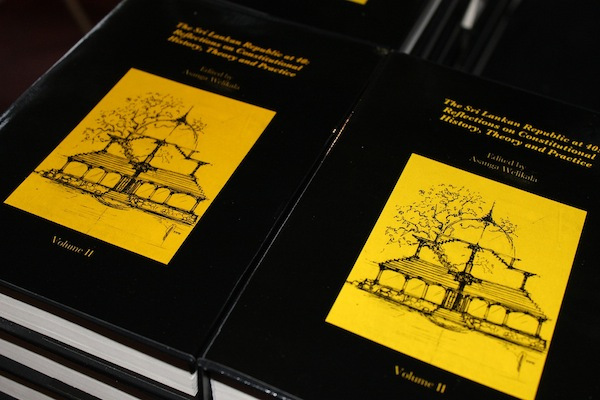

The Sri Lankan Republic at 40: Reflections on Constitutional History, Theory and Practice, edited by Asanga Welikala is an important contribution to the discussion on the problems concerning the republican constitutions of Sri Lanka and constitution-making projects and processes.

The volume contains three chapters dealing specifically with gender concerns in relation to Sri Lanka’s constitutional history which I subject to brief review here.

The chapter authored by Maithree Wickremesinghe and Chulani Kodikara deals with “Representation in Politics: Women and Gender in the Sri Lankan Republic”. The inadequacy of women’s representation in politics has been a vexed subject for Sri Lankan activists, advocates and feminists alike and has been written about fairly extensively. This chapter extends and nuances this discussion significantly, offering a timely exploration of political representation within the Sri Lankan republic vis-à-vis its women citizens and gender issues. It asks critically if the state has indeed represented the interests of women as a collective sex/gender; looks at the dominant political representation of women within the state, their exclusions and inclusions and the problems relating to such representation.

The chapter offers new insights to dispel a number of popular beliefs – among them that women enter or are compelled to enter the political arena primarily to strengthen family or party politics; and that women only enter politics at the death of a husband or relative relying on family connections. The authors argue instead that there is an often-ignored element of political persuasion behind such compulsion and that women do exercise agency in such decisions. It also points out that reliance on family connections is a phenomenon that holds true in the case of both males and females entering politics, as parties rely on these connections to garner votes where ‘nepotism is not only a customary political stipulation but has also become an acceptable political practice.’

Interesting discussions on women’s campaigning and strategising to increase political representation historically and in the current context and parliamentary debates on the issue underpin the analysis and critiques. This is a timely analysis that melds activism, advocacy and scholarship in an attempt to understand women’s citizenship and formal political engagement and representation in Sri Lanka today. Discussing the framing of constitutions – a central theme of the book – the authors note that the republican constitutions were inherently framed to promote Sinhala Buddhist interests and had no intent to protect citizenship and rights of any disadvantaged category including women. Thus the authors note that women have not been able to rely on the republican state to deliver on their rights in the face of other dominant identity interests and politics (especially when founded on religion and ethnicity).

This deep-seated flaw in the constitution is discussed in the context of the over-dependence on formal equality, which has failed to increase women’s representation in politics at either the national or the local level. The discussion is further extended to interrogate the refusal to accept identity and difference, and a rejection of any form of affirmative action in favour of women despite the rhetoric. In a comprehensive discussion of the sexual contract of the liberal democratic project, which privileges the male subject – conceptualising equality as sameness starting with the assumption of formal equality and not with the concept of difference – the authors note the insufficiency of this approach to deal with the question of the inclusion/exclusion of women in politics and in the exercise of their citizenship.

The chapter by Susan H. Williams discusses “Gender Equality in Constitutional Design: An Overview for Sri Lankan Drafters”. Her overview includes commentary on the structure of rights, looking at the distinction between positive and negative rights, and the distinction between the vertical and horizontal application of rights: both basic issues that have profound implications for the ability of women to use and enjoy their constitutional rights effectively, and goes on to interrogate the effect and desirability of limitation clauses. The author discusses extensively the over-dependence on formal equality in constitutions and its shortcomings, and makes a strong case for adopting a substantive model of equality in constitutions. Bringing in an important insight, the author notes that constitution drafters often limit their thinking on women’s equality to rights provisions and moves on to consider many of the structural aspects of a constitution that can have critical impact on the realisation of gender equality. In this context she discusses structural provisions such as electoral systems and quotas to increase women’s representation, and decentralisation that can enhance and enable gender equality. As importantly, she notes that there is an opportunity to promote gender equality in the section of the constitution that addresses the legislative process. Also discussed are provisions concerning the executive and provisions concerning the status of religious or customary law – here the author notes that the harmonisation of customary/religious law and gender equality is a delicate and important issue in many countries and a timely consideration for Sri Lanka. An interesting commentary is also made on the role of international law, making a call for the constitution to provide for a mechanism for women to use powerful international legal instruments such as CEDAW effectively in the domestic arena. In an important endeavour to assist future constitution drafting, the chapter reviews the Sri Lankan constitutions of 1972 and 1978 in terms of these issues.

Finally the author goes beyond review to warn that constitutions are often drafted by men who assume that the interests of women are similar to that of men. Therefore the author calls for serious consideration of the ways different constitutional choices affect women and makes a fervent case for taking women’s interests and perspectives seriously in every aspect of constitutional design and at every stage of the process. In a perceptive proposition, she calls for ‘fully internalising the simple but shocking idea that the constitution should be as much the product of women’s concerns and perspectives as men’s.’ This idea, she notes, will revolutionise everything about constitution design and drafting and enable the equal citizenship of women.

Ambika Satkunanathan writes a refreshingly different chapter in style and approach on “Whose Nation? Power, Agency, Gender and Tamil Nationalism”. The discussion is placed in the context of post-war Sri Lanka, but looks at narratives, personal journeys, reflections, strategising and activism of Tamil women who engaged with Tamil nationalism in its formative years post-independence, to those within the armed movements, and to those who chose to challenge Tamil nationalism from outside and create alternative forms of engagement.

The uniqueness and importance of the chapter is in its new empirical evidence that seeks to ‘nuance and problematise existing scholarship on women and Tamil nationalism.’ It asks if the ‘reproduction of norms in the course of women’s participation result in re-making gendered reality along new lines…Were women able to exercise agency even within very restrictive contexts, and thereby shape and even challenge the Tamil nationalist struggle?’ It thus looks at the ‘domestic sphere as a site of political resistance’ over the years of the multi-faceted Tamil nationalist struggle, arguing that women who engaged in political activism within party structures ‘unwittingly transgressed and thereby challenged traditional norms and restrictions’ on their agency, an historic legacy that allowed latter day Tamil women to leverage engagement within the militant movements. Despite this, Tamil woman remained ‘largely invisible within Tamil party politics’ even when they were active in the public sphere, and the author goes on to critique the historical inability of Tamil political parties to acknowledge women’s concerns and provide space for their political participation, a situation that continues to date.

Another interesting proposition made by the author is that the LTTE’s puritanical rules on sexual behaviour were used ‘to create an environment which was conducive for the participation of women; an environment that would be acceptable to conservative Tamil society.’

However, with the end of the war, Tamil women combatants are impaled on the horns of a dilemma. Through a set of poignant vignettes the author records the narrations of former women combatants who trace their agency within the LTTE and their current conundrum of having to deal with the securitised state that continues to perceive them as the enemy ‘other,’ and a resurging conservatism within Tamil society that also seeks to erase them from history for the very ‘transgressions’ they were once valorised. The author suggests that this is to be expected in a community that sees themselves under siege, and makes a strong case for recording ‘Tamil women’s civic and political activism in the past to mobilise women to become active participants in social change’ in the present.