughtful and cheerful manner – for a few minutes, and was mesmerized.

That was in October 1995 at the United Nations headquarters in New York. Over 150 heads of state and government had come to the world’s most cosmopolitan city to speak at a special session of the General Assembly to celebrate the UN’s Golden Jubilee.

Among them were Cuban President Fidel Castro, Palestine Liberation Organisation leader Yasser Arafat, and playwright turned Czech President, Vaclav Havel. Three woman leaders from South Asia added to the diversity.

But I was especially interested in the first black President of South Africa. Nelson Mandela, whose African National Congress (ANC) had won his country’s first multi-racial election only the year before, came dressed in a colourful batik shirt (known as ‘Madiba shirt’, named after Mandela’s Xhosa clan name).

Every leader was given five minutes at the famous podium. Mandela used his 300 seconds better than most others. I still remember how he rose above a single country, or single cause, to call for a better deal for the poor and downtrodden worldwide.

He said: “At the end of the Cold War, the poor had hoped that all humanity would earn a peace dividend, enabling this Organisation to address an expectation it was born to address. And they challenge us today to ensure their security not only in peace; but also in prosperity.”

That wasn’t the first time that Mandela spoke at UN headquarters. He made a longer, impassioned speech on 3 October 1994: his first and, as he noted, the first by a South African leader drawn from the country’s majority people.

“We must ensure that colour, race and gender become only a God-given gift to each one of us and not an indelible mark or attribute that accords a special status to any,” he said on that occasion. “We must work for the day when we, as South Africans, see one another and interact with one another as equal human beings and as part of one nation united, rather than torn asunder, by its diversity.”

Such lofty ideals are often sprinkled by spin doctors who ghost-write speeches for many heads of state. Except in Mandela’s case, they sounded sincere and credible. The man probably wrote most of his speeches himself.

Mandela was clearly an inspiring orator. But when it came to walking the talk, he had few parallels.

Distant Turmoil

Watching Mandela work magic with words in New York was a high point in my own little journey in his inspirational wake.

Growing up in Sri Lanka in the 1970s and 1980s, I occasionally read about this man called Mandela who, by then, was the world’s most celebrated political prisoner. In fact, he had been jailed before I was born, convicted in the infamous Rivonia Treason Trial of 1963-64.

Sentenced to life, he would spend the next 27 years behind bars, 18 of which were at the Robben Island prison, some 7km offshore of Cape Town.

South Africa at the time was known only for bad news: student uprisings, racial tensions sparking off frequent violence and random killings. Its white minority regime was globally condemned for racial segregation and discrimination policies of apartheid. The rulers were isolated, but remained defiant and dismissive of the world’s opinion. Wealth from Africa’s richest economy was used to bolster its image.

Separated by the vast Indian Ocean, South African politics seemed too far away: satellite TV and Internet had not yet connected us to the Global Village. Then, in late 1982, it suddenly crash-landed in our own news in the most unexpected manner.

That’s when the Sri Lanka Rebel Tour to South Africa happened. Sri Lanka had recently gained Test Cricket status, and played only five Test matches. In a clandestine operation, 14 top cricketers were offered lucrative offers to tour the country banned and excluded from international sports since 1970. They succumbed.

The rebel tour was one of many attempts by the minority regime to buy international legitimacy — or at least to undermine sanctions and embargoes. All participating Lankan players earned a 25-year ban.

When that controversy faded away, so did South African realities in our minds. We had plenty of our own troubles. A separatist war in the North and a violent youth insurrection in the South left no time for us to reflect on South Africa’s prolonged struggle for freedom and equality. In hindsight, we should have paid more attention.

Three months after the Berlin Wall fell, President F W De Klerk took courageous albeit rather belated steps to dismantle apartheid. By then, the pervasive machinery of racial segregation and blatant discrimination had lasted for half a century, blighting the lives of tens of millions.

The long awaited day arrived on 11 February 1990, when Mandela walked out of the Victor Verster prison in Paarl, 60 km outside Cape Town. Speaking at a public rally in Cape Town later that day, he called for a “fundamental restructuring of our political and economic systems to ensure that the inequalities of apartheid are addressed and our society thoroughly democratised”.

Addressing a highly volatile and anxious country, he invited white compatriots to join in shaping a new South Africa. Watching the momentous events live on satellite TV, the world held its breath.

He ended quoting his own words from the defence statement he’d made during his treason trail 27 years earlier: “I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons will live together in harmony with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for, and to see realised. But my Lord, if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

Madiba and Chandrika

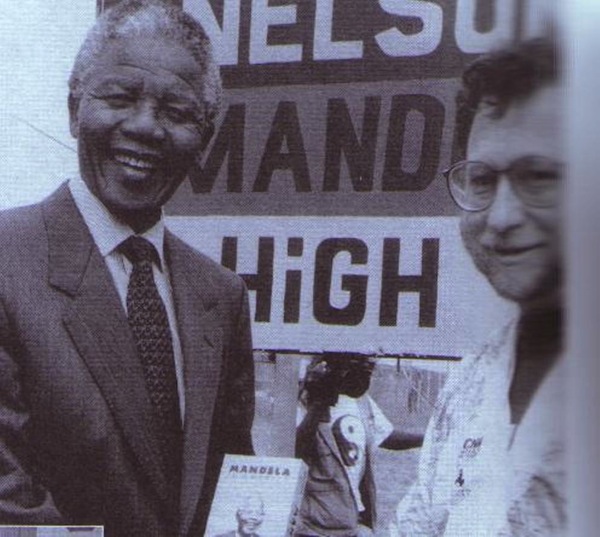

It was in the Fall of 1995 that I finally caught a glimpse of my hero. I was one of 20 journalists and broadcasters from as many developing countries, who spent three months covering the UN General Assembly in New York and studying how the organisation works.

My roommate in New York was Dante Konisa Tebogo Mashile, a producer from the South African Broadcasting Corporation, SABC. At 25, he was old enough to remember the dark days of apartheid, and excited to be part of the new Rainbow Nation. He was extremely proud of Madiba.

I’m more sceptical of politicians, but exceptionally at that time, I too had high hopes of my own head of state, President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga. Six months after Mandela became President, we Lankans had elected Chandrika with the largest ever electoral mandate (62% of votes) for a leader before — or since.

Like many others at the time, I expected Chandrika to usher in a more pluralistic, accountable and caring form of government. Little did we know that it would all be squandered after her first thousand days…

But that still lay in the future when Dante and I lined up hours to get through the intense UN security to listen to our respective leaders speak. On that chilly and windswept October morning in uptown Manhattan, we were two bright-eyed, idealistic young men fired by the audacity of hope.

The ‘Mandela Bug’

The other South African connection I made in New York was with the maverick US journalist Danny Schechter, a television producer and filmmaker whose video production company Globalvision hosted our journalist group for a day.

Danny was a ‘network refugee’— one among a handful of idealists who had left mainstream TV networks to pursue public interest journalism using alternative outlets (no mean task in those early days of the web.)

We listened in awe as he described his long and eventful career in advocacy journalism in support of human rights at home and abroad. He was equally scathing of successive US governments and much of the mainstream US media.

Danny had caught the ‘South Africa bug’ early on in his career, and also worked closely with many music industry stars in the Sun City Project that produced a hit anti-apartheid album in 1985-86. For three crucial years (1988 – 1991), he had produced South Africa Now, an independent weekly TV news programme that chronicled the last days of apartheid.

Danny told us how, in early February 1990, he was working on a one- hour documentary special for PBS titled Waiting for Mandela. They were 24 hours from broadcast when De Klerk made that historic announcement in Pretoria – turning their nearly finished programme upside down.

As he recalled later, “We went to work, re-editing, tapping into a South African broadcasting company feed, and setting up the first televised exchange between the ANC and a government that (still) refused to recognize the liberation movement.”

The hastily rehashed documentary, now renamed as Mandela: Free at Last, went out on PBS on schedule, offering depth and clarity to the breaking news moment. It was introduced as “the definitive primer on Nelson Mandela’s struggle against Apartheid, with rare footage, interviews with principal players, and the first speech Mandela gave upon his release from prison”.

In all, Danny has made six documentary films with and about Nelson Mandela, which he considers one of the great privileges of his life. (As he says, “I would rather do films about Mandela than Monica!”).

Rainbow Nation

Between Dante’s ground level insights and Danny’s socio-political context, I received an unusual kind of introduction to the complexities of South Africa. None of that makes me a specialist on the subject, yet it’s enough for me to marvel at what Mandela and his fellow freedom fighters accomplished — before and after apartheid was dismantled.

The Rainbow Nation had a troubled birth, and nearly two decades on, it’s still a work in progress. There are huge imperfections, and the reality falls short of aspirations. But without Mandela’s statesmanship, things could have been far worse.

During the past decade, I have had three glimpses of the Rainbow Nation in the making, with its many trials and tribulations.

My first visit was in mid 2002, when I went to Johannesburg as a journalist to cover the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD). At a BBC-PBS TV debate recorded at the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage site, I remember listening to the writer, political activist and Nobel Laureate Nadine Gordimer.

A conscientious white supporter of the ANC’s freedom struggle, she spoke passionately about unfinished business in social justice and equality. Later that day – at nearly 80 years – she marched the streets with hundreds of international activists calling for land rights for the poor. South African police watched from the sidelines.

Four months later, when in Cape Town to speak at a science communication conference, I wanted to visit Robben Island, now another World Heritage site with its own museum and tours. Alas, choppy seas and bad weather meant the ferry was cancelled.

So I had to wait almost a decade for Clint Eastwood to show me around Robben Island. His 2010 movie, Invictus, tells the true story of how statesman Mandela (convincingly played by Morgan Freeman) joined forces with the (white) captain of South Africa’s rugby team to help unite their divided country. The occasion was the 1995 Rugby World Cup hosted (and won) by South Africa.

The movie covers the first 18 months of the Mandela Presidency, and reminds us how perilously close post-apartheid South Africa came to anarchy and mayhem. When the transfer of power took place in May 1994, there was a tight window in which to pursue reconciliation after generations of acrimony. Mandela had the foresight, courage and capacity to balance the high expectations of his own people without alienating the economically influential whites.

Healing old and deep wounds of a brutalised nation takes time and effort. South Africans are still working on it, with government, civil society and even the private sector joining the process.

Truth and Reconciliation

Acknowledging the bitter past is an essential, cathartic part of such healing. The official Truth and Reconciliation Commission, headed by Desmond Tutu, the outspoken former Archbishop of Cape Town, set a high standard for a post conflict nation seeking to forgive without forgetting. The non-profit Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory now continues the mission of keeping memories alive – both as tribute, and as caution.

There are also independent efforts at rebuilding bridges between people. Returning to Johannesburg in mid 2011, I spent a day at a fine example: the Apartheid Museum.

The commercially owned facility is both an educational resource and a powerful reminder of how South Africa was a police state even a quarter century ago. Public signs such as ‘Natives and dogs not allowed’ were commonplace up to 1990.

As we enter the Museum, the ticket machine randomly assigns us a ‘racial identity’. In a simulation – probably the only one of its kind in modern South Africa – we must take the designated entrance depending on whether we are deemed black, white or coloured.

This ‘segregation’ lasts only for a minute or two, but sets the emotional context for the authentic and sensitively presented chronicle of one hundred years of South African history.

Some of the misery and struggle I had read about, but I didn’t know how much some intellectuals and professionals had justified racial segregation on all sorts of grounds. Evidently, opportunists are attracted to injustice in a maggot-like fashion — and not just in South Africa.

Preserving Memories

Sri Lanka’s conflict has had its own history and dynamics, which will continue to be analysed and interpreted in a myriad ways for years to come.

Beyond the deafening – and often exasperating – shrill, what are we doing to capture the memories of our own conflict before they naturally fade, or drown in a sea of denial?

How can we inspire more Lankan writers, filmmakers, photographers, journalists and researchers to rise above their own labels and politics to be custodians of our nation’s traumatic memories and bruised conscience?

And where are our own Desmond Tutus and Nadine Gordimers when we most need them?

The Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg unabashedly documents the horrors of apartheid, yet it ends on a note of optimism and hope. It is more than a reminder of a particularly dark episode in recent history. It also celebrates seven fundamental values, represented by seven pillars in the first courtyard: democracy, equality, reconciliation, diversity, responsibility, respect and freedom.

Mandela’s magic words once again capture the essence of it all: “For to be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.”

As Madiba nears the end of his own long walk, I have finally realized the futility of waiting for my own Mandela. There won’t be one, and there is no time to waste.

Each one of us must carry the flame ourselves — even if it’s only a candle in the wind.

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene likes being a fly on the wall in places where uncommon wisdom and courage is found.