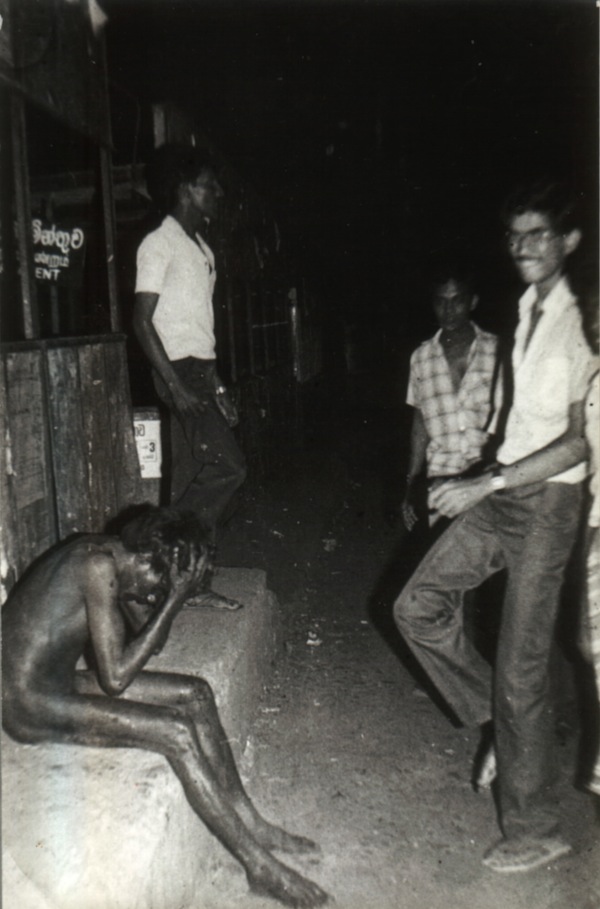

Photograph by Chandragupta Amarasinghe, courtesy Thuppahi’s Blog

[Editors note: Part 2 of this essay can be read here.]

Looking back at the July 1983 disaster, almost 30 years later, it would be natural to query how key policy issues now critical in the discourse on disaster management, like good governance and Human Rights, affected the decisions made by policy makers and implementers as they handled the evolving situation.

A Presidential Commission some years ago, a late response to persistent public demands for ‘truth and reconciliation’ as to what happened, was one not altogether successful, attempt.

The jury on the case is still out, in a manner of speaking.

This present recounting of events and actions of 1983, as far as memory and available documents allow, is that of an actor who was at the centre of the Administration at the time. It attempts to assess the then Government’s ‘management of the situation’ from the point of view of those officially charged with addressing the situation that had arisen in the wake of uncontrolled and widespread rioting in Colombo and elsewhere in the country. Viewing 1983 from this angle may provide a further layer of ‘truth’ in the collective accumulation of knowledge of a national disaster which continues, and will continue, to interest writers, historians, political analysts and the general public alike.

In 1983 the decisions taken and the activities engaged in, under what were termed ‘Essential Services’, were those deemed appropriate then in terms of current (1980’s) norms and best practices. Large ‘gaps’ in norms currently expected to be followed by States would be observed as 1983 was one of the first major man-made national disasters handled by the nation State, the 1958 Emergency being less widespread or long lasting. There was much to learn at the time and there were few examples to be followed or lessons learned from the past. As a case in point, the experience and work of institutions such as UNHCR of the UN system or of ICRC or Save the Children and other international NGO’s and humanitarian agencies were hardly known and were yet to be operational in the country. The present gamut of rules and practices governing the treatment of internally displaced persons or ‘refugees’ were still unknown and probably yet to be internationally formulated.

What seems remarkable now in a review of 1983 practices at this stage is the similarity to the norms of good governance and the ‘rights perspective’, found in the ad hoc measures employed by the actors managing the disaster then both in government and in civil society. In great measure these actions seem to have been based largely on the personal perceptions of justice and fairplay of the actors concerned.

To that extent this study of perspective and praxis at a time of national crisis would have some value and validity.

The Context

‘July 1983’ was by the reckoning of most observers, local and foreign, the largest and most serious disturbance involving the Sinhala and Tamil ethnic communities in Sri Lanka’s modern history up to then. Both in terms of the consequences, political, social and economic – lives lost, persons temporarily and permanently displaced as refugees, homes and industrial property destroyed and ethnic harmony irreparably damaged, and the magnitude – its spread across the country, intensity and duration, it surpassed all of the other man – made disasters the country had earlier faced. The ethnic disturbances of 1958, 1977, 1979 and 1981 were serious in their consequence for unity and ethnic harmony but 1983 had a profound significance for the country’s territorial integrity as well. Never again were things to be the same. The Sinhala (Buddhist) -Muslim riots of 1915, a serious religious clash and the only one of its kind in the colonial period, which is writ large in the history of the country mainly because of the severity through which it was controlled by the colonial government, was of a quite different quality and nature.

As the major man – made disaster in Sri Lanka’s post – colonial history, July 1983 is referred to in the Tamil narrative as a pogrom against the Tamil community. The Sinhala narrative would be more inclined to term it an

ethnic riot in which both sides trade mayhem and destruction on the other. The difference in conceptualization, definition and collective memory is significant and accounts for much of the complexity in the political management of the disaster. Particularly in the Tamil diaspora, scattered around the globe, the memory of the July 1983 incidents, adding to those of 1958, 1977, 1979 (the destruction of the Public Library in Jaffna) and 1981 is one of burning – unmitigated, brutal physical assault and harassment of innocent Tamil civilians[i] by demented Sinhala mobs while the Police force, largely, of a callous and partisan government stood looking on. As evidence of this indifference by the Government to the sufferings of the Tamils through mob violence, reference would be made in the Tamil narrative to the belated declaration[ii] of the Emergency by President J R Jayewardene in July 1983. Curiously, this same feeling of a deliberate late response to a volatile situation in which Tamils would be subject to harassment, has been seen in the Tamil diaspora consciousness regarding Prime Minister SWRD Bandaranaike’s declaration of emergency in 1958.

In the Sinhala memory (particularly among some urban elites and those who happened to be not present in the country at the time ) July 1983 was perceived as a justifiable repeat performance of the past, where urban Tamils especially who were having it good, in secure Colombo, were now been given a ‘taste of their own medicine’ for the murder of Service personnel and innocent Sinhala villagers residing in the North and East.

The major difference between ‘1958’ which propelled the first wave of professional Tamil migrants to Australia, Africa[iii] and the West, and ‘1983’ was that the LTTE had now emerged as the armed opposition to the Government forces. Led by Prabhakaran and evidently trained and equipped in south India they were expected by their sponsors to put up a fight on behalf of the Tamil minority and trade blow for blow with the government forces. Concepts like terrorism, ethnic cleansing and genocide had not yet entered the discourse but the writing on the wall for a more intensive phase of insurgency and – albeit, by surrogates, the ethnic conflict – between the LTTE and the armed forces of the government – had appeared. Highly biased, sometimes planned and almost always irresponsible reporting by both the State controlled and independent media had much to do with the totally contradictory[iv] nature of the collective ethnic memory on both sides of the divide of virtually the same set of incidents.

It is the fact that in 1983 the Sinhala side had the support of the Government, especially the Army and the Police, in large measure. On the other hand the Tamils did not, except for a limited extent in the Northern and Eastern Provinces, have some official (public servants) and Police assistance to help them in the immediate aftermath of the violence. Given the many reports of the one – sided nature of the assaults on people and property all over the country by hoodlums (sometimes assisted by off-duty government security personnel) on mainly members of the Tamil community, not sparing the ‘Indian Tamils’ on the plantations, and the lukewarm support of the State in providing effective support to those under threat, the ethnic violence of 1983 has been more accurately described as a pogrom rather than the euphemistic ‘ethnic riot’[v] which became the preferred official term.

Official spokesmen on behalf of the State have referred to the killings[vi] of Tamil civilians and the destruction in 1983, as an ‘aberration’ that does not truly reflect average Sinhala attitudes towards the Tamil people. It is a fact that many middle – class Sinhalese can refer to instances where they offered refuge to Tamils fleeing from the mob, often at personal risk. Yet, although there were undoubtedly several such instances of personal friends, colleagues and long – standing neighbours doing so, this can by no means deny the existence at the time of a pervasive deep – seated collective hostility towards the Tamils as a political, economic and social community in active competition with the Sinhalese majority.

In the higher echelons of the Government, including that of the President and members of the Cabinet, while there was the knowledge of the build – up of ethnic hostility (and even some active promotion of it according to some sources) the Government was mostly unprepared for the ferocity and rapid spread of the attacks against the Tamils throughout the country once it sparked in Colombo. Political commentaries, local and foreign, range over the following reasons to explain the outbreak of the ‘pogrom’ at this particular time;

- The increasing strength of the Tamil militant groups, especially the LTTE, with assistance received from abroad and local encouragement and the need to ‘nip this in the bud’ by pre-emptive strikes at their civilian supporters especially in Colombo

- Hostility at the apparent affluence and well being of the Tamil community in Colombo and its environs who were benefitting from President JR Jayewardene’s ‘open economy’ and the need ‘to cut them down to size’. A reflection of this latent hostility were public comments about ‘the growing size of the Tamil woman’s pottus’ which apparently now adorned the

foreheads of the Tamil female.

- Deep political resentment against President Jayewardenes’s administration for substituting a fraudulent Referendum in 1982 in place of the General Election which should have occurred in that year – five years after the General Election of 1977. The people’s choice to elect a government was apparently thereby frustrated and certain political parties angered at this loss of the opportunity for a change of government at the level of Parliament, would have been prepared to take advantage of any situation to make things difficult for the government. This was presumably the reason for the President’s fanciful theory of a Naxalite plot which had caused all the trouble and was aimed at stirring up communal trouble and through this the downfall of the Government . The need to find a scapegoat (a familiar route taken by most Sri Lankan governments,) resulted in the jailing of the popular young politician Wijaya Kumaratunga (who later became President Chandrika Kumaratunga’s husband) and the banning of the JVP.

- The persistent belief that 1983 was engineered by the Administration itself (the fact that the mobs were armed with Voters Lists[vii]indicating which homes were Tamil ones buttressing this theory) presumably to

- teach the Tamils to behave themselves as a minority and not get ‘too big for their boots’. The reasoning was that the ‘Open Economy ‘ had been particularly favourable to Tamil businessmen and the attacks on business establishments and factories[viii] in the suburbs of Colombo testifying to this pattern.

- To show the Sinhala majority that the Government was not to be pushed around and would stand up to counter the militants ambushes and hit and run raids.

- Prove to its own Army and Police that it the Government was on their side and were willing to allow a certain laxity of Departmental rules so that old scores might be settled in a kind of rough justice and the Tamil civilians who ‘secretly supported’ the militants taught a lesson.[ix]

And finally, in this discussion on the importance of context, the observation that ‘1983’ is of ‘foundational importance[x] in the country’s modern history. Political analysts have now begun to date the start of Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict from July 1983. The island-wide incidents which occurred at the time are widely accepted as constituting a defining moment in the history of Sri Lanka. The second great wave of Tamil emigration commenced after July 1983. The Tamil diaspora not only increased in membership but now had a cogent visual story to support their claim for a separate state. Thoughtful Sri Lankans and civil society groups also emerged who agonized for a reform of the structure of the State. It, in many ways therefore marked a defining moment in the history of Sri Lanka. No longer, even after normalcy was restored after several weeks, could it be ‘business as usual’.

Handling the Disaster

The extended discussion above of the complex, and often contested, issues relating to the origin of the disaster, its magnitude – island wide and not location specific, its effect on a section of the community – ethnic Tamils – wherever they lived including the plantations -and depth – affecting education, employment etc made it incumbent that the structures that were set up to handle the disaster to be located as high as possible in the Administration to be capable of dealing with the multifarious needs which presented themselves immediately in the short term and on a long – term basis as well.

The system for delivering relief, rehabilitation, reconciliation and so on, had to be set up expeditiously, be multi functional, effective through access to the topmost level of Government and endowed with flexibility to set priorities and even change direction with minimum delay. The management system devised for handling the disaster by the Government attempted to accommodate all these varied elements.

Basically, it built on the experience that the country had acquired in dealing with natural and smaller man-made disasters in earlier times; This usually was for the Government to be the main driver; responsibility for delivery resting on a single individual with proven track – record, vested with wide – ranging powers cutting across existing bureaucratic bounds and borders, working towards prescribed targets and assured with the certainty of unlimited human and material resources. Emergency powers, through a Gazette Extra-ordinary which superseded existing law and procedure was the foundation of the structure.

Governance Functions – Setting up the central infra-structure and building capacity

Along with the President’s declaration of the Emergency and the imposition of the curfew on the Tuesday July 26th following Sunday July 24th evening’s outbreak of violence in Colombo city, the Cabinet at its specially convened meeting agreed that a new institution – of the Commissioner – General of Essential Services – should be established endowed with adequate powers and sufficient funds, to;

- bring the situation under control

- take such remedial measures as needed to provide relief to all affected, and

- restore normalcy

Since the realization of this goal required the coordination of several government agencies, the non- government sector and the private sector, a senior official with the necessary experience located close to a high point of political power was deemed to be the best choice. Bradman Weerakoon who then held the office of Secretary to the Prime Minister – (then Ranesinghe Premadasa) was appointed by the President, in terms of Regulation 10 A (1) of the Emergency (Miscellaneous Provisions and Powers) Regulations as Commissioner – General of Essential Services for the whole of Sri Lanka on 30th July 1983.

The duties of the CGES under Regulations made by the President in terms of Section 5 covered the following;

- Execution and co-ordination of all activities relating to the maintenance of essential services

- Appointing by name or office Deputy Commissioners and Assistant Commissioners with delegated powers for the performance of duties. (All Government Agents of Districts in which there were persons affected by the violence were appointed Deputy Commissioners with full powers to act on Weerakoon’s behalf. Systems were put in place for full information flow and oversight of actions taken under delegated authority.)

- The exercise of similar powers, as those conferred by Emergency Regulation 8 on the Secretary of Defence or any Co-ordinating Officer appointed under Regulation 70. (The significance of this was that the primacy of the civil authority was recognized and civilian needs given preference over military/security reasons. Most Districts had had Coordinating Officers –usually senior military officers – who were not too successful[xi] in co-ordinating civilian heads of Departments. The new Presidential Order had the effect of redressing the imbalance between military and civil power.)

The newly appointed CGES determined that the priority actions to be taken were

- Establishment of a centrally located Headquarters with easy access to those affected, space for a growing staff, parking for relief vehicles, with all necessary infrastructure for effective operations to commence immediately. The entire Royal College premises in Reid Avenue, Colombo 7, along with the adjacent playing field were requisitioned under the Emergency Regulations as the central Head quarters and held by the CGES for the critical first four months. In addition the Government Agents of the affected Districts were appointed as Deputy Commissioners by the CGES and delegated necessary powers. The relevant Kachcheri (G A’s Scretariat) functioned as the Branch of the central Headquarters.

- Recruit within a few days an adequate senior staff and support staff who could manage the diverse duties and responsibilities devolved on the CGES. (See Organizational Chart of the CGES Office below for structure of Responsibilities).

- Since there was no time for an elaborate recruiting procedure to be followed initiate a system of personal selection that worked. The CGES himself chose the senior management team- the 8 Deputy Commissioners in charge of Welfare Centres, Government relations, Media and Publicity, International Relations, Transport and Communications, Resource Mobilization, Finance and Accounts etc. This was based on his personal knowledge of the capacity of the officer selected for hard and prolonged work in a situation of some personal risk, his/her known attitude to the ethnic problem and awareness of minority disabilities, capacity to decide on each emerging situation on his own and take decisive action and the certitude that he/she would be covered by the CGES for all bona fide actions). Special consideration was given to the officer’s track record of empathy towards the vulnerable in earlier situations such as provision of flood/drought relief etc and to any expressed views on the ethnic question. Ability to work in, and as, a team member and incorruptibility scored high in the selection. The Commissioner – general himself encountered not a single instance of political direction by the President, PM or Minister regarding choice of his officials, or the procurement and award of contracts, the major driver of corruption.

- In regard to support staff and drivers, the CGES used the well – known, historically approved practice of 1 x 10 ie permitting each superior officer to choose up to 10 support staff for whom the senior would bear responsibility for efficiency and integrity. Special permission was obtained to effect the reemployment of retired public servants of quality.

- Throughout, HE the President to whom the C-G ES reported was totally supportive.

- As an incentive for the late hours and risks the entire staff would be subject to, all those employed, other than the CGES, were to be compensated for with salaries which amounted to one and a half their substantive monthly salaries.

Resource Mobilization

Finance and fund raising

A start up grant of Rs 50 million from the General Treasury, by order of the President, enabled work to begin almost immediately and settle claims of NGO’s who had provided shelter and food from the start. Strengthening of basic needs of IDP’s like water supply, sanitation and electricity in the temporary shelters provided by mainly churches and schools and manned by NGO’s was a high priority element, and directions made by CGES to the Colombo Municipality, Water Supply and Drainage Departments, Railway, CTB etc were acceded to with alacrity. The technique followed was to speak to a colleague in the public service – Secretary to the Ministry, Head of Department, Assistant Secretary, chief clerk as the case may be and get the job done a.s.a.p. The ‘old boys’ network proved exceedingly effective.

Donor assistance

From the very start, following the Governments appeal for international assistance, foreign and local donors besieged the CGES’s office offering support. Donor coordination and prioritization became very necessary so as not to be swamped with the weight of official and personal generosity. All the Government’s traditional donors responded to the general appeal and lists of needs – to be updated, were urgently called for from the Government Agents who were Deputy Commissioner Generals.

Local NGO#s and INGO’s were the first line of support and their attempts were dovetailed with the work of Government agencies making them feel a sense of ownership with the official programme. NGO’s with special interests, like Women, Children, the disabled etc were provided with easy access into the Welfare Centres and the opportunity to promote their particular programmes. In the process some evangelical religious organizations too were prominent but since mental relief too was essential to many, no one was left outside. The policy as far as access to the camps was concerned was that all humanitarian workers and organizations were welcome – the more the better!

Victim participation and Empowerment

In Colombo, around 100,000 displaced in the first few days were accommodated in over 35 temporary welfare centres. The involvement and participation of the residents themselves in the running of the Welfare Centre’s, (WC) ensured that the rights perspective was entrenched almost from the beginning. The welfare of women and children received a prominent place mainly due to the virtual self-management of the Centres by committees chosen by the residents. Heavily limited space in what had been classrooms (several prominent schools having been requisitioned) was carefully apportioned as family private space. The voluntary Centre committee generally had a mixed gender and class structure each Welfare Centre having a population of professionals as well as working – class members. This class structure permitted a division of labour – between ‘planner and worker’ which replicated life in the outer society. Communal cooking in particular was organized on this pattern and resulted in discipline, economy in use of dry rations supplied and punctuality in service.

To be continued…

The author was at the time of the 1983 anti-Tamil pogrom Secretary to the Prime Minister and Commissioner-General of Essential Services (July 1983 – April 1984)

[i] The title of the book by Jean Arasanayagam, reputed diasporic writer and poet, ‘All is Burning’ is illustrative

[ii] Although serious incidents of assault of persons and burning of shops and homes were being reported from late Sunday evening around Borella as the news of the cremation of the dead soldiers spread, the President delayed the declaration of the Emergency and imposition of curfew until Tuesday afternoon.

[iii] See George Alagiah ‘ A Passage to Africa’. Alagiah describes how his father an Executive Engineer in the P W D very soon after the incidents in Colombo in 1958, grabbed the Right to Retire option offered to Tamil officers and went off to Ghana.

[iv] For an example of selective reporting which had enormous significance later on, note the non -reporting of the fact that soon after the ambush at Tinnevelly on July 27th which resulted in the death of the 13 soldiers, there were reprisal shootings by the Army which had caused the deaths of at least 50 civilians. The Government Agent, Jaffna has reported that he had repeatedly reminded the authorities of this and requested due publicity but his pleas remained unanswered.

[v] Students of ethnic conflict have observed how in the violence in Northern Ireland, Unionists and the British Government would refer to the ‘disturbances’ or ‘problems’ in Northern Ireland..

[vi] The official figure of those killed is around 3000. Anecdotal estimates would put the number much higher, perhaps around 10,000.

[vii] The easy availability of Voters Lists could have been due to the fact that the Referendum had been held only some months earlier.

[viii] A very high proportion of the factories and business establishments were Tamil owned viz;

[ix] Some of these complex undercurrents were evident in the testimony given at the Presidential Commission of Inquiry ( the Truth Commission) which belatedly inquired into 1983 in the year 2000.

[x] ‘1983’ has been the subject of several hundred articles and books both academic and literary and as previously mentioned the subject of a Presidential Commission of Inquiry

[xi] I had personal experience of this in Amparai during the 1971 emergency. A Naval officer – a Liieutenant Commander was appointed over the Government Agent as Co-ordinating Officer. He had little idea of the way civilian governance (consultation/dialogue etc) functioned and his overall performance was unhelpful.