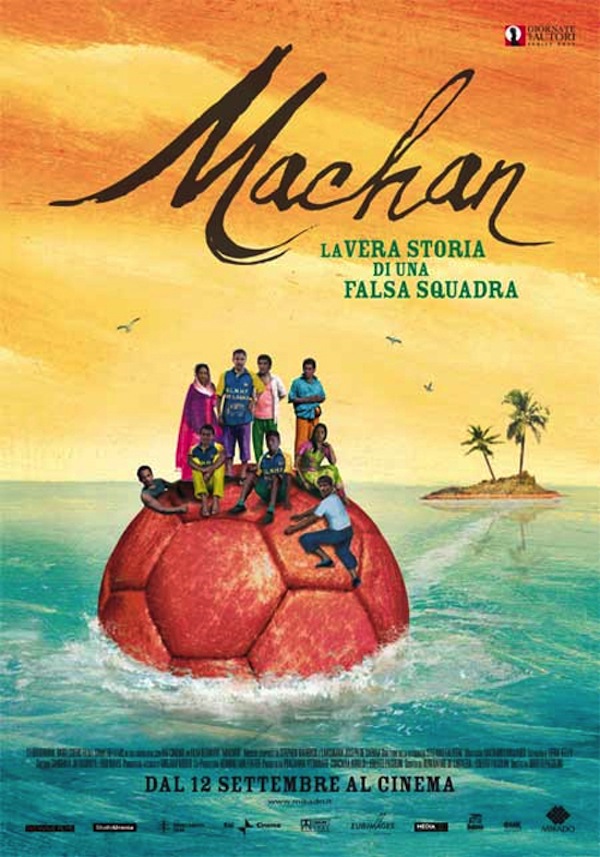

The opening scene in the German-Sri Lanka feature film Machan (2008) unfolds at a garbage-strewn Colombo street, somewhere in the city’s underbelly. Three young men are putting up political posters, playing hide and seek with policemen on night patrol.

Conversation reveals that the men are doing this to earn a few rupees. Soon, the inevitable question comes up. “Why don’t we get the hell out of this country?” asks one.

The ‘patriotic’ one replies, “Nothing like Sri Lanka. Abroad they treat you like second class citizens.”

At which point, lead character Stanley points to himself – his dirty clothes dripping wet in sweat, paappa (paste) and dog urine — and says, “So what are we now? First class?”

That, to me, was the most revealing moment in the perceptive film, ostensibly a comedy. An able-bodied young man, clearly willing to work hard, sees no hope of doing well in his own country.

The rest of the story revolves around a fake Lankan handball team going to Germany to play in a tournament. Every member of the team – players, manager and coach – soon goes missing. They scatter in integrated Europe, looking for greener pastures.

Italian director Uberto Pasolini based the film on a true incident that happened in 2004. Before and since, thousands of young men and women have been leaving their land — by hook or crook – for completely strange lands.

For three decades, such action was attributed to the long-drawn Lankan civil war. That certainly was one reason, but not the only one.

It doesn’t explain why, three and a half years after the war ended, the exodus continues. Every month, hordes of unskilled, semi-skilled and professionally qualified Lankans depart. Some risk life and limb and break the law in their haste.

It isn’t reckless adventurism or foolhardiness that sustains large scale human smuggling. That illicit trade caters to a massive demand.

Most people chasing their dreams on rickety old fishing boats are not criminals or terrorists, as some government officials contend. Nor are they ‘traitors’ or ‘ingrates’ as labelled by sections of our media.

These sons and daughters of the land are scrambling to get out because they have lost hope of achieving a better tomorrow in their own country.

I call it the Deficit of Hope. A nation ignores this gap at its peril.

Mind the Gap!

There are other formidable gaps. The government is preoccupied with bridging the burgeoning budget deficit, and also balancing imports and exports. Social and political activists, meanwhile, are busy protesting the growing democracy deficit.

These are all important and urgent. But who can take up the ‘silent emergency’ of young Lankans progressively losing hope?

Both anecdotal and statistical evidence indicates a pervasive trend.

A global comparison of net migration rates shows Sri Lanka having a minus 1.95 score in 2012. That is the difference between the number of persons entering and leaving a country during the year, per 1,000 persons (based on midyear population). In the SAARC region, only Pakistan, Afghanistan and the Maldives have a bigger negative score.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not opposed to migration per se. Humans and their ancestors have been moving around this planet for at least 100,000 years, creating a delightful melting pot of races and cultures. Nation states trying to guard borders against new arrivals is a relatively recent phenomenon, and not always an effective one.

And unlike certain countries with restrictive emigration policies, Sri Lanka allows its citizens to freely leave the country (as long as they do so through official channels). This wasn’t always the case: until 1977, Lankans travelling overseas – even for private reasons and using their own money – needed ‘clearance’ from a government babu.

All I’m questioning is this: why is there a widespread sense of hopelessness among many Lankans about pursuing their personal dreams in their own country? Are their ambitions and aspirations too lofty for our society and economy to support?

The desire to leave is most discernible among young people. A national youth survey in 2010, conducted for the Ministry of Youth by sociologists at the Colombo University, found that as many as 50 per cent of Lankan youth “wanted to migrate”. The survey covered a large, distributed sample: 3,000 randomly selected youth between 15 to 29 years, in 22 districts excepting Kilinochchi, Mannar and Mullaitivu.

The reasons for going overseas are many and complex — the best of surveys can only capture a part of what people really think or feel. But surely something is seriously wrong when half the country’s young people want to exit?

Personal circumstances shape each individual’s tough decision to leave behind loved ones, peers and familiar settings. Bread and butter considerations rank high: chances of doing well professionally or starting one’s own family.

What does a young man or woman entering the work force – after 15 or more years of studying and training – confront today?

The good news is that the guns are silent, car bombs are not going off any more, and roads and bridges are being built in earnest.

But securing a decent job on merit and talent has become more difficult. Being self employed or starting a small business is hard when banks don’t lend easily.

Without parental wealth, old school ties or political connections, a qualified youth finds it really tough to get a break, let alone succeed. A generation ago, the underdog still had a sporting chance.

What Meritocracy?

The cocktail circuit never tires of lamenting what is wrong in the country. Our political and business leaders, meanwhile, keep urging youth to be honest, hard working and entrepreneurial. But how many movers and shakers have created an enabling and nurturing environment for that to happen?

And are our academics and processionals – most of them beneficiaries of free education and meritocracy – doing enough to safeguard these core values? Clamouring for 6% of GDP for quality education loses meaning when the ‘products’ of that process are abandoned en masse in the end.

In a rare moment of candour, an engineer who hails from the grassroots and reached the heights of academe told me: “I’m all for egalitarianism and meritocracy – until I become part of the elite!”

No, forced equality a la socialism is not the answer. Life is inherently unfair, and everyone needs plenty of resolve and resilience for the bumpy ride. But when feudalism is endemic, and favouritism rules the day, some idealistic young people may decide…enough is enough.

For evidence, browse the Lankan blogosphere – the digital graffiti of a disenchanted generation.

Perceptions Matter

When someone is debating hard whether or not to stay on, the larger societal context also plays a part.

Most Lankans cherish three institutions, holding them practically sacred: universal adult franchise (symbolized by elections), free education (competitive public exams) and the de facto national game of cricket. In recent years, irregularities and malpractices have corroded the integrity of all three.

Rigged elections, leaked exam papers and match fixing have become the norm. True, there still are some honest public servants, conscientious judges and courageous newspaper editors. But they are outnumbered and, for the most part, voices in the wilderness.

Just ask Kumar Sangakkara. Or Victor Ivan.

Perceptions matter a great deal in private decisions. Most human decisions are not ruled by macroeconomic data or legal nuances. People who decide to pack up may not weigh the pros and cons in a rational manner. But the Deficit of Hope – a composite phenomenon in our minds, built up over time – might well be the decider for some.

Of course, the Deficit of Hope affects everyone. Many among us lead ‘lives of quiet desperation’, to use Henry David Thoreau’s phrase, and that’s far from healthy. We are said to have exceeded USD 2,000 per capita GDP, but income disparities are greater than ever. One in five Lankans has psychiatric issues.

What can be done to enhance our nation’s Hope Quotient?

Governments can’t legislate hope, nor can their spin doctors manufacture it. Just as well. Hope stems from a contented people — not those in denial or delusion — and in a society that is at ease with itself.

We have a long way to go.

Restoring hope isn’t a task for the government alone. We’ve all contributed to its erosion — hands up anyone who has never bribed or jumped ahead in a waiting list through connections.

Good laws and functional institutions are necessary — but not sufficient. We also need an environment where anyone from any background feels there is a greater chance of making a good life here than anywhere else.

Until enough young men and women feel they are equal citizens, the outward march of genes and brains will continue.

Science writer and columnist Nalaka Gunawardene always asks more questions than he can answer. He blogs at nalakagunawardene.com