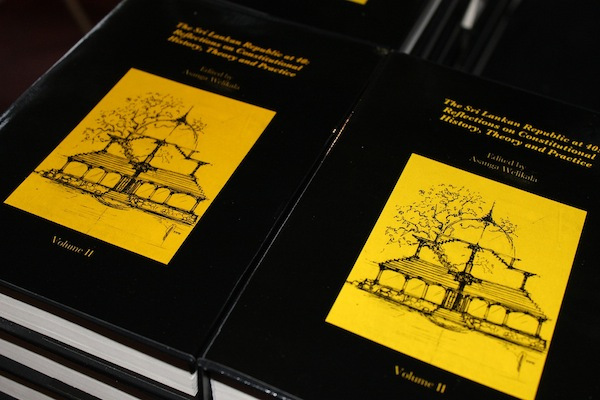

Coming as it did at the end of 2012, The Sri Lankan Republic at 40: Reflections on Constitutional History, Theory and Practice, is much more than two edited volumes or an extensive anthology. Rather, on close reading it seems more a living embodiment of current and critical debate at the very heart of the Sri Lankan body politic. Here are voices and perspectives from the fields of law, politics, sociology, history, gender and religion (to name a few) that speak to the reader and to each other on both the history and the power of the constitution. It navigates through the past – charting ‘the course from the liberal democratic post-colonial constitutional inheritance to the promulgation of the republic as part of the nation- and state building project’ [i]. Because the volumes give voice to scholarly and political views through specialist thematic writing and interviews, we also get a wide picture of experience and diverse viewpoints. All of the authors deserve credit and congratulations for the quality of scholarship and presentation. This review will only manage to name some of them, but holds all contributors in respect for their work.

Republic at 40 is comprised of two volumes running to 1166 pages and organised through four sections: (1) constitutional history; (2) constitutional theory; (3) constitutional practice; and (4) interviews and recollections. The parameters of these headings are broad. This results in no less than twenty-two scholarly chapters (at times frustratingly profound but also exhilaratingly insightful) and five in-depth interviews. They can be read sequentially or dipped into according to interest and elected cross-referencing. For the external observer, it is a doorway to comprehension of that which too often appears incomprehensible; the seeming dismantling of an island democracy and resurgent religious/ideological militancy that verges on ‘self-destruct’ mode. Herein emerge key historical and detailed background on the origins of the centralised unitary state; populist majoritarianism, Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism and Tamil identity/nationalism in turn, with all the ramifications of disenfranchisement and a long and bloody war. The constitutional origins are traced for fundamental rights, the growth of executive power, the use of parliamentary select committees; and judicial review – used so recently as counter force to directives including the ‘Divineguma’ bill and the impeachment of the Chief Justice and the installation of a named successor.

Today the term ‘republic’ most generally means a system of government which derives its power from the people rather than from other foundations such as heredity or divine right. “It is impossible to establish a perpetual republic,” wrote Niccoló Machiavelli in The Discourses (1517), “because in a thousand unforeseen ways its ruin may be accomplished.” Machiavelli explains at the start of the third book of The Discourses that all worldly things have a limit to their life, and that “in the process of time [a state’s] goodness is corrupted, [and] unless something intervenes to lead it back to the mark, it of necessity kills that body. [ii] This occurs because after ten years at most men begin to corrupt, to behave with greater danger and more tumult, to transgress the laws, and to do so in a manner that makes it unsafe to punish them.” The return to the beginnings of a republic comes either by extrinsic accident or internal prudence, and the preferred Machiavellian option ought to be clear: “either good orders or good men must produce the effect” (Discourses III.1.1-6, pp.209-12).

If the legal sources in these volumes may be traced to colonial and pre-independence precedent and influence, its coverage of history nonetheless does credit to the unique and wider Sri Lankan experience and context. In his chapter ‘Republican Constitutionalism and Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalism in Sri Lanka: Towards an Ontological Account of the Sri Lankan State’, Roshan De Silva Wijeyeratne offers an account of pre-colonial influences in his exploration of ritual, belief and the ordering principles of Buddhist kingship as depicted in the Pali chronicles. While these volumes are dedicated to a subject aged forty years, it is clear that there are earlier and influential incarnations of the body politic which are brought to bear on the republic.

Udaya Gammanpila goes further in his volume-two interview, ‘The Constitutional Form of the First Republic: The Sinhala-Buddhist Perspective’ on the role of Buddhism including the ancient precedent of threefold governance; the King, the people and the Buddhist monks. On page 903 we read how distinctly the remembered model differed from Western practice: “In Western societies, the king was considered as a person who got a mandate from the almighty god to rule the country. He was supreme, very powerful and very sacred as well.” But according to the Anguttara Nikaya (he continues) the king is only the custodian and not an almighty ruler. “He has to look after the people, on behalf of the people.” From this perspective, ‘Maha Sammatha Vaadaya’ was a better approach than Western democracy, and given the history of colonial electoral laws and Sri Lankan constitutional development, Articles 9, 10 and 14 (1) (e) of the present constitution (1978) are sufficient as ‘minority-friendly’ clauses.

This particular argued case for the historical, cultural and legal accommodation of diversity is followed by the next interview, ‘The Ilankai Thamil Arusu Katchi (Federal Party) and the Post-Independence Politics of Ethnic Pluralism: Tamil Nationalism Before and After the Republic’ with R. Sampanthan. The discussion with Sampanthan offers an overview which extends from the history of the ‘fifty-fifty’ platform before the Soulbury Commission, the founding of the Federal Party and the importance of all peoples; how ‘Tamil- speaking’ as a term was inclusive of Hindus, Muslims, Christians and others as well as historical examples of jurisdiction and administration; the Thirteenth Amendment and the question of democratic rights in the absence of independent institutions. Here, alongside the other interviewees including D. Sithadthan, P.P. Devaraj and Lionel Bopage is living history and the crux of on-going concern and debate.

Bopage addresses the Sri Lankan transition from the colonial to the neo-colonial and the structural difficulties inherent in political or economic ‘independence.’ Here is a critique of both the specific Sri Lankan path to capitalism but also of the Provincial Council system from a Marxist, Leninist (with homage to Luxemburg) perspective. Here also is a closing thought that dialogue is possible to ensure the aspirations of marginalised peoples are fulfilled. A brief review such as this cannot to justice to all the expression and detail captured on these pages.

Re-examining History

And so back to the beginning of the first volume. Part I is on constitutional history, with a vivid and detailed start from Dr Nihal Jayawickrama who was himself an official participant in the 1970-72 process. Of particular interest is the first-hand account of the drafting process and degrees of participation, along with reproduced primary source material in the forms of letters and exchanges relating to provisions on concentration of power (notably the National State Assembly), the role of judicial review and the need for inclusion of fundamental rights and freedoms. He concludes with useful lessons on process and form in constitution-building. Radhika Coomaraswamy points to the crippling of the judiciary in 1972, the enshrining of the Buddhist faith as a state religion through an affirmative duty to protect and cultivate it; and dynamics concerning the Soulbury Constitution. Many held that a powerful executive would break free from the past and have the autonomy for implementing the radical reforms worthy of the new Sri Lanka. And yet here also were sown the seeds for authoritarianism.

Power-sharing was a contested area in preparations for independence from British rule, then dealt with (after extensive investigation and debate) by Section 29 of the Soulbury Constitution. At the time of independence as a dominion in 1948 Section 29, authored by Sir Ivor Jennings provided for the power of Parliament to make laws for the peace, order and good government of the island, while stipulating that: (2) No such law shall: (a) prohibit or restrict the free exercise of any religion; or (b) make persons of any community or religion liable to disabilities or restrictions to which persons of other communities or religions are not made liable; or (c) confer on persons of any community or religion any privilege or advantage which is not conferred on persons of other communities or religions; or (d) alter the constitution of any religious body except with the consent of the governing of that body. Provided that, in any case where a religious body is incorporated by law, no such alteration shall be made except at the request of the governing authority of that body. (3) Any law made in contravention of subsection (2) of this section shall, to the extent of such contravention, be void.’ Under this constitution, minorities of Ceylon had recourse to the courts and finally to the Privy Council should their rights under the covenant be violated. The Privy Council and the Crown were thus the guardians of the covenant between the Tamil and Sinhala communities.

Asanga Welikala begins his chapter with the United Front landslide victory in the general election of May 1970. The UF manifesto sought a mandate to repeal and replace the Soulbury Constitution with a new and republican one. At stake was a new entity, a free, sovereign and independent republic pledged to realise the objectives of a socialist democracy, also securing fundamental rights and freedoms for all citizens. According to Welikala, even at the time there were differing schools of thought regarding Section 29 in its procedural and substantive import. He takes us back to the rising expectations and political turmoil of wartime Asia, the context of the earlier Declaration of 1943. The Ceylon Ministers’ draft constitution was prepared for submission to the British government in the following year, with two major provisions for the protection of minorities. One was weighted electoral provision concerning parliamentary seats for the Northern and Eastern Provinces; secondly there would be constitutional prohibitions on discriminatory legislation.

We are reminded of the prevailing mood in the decolonising world – the anti-imperial nationalism and ‘complete break with all colonial institutions and appurtenances.’ Defiance and independent action as the mood of the day lent itself to a ‘naked majoritarianism’ in the making, such that the birthing of the republic also ‘was in this sense the first historical instance and demonstration of the dangers presented by populist majoritarianism to the constitutional state’ that continues to haunt Sri Lankan political and constitutional culture. And yet the drafting of the Soulbury Constitution and subsequent transfer of power went forward smoothly, without the broader popular elements of nation-building. There was no mass independence movement, no popular uprising but rather a gentlemanly agreement between elites. Furthermore, it is argued that through the technical application of ‘seemingly apolitical’ rules of legal interpretation and procedural limitations, Section 29 proved ineffective when discriminatory measures were brought in. Hence the Sinhala Only Act and reaction to it, leading to widespread protest, communal rioting and the 1958 declaration of a state of emergency. The die was cast. Through a thorough examination of Jennings’ intent and ‘manner and form’ entrenchment, as well as detailed case law and precedent, this chapter charts both autochthony and the birthing of political institutions free of constitutional control.

Benjamin Schonthal examines the Buddhist Chapter, Section 6, of the republic’s 1972 legal charter, debates, drafts and assurances. Farzana Haniffa examines the Muslims and the constitution-making process of 1970-72, with a thoughtful exploration of divided societies and governance models. She both appreciates history and articulates the multiplicity of experience of being a minority in Sri Lanka, also examining Muslim politics in the post-colonial era. Her quote from A.C.S. Hameed (MP for Akurana) of the UNP, making a representation in the Constituent Assembly, is moving: “A constitution is not written for a generation. A constitution is written for generations to come. And if a constitution is to last in the context of a South Asia country like ours, where people of various races, religions and cultures inhabit, the constitution must serve as an instrument unifying the various peoples into one – equal to one another, in no way subordinate to one another. A unified nation blended into one people breathing the air of freedom. It is with this sense of dedication that we support this motion before this assembly” (p. 243). Given the historical experience and geographical dispersal of the Muslim population, notions of pluralism resonated more than those of federalism at the birth of the republic. The persistent experience of being in the middle between adversaries, of being on the receiving end of their own expulsion and experience of riots or massacre has altered views of participation in and expectations of the state. Haniffa’s closing lines depict contemporary entrenchment of the marginalisation of minority claims.

Michael Roberts addresses the period 1231-1818, the ‘middle period’ as he calls it ‘in order to escape from European periodisation.’ His source material is rich, drawing from the literary and the epic to trace development of what is often called politicised Buddhism. His data supports the picture of cakravarti figures vested with super-human qualities, devotional and martial followers dedicated to defending valued territory. Hierarchy and kingship were crucial in defence against the Portuguese, the Dutch, the French and the English. ‘Us and Them’ cleavages in the worldview could not but be exacerbated by Western scholarship as it flowed into the equation with distinctions of Aryan and Dravidian language, or beliefs on social difference which verged on racist or certainly classist, thus underlining caste division or negative views of mixed marriage and ancestry lines. “The part-is-whole equation in the relationship between the categories ‘Sinhala’ and ‘Lanka’ has been one of the critical issues of the contemporary era.”

Then at the end of the first volume, a quiet yet riveting exploration of nested levels of agency, self-realisation and political struggle unfolds in the writing of Ambika Satkunanathan. ‘Whose Nation? Power, Agency, Gender and Tamil Nationalism’ is a chapter which challenges dominant narratives, explains gender and power issues which are not always visible, and holds up a giant mirror for readers. In these reflections we cannot but contemplate the difficulties of national projects; the distance from political declaration to personal life and from aspiration to realisation. It begins with the poem ‘Our Liberation’ by Sivaramani:

What shall we gain comrades?

What shall we gain?

We stand having lost all joy and youth

We come burdened with

Trepidation and poverty

What shall we gain?

You called it liberation

You called it independence

You said it was our race

You said it was our soil

Countries have been liberated

and gained independence

Nevertheless in many countries

the people have been beggared

Comrades will be also be

beggared when we achieve our

liberation tomorrow?

We have lost everything

However, we do not want

freedom only for a few

We do not want freedom with shackles

We shall achieve liberation only

after we shackle the animals

amongst ourselves

The analysis and wisdom in this chapter surpass its specific focus. Nation-building can bring women to the political sphere (as constitutions mention them and make declarations in their favour) but the boundaries between political and private blur amid embedded patriarchal norms and expectations. For the sphere of the republic at forty, how will women be encouraged to participate in politics given the vested interests in play, and obstacles to both participation and dissent? Satkunanathan refers to the current situation in the North, where talk of cultural decimation and the need to protect Tamil tradition is increasingly heard since the end of the war. “The resurgence of conservatism is to be expected in a community where traditional social networks and social norms have broken down and there is a general feeling the community is under siege” (p.659). The need and agenda for political rights overshadows women’s empowerment and rights. Alternative spaces are created and re-created in sites of struggle.

On Constitutional Theory

Sir Ivor Jennings and Section 29(2) appear again in these pages notably in the chapter co-authored by Cheryl Saunders and Anna Dziedzic, which gives a comparative perspective on parliamentary sovereignty and written constitutions. Here we find in full the doctrinal quandary regarding Section 29(4) on the legislative power of constitutional amendment, is this in itself the power to alter the constitution of which it is a part? The two authors concur with the view of Jayawickrama that the institution which assumed the authority to draft and adopt the new constitution also benefitted from it, a confirmation of Elster’s theory on institutional self-interest in constitution making. “The Constitution of 1972 reflected the interests and preferences of the current parliamentary majority. It would not survive the next change of government in 1977” (p.501).

Kumar David expands our theoretical horizons through revisiting The Communist Manifesto and dialectical materialism, reminding us of capital and accumulation, reproduction and production, class struggle and class relations. In identifying the relationship between the pursuit of socialism and the relative autonomy of the bourgeois democratic state, he highlights ideological challenge and practical confrontation. The capitalist economy will undermine the democratic state, through cycles of action and reaction as exemplified in Thatcher’s onslaught against the welfare state. He offers an ‘inside-outside’ view taking global changes into account, noting the relentless rise of neo-liberalism and steady erosion of the power of the old left.

An ontological account is offered by Roshan De Silva Wijeyeratne, who takes both republican constitutionalism and Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalism as his study, beginning with two enticing quotations: “…history begins with a culture already there’ from Marshall Sahlins, Culture and Practical Reason, and ‘..human beings must create the social and political realities on which their existence depends’ from Bruce Kapferer, The Feast of the Sorcerer. He acknowledges the extraordinary resurgence in Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalism both as official narrative and within society since the end of the war. Given the consolidating by the state of the monopoly of force and the (in his words) existential encompassment of the Tamil people, there is little sign of constitutional reform long deliberated by liberal constitutionalists. Wijeyeratne is eloquent in his revisiting of the past and in particular the defining moment in 1972 in its revolutionary sense. The 1972 Constitution is replete with the particular cultural inheritance of Sinhalese nationalism which may be reimagined so as to distinguish underlying cosmological metaphors. This shift in analysis leads to a realisation that Tamil political rhetoric is dealt with through the means of demonisation at a deep level, possibly in a reinterpretation of ingrained ritual and worldview.

Through an examination of colonial and post-colonial modernity this chapter sets out more recent history in altered perspective. The emotive ‘restoration’ of the Buddhist state which has been invoked and popularised is open to question if the imagined Sinhalese centralised state which has existed since time immemorial is intrinsically a product of British colonial bureaucratic order from the 19th century. But emotion and belief combine for mobilisation with violent consequences. Here is a theoretical contribution which offers a new understanding of the violence and darker side of repression and accumulation.

Constitutional Practice

The 1972 Constitution made a total break with the British Crown; Section 1 declaring a free, sovereign and independent republic. With it came Section 2 and the declaration of the unitary state meaning that from inception there would be problems with introducing any idea of semi-federal reform (Arulpragasam, chapter 18). There were improvements on the Soulbury Constitution including the section on ‘fundamental right and freedoms’ but previous safeguards on minority rights were repealed and not replaced. Both documents and frameworks had assumed the winner-take-all Westminster-type parliamentary model. This would change in 1978, and the rest, as they say, is history but also just yesterday and today and we must seriously also consider tomorrow. Arulpragasam contextualises with no less than twenty-three discussion points the historical evolution of democracy versus realpolitik in Europe and elsewhere; the problems of pluri-nations, imperial ventures, winners and losers. And this is just one chapter (p. 734).

The prevailing notion and critical problem of fundamental rights are further explored by Jayampathy Wickramaratne, who sets out precedents from the 1947 (Soulbury) Constitution for prevention of discrimination on the basis of race or religion, citing Section 29(2) (as above) which protected the free exercise of any religion and respect/non-interference with governing bodies of religious entities incorporated by law with Section 29 (3) stating that any law in contravention would be void. Here too an account of how the efficacy of written intent was tested by the circuitous practice used to disenfranchise hundreds of thousands of Indian Tamils who had voted in the 1947 general election (as British subjects) through the legal and technical re-definition of citizenship. Through Supreme Court and Privy Court, all was proper and correct, further paving the way for the Official Language Act of 1956.

Yash Ghai writes on ‘Ethnicity, Nationalism and Pluralism’ drawing from his extensive expertise and noting the attacks and strains in recent years on the liberal state. He outlines recent Kenyan experience with a cautiously positive note in light of the changes incorporated through the new 2010 constitution. A seasoned and respected expert who took popular consultations on the new constitution to village level, Ghai is clear on the obstacles. He reminds us that a constitution cannot guarantee its own effectiveness, naming characteristics of those in power in this case: “They will do everything in their capacity to sabotage implementation. They control not only the State, but also key sectors in society: through bribery, commercial and financial empires, manipulation of ethnicity, intimidation, armed force, and more” (p.699). But herein also lies something unique for the future of Kenya, for he states significantly that the people seem to regard the constitution as their friend. Ultimately it may be this sense of ownership and determination to protect it that makes a difference.

The chapter by Nicholas Haysom on ‘Nation Building and Constitution Making in Divided Societies’ gives an overview and offers both hope and direction. While recognising restructuring in the international system and the number of racist or xenophobic incidents in Western democracies, there is also evidence that the integrating approach of the liberal democratic model has been successful in providing civil rights and opportunities to cultural minorities. Haysom identifies conditions for success: enforceable rights in a legal system that respects the rule of law; conditions of economic opportunity that allow individual upward mobility regardless of group identity (even if more in perception than reality); absence of discrimination or at least a level of cultural and religious tolerance; a national identity that allows entry to members of culturally diverse groups; and the practice of interest-based politics (p.877).

Two chapters look particularly at gender issues and constitutionalism in Sri Lankan context, one jointly written by Maithree Wickramasinghe and Chulani Kodikara and the other by Susan H. Williams. The first provides an account of women’s representation, precedents in leadership and generally low levels in women’s representation in Parliament, provincial councils and local government institutions. Useful reference is made to CEDAW and the challenges in mainstreaming gender equality. Williams expands on the vertical and horizontal application of rights, possible mechanisms and remedies. Her examination of open list proportional representation systems indicates that this approach often undermines any quota system as the rearranged order of party lists means that women are moved further down.

It was the 1978 Constitution which moved to PR and it is worth noting here that among the negative outcomes has been the weakening of the relationship between the MP and the voter. This is due to the fact that MPs no longer represent a specific electorate, but are elected to an electoral district which may contain a number of traditional electorates. It can also be argued that because candidates are now compelled to campaign throughout an electoral district with a number of traditional electorates, election campaigns under PR system have become more costly. This leads to two unintended negative consequences: candidates with the wealth and means to finance expensive campaigns have a better chance of winning; and there is more of a likelihood that they may turn to or depend on benefactors/ rich businessmen thereby making corruption an integral dimension of electioneering.

Apart from the fact that PR is often viewed outside Sri Lanka as a panacea for the shortcomings of ‘first past the post’ systems, it is important to note electoral processes in relation to the republic. The 1978 Constitution did not specifically affirm the principle of parliamentary sovereignty in the same manner as the 1972 version, but nonetheless ‘seemed implicitly to perpetrate some of the theoretical assumptions about the ultimate supremacy of Parliament” [iii]. It follows that structural constraints on election itself and how Parliament functions will play into the hands of a strong executive. Further strains will be observed in the efficacy of parliamentary select committees.

In the interview with PP Devaraj the question is asked ‘What constitutional changes need to take place to protect the interests of the Indian Tamil community?’ (Previous to the question, Devaraj also refers to the role of the Soulbury Commission in relation to the Delimitation Commission and demarcation of electorates so as to be representative of castes as well as ethnic minorities.) His reply on constitutional change is clear. First of all a constitution must refer to the component groups which constitute the country – and there is a formula as stated by the APRC Final Report, Article 1 (4); that “The People of Sri Lanka is composed of the Sinhala, Sri Lankan Tamil, Muslim, Indian Tamil, Malay, Burgher and other constituent peoples of Sri Lanka. The right of every constituent people to develop its own language, to develop and promote its culture and to preserve its history and the right to its due share of state power including the right to due representation in institutions of government shall be recognised while strengthening the common Sri Lankan identity. This shall not in any way be construed as authorising or encouraging any action which would dismember or impair, totally or in part, the territorial integrity of political unity of the Republic” (quoted on p.998). Readers will recall that the Final Report of the APRC submitted to the President in 2010 was never made public. Rather a version was published by two committee members and made available by Groundviews.

It is fitting that this text, with all its potential is cited towards the end of the second volume; that the work of the APRC group so tasked managed to reach a public audience regardless of being rendered officially invisible. For the thread running through the Republic at 40 volumes is not only the rise of a type of aggressive majoritarianism but also the quest for legitimacy in democratic forms and processes. We may ask about the gap between constitutional history, theory and practice and the wider public in Sri Lanka. What is known of the constitution or understood in the wider public domain now that the republic is forty? In life span this is not so old. What process would be needed for meaningful ownership and ‘buy-in’ to constitutional values and principles for a national project of inclusion and belonging? For inclusion and belonging with respect are so different to doctrines of sameness and domination. The publication is testimony to informed alternatives.

As a historical study and platform for discourse The Sri Lankan Republic at 40: Reflections on Constitutional History, Theory and Practice is a substantial contribution, hopefully to be circulated to libraries and made available for study. It is a massive work, with some 123 pages of bibliography to the end. There appears to be numbering repetition in the final volume (with two chapter 23s) but any reader can sympathise with the state a proof reader might be in by that time. An index would be useful for the student or researcher – perhaps for the second edition some volunteers would come forward to help compile one. But all in all, a sterling achievement.

###

[i] From the Preface, by Dr. Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu, p.28

[ii] See ‘ Necessity as virtue in the thought of Machiavelli’ by Z.J. Witlich, available at: http://ase.tufts.edu/polsci/studentresearch/Necessity.pdf

[iii] See Niran Anketell and Asanga Welikala, ‘A Systemic Crisis in Context: the Impeachment of the Chief Justice, the Independence of the Judiciary and the Rule of Law in Sri Lanka’, Centre for Policy Alternatives Policy Brief April 2013, p.23