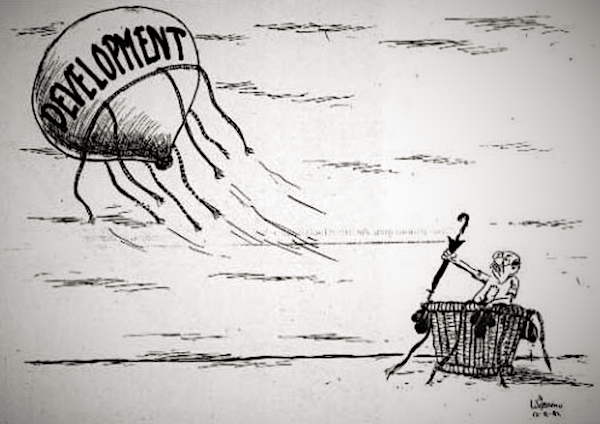

Cartoon by W R Wijesoma – Development that leaves some behind

[Note: This was originally written as part of the When Worlds Collide Sunday column in Ceylon Today, and published on 9 December 2012]

Paul Hermann Müller (1899 – 1965) was a Swiss chemist. He won the 1948 Nobel Prize in physiology (medicine) for his 1939 discovery of DDT’s insecticidal qualities and its use in controlling disease carrying mosquitoes.

That knowledge was soon put to wide use. DDT was sprayed during the latter part of World War II to contain malaria and typhus among troops and civilians, and then adopted as an agricultural insecticide.

Christopher William Wijekoon (CWW) Kannangara (1884 – 1969) was Lankan lawyer, legislator and effectively the country’s first minister of education during the pre-independence era. In the mid 1940s, he introduced far reaching reforms in that sector, enabling children from all levels of society to study from kindergarten to (and including) university level for free.

It’s unlikely that Müller and Kannangara ever met. But their legacies have impacted twentieth century Sri Lanka’s development process in ways that neither individual could have imagined.

In both respects, 1945 was a watershed year. Dust was still settling on the Eastern and Western theatres of war thousands of miles away. The sun was slowly setting on the British Empire. In Ceylon, the movement for political independence was gaining momentum.

On 1 October that year, Kannangara’s educational reforms came into effect, having survived stiff opposition in the State Council and sections of the media. A quiet social revolution was launched.

Around the same time, by coincidence, Ceylon became the first Asian country to develop a scheme of indoor industrial spraying using DDT. Memories of the devastating malaria epidemic of 1934-35, which reported 5.5 million cases, were still fresh in people’s minds.

In 1946, when spraying commenced in earnest, the island still had around 3 million malaria cases, high for a population of 6.6 million (1946 census). With widespread use of DDT and other measures, there was a drastic reduction: down to 7,300 cases in 1956 and just 17 in 1963. (There was a resurgence in the late 1960s which took two more decades to bring under control. But that’s another story.)

DDT Generation

There was another population census in the year we almost beat malaria: it returned a head count of 10.58 million – a 60% increase in just 17 years. That was due to post-war and post-independence baby booms, combined with a reduction in deaths from malaria and other infectious diseases. I have called this Sri Lanka’s DDT Generation.

This demographic wave was the first to benefit from free education. It inspired a tide in rising expectations and aspirations that has preoccupied every Lankan government in office since the 1950s.

Sustained investments in public health and education yielded impressive social indicators. Life expectancy went up, and infant deaths came down. As a nation, we quickly added years to life. Adding life (quality) to years proved harder.

It’s these demographic and aspirational imperatives that all development responses in independent Sri Lanka addressed. That includes the Green Revolution of the 1960s and the Mahaweli River diversion programme of the 1970s.

Such development was pursued under considerable duress: two youth insurgencies in the south, and one protracted separatist war in the north and east. While these conflicts arose from multiple causes, the mismatch between aspirations and opportunity added to the social tensions.

By the time a pro-market government was elected in July 1977 with a five-sixths majority, the “DDT Generation” was rising in the work force.

President J R Jayewardene, himself a former finance minister, correctly read the writing on the wall: a massive demand for more jobs, higher incomes and better infrastructure. How his government responded to that challenge is still being hotly debated 35 years later. But then, it’s easier to be critical in hindsight.

As the Jayewardene juggernaut flexed its muscle to make sweeping policy reforms that, in turn, triggered massive societal changes, only a few public intellectuals and activists dares to question — let alone challenge — any of it.

Mahaweli diversion

Systems ecologist Dr Ranil Senanayake did so – and paid a high price. For a short while in the late 1970s, he worked as an advisor to the Mahaweli Ministry. But when he questioned the mega-project’s development premises and dubious ecological practices, the minister promptly sacked him.

Did anyone at the time offer viable alternatives to the big and quick Mahaweli, I asked Ranil in an interview earlier this year. He strongly believes there were other options that were soundly ignored.

For example, instead of a few large dams, many medium sized ones could have generated the same or higher quantities of electricity. But that wasn’t glitzy enough.

“The idea was to grab the (aid) money and put up the largest possible things! Also, they were making huge reservoirs without consideration of the silt load coming off the mountains…So the huge investment we were doing was being ‘discounted’ almost from the time we were constructing!” Ranil says.

My long conversation with Ranil (“Remember the Mahaweli’s Costly Lessons!” on Groundviews.org, 3 June 2012) is highly relevant in view of today’s massive infrastructure development.

The current ‘development spurt’ is comparable to the Mahaweli. Now, as then, a strong government is bulldozing its way through without adequate public debate of the cost-benefits, choices and alternatives.

How many discordant voices do we hear this time around?

Development of the kind we have had in Sri Lanka is certainly imperfect.

Failures there have been many – of vision, leadership and implementation — some far more costly than others.

Yet, it serves little purpose now to question the motives of those who shaped and implemented development policy decades ago. They had to cope with the confluence of DDT and CWW legacies…

It would be more instructive to dispassionately critique that development’s impact — and learn from it. The Centre for Poverty Analisys (CEPA), a think tank, is aiming for this at their annual symposium on December 11 and 12. This year’s theme: Reimagining Development.

Imagination is more important than knowledge, as Einstein once said. For imagination to be meaningful in development debates, however, it needs to be rooted in ground realities and informed by analysis. Run-away imagination of the fanciful kind, which some of our environmentalists indulge in, won’t solve the tough problems of today.

Yes, development planners must belatedly question their blind acquiescence at the Bretton Woods ‘temples’. Likewise, development researchers and activists must also rethink on their uncritical hero worshipping of those who challenged the status quo, such as Ernst Schumacher, Edward Goldsmith and Rachel Carson.

Village in the Jungle

The bottomline: inclusive development is all about creating choices for everybody – and ensuring that nobody gets left behind. Not quite rocket science, but a bit harder than launching satellites…

It’s a century since an empathetic colonial officer named Leonard Woolf wrote one of the most evocative novels based in Ceylon. The Village in the Jungle, first published in 1913, was based on Woolf’s experiences on the island from 1904 to 1911, culminating as assistant government agent of Hambantota.

The novel captures the harsh reality of an impoverished village, where men and women were completely at the mercy of the encroaching jungle, assorted disease, unkind climate and uncaring government. Multiple hardships fuelled suspicion, fear and superstition among them.

A century on, our jungles have receded, and Hambantota is the new epicentre of fast-tracked development. But significant numbers of rural and urban poor still struggle with many forces that once bedevilled the residents of Woolf’s Beddegama.

Modern day Silindus and Punchi Menikas walk among us, leading lives of quiet desperation. They have been bypassed by decades of development. Cosy slogans and romanticised strategies – many of which don’t work at the scales or speeds required – will not liberate them.