Image courtesy ITV News

“It was under these circumstances that Rajapaksa agreed to forego his own limousine and travel to Marlborough House at Pall Mall in an unmarked vehicle belonging to the Metropolitan Police . The President and First Lady entered Marlborough House premises in a Range Rover bearing the number plate VX 12 CYY. The vehicle did not fly the lion flag for obvious reasons.

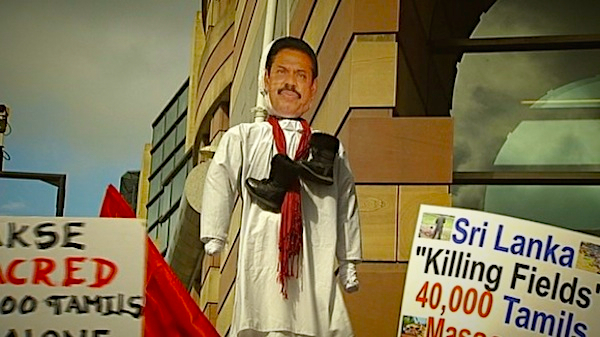

Thousands of demonstrators mainly young Tamils from England,Scotland, France,Germany and Switzerland massed outside Marlborough House ,chanting slogans against President Rajapaksa . They also waved placards and held banners aloft. An effigy of the President as if hanging on the gallows was also dragged and carried about.It was later burnt.

A recurring theme in the slogans chanted was “Sri Lanka President War Criminal”. This cry went up loudly whenever a guest arrived. The shouts echoed around the forecourt as each of the 70-75 guests went in.” – DBS Jeyaraj[1]

DBS Jeyaraj is not a representative of the Tamil diaspora that has set out to wage war against the government of Sri Lanka. He is a journalist who lives in Canada and maintains links to all sides. What he has reported is quite similar to other reports that have appeared in the media regarding this incident.

At the same time, there was a group of about one hundred demonstrators near the hotel where the President was staying, who called out the slogan ‘Rajapakse is our King’.

President Rajapakse was forced to attend the Queen’s Jubilee celebrations in a clandestine vehicle in the face of Tamil protesters demonstrating against his visit to London. A speech that he had been due to make at a Conference around the same time had to be cancelled. These were incidents that proved to be newsworthy as far as the national and international media was concerned. Many reports described this as a defeat for President Rajapakse and a victory for the international Tamil community.

To coincide with the President’s visit to the UK, there had been a Supplement of several pages arranged in the Guardian, which is one of the UK’s leading dailies, at the cost of millions of rupees. On the same day, the Guardian published a report on the torture of a Sri Lankan Tamil who had been deported from the UK to Sri Lanka following the rejection of his claim for asylum by the Police in Sri Lanka. The report was accompanied by photographs. This report received much more attention than the Supplement.

It is extremely rarely that you hear of a President being forced to travel to a state function in a foreign country clandestinely, in a car which does not bear the flag of his country. As pointed out b y the Ravaya and other newspapers, this is a humiliating experience. But in the political arena, such a fate may come not only to President Rajapakse but to any other politician.

We can fund such examples in Sri Lanka itself. Recall the manner in which General Fonseka, who had led the ground troops in the decisive battles of the war, was forcibly dragged off to a prison cell by those who had served under him as junior officers. Libyan leader Gaddafi, who was known as the Lion of the Desert, was killed as he pleaded with his assassins, asking them ‘Why?’. Egyptian leader Hosni Mubarak is today condemned to spend the rest of his life in prison for ordering the shooting of peaceful protestors. In our villages, there is a saying that when the time of Saturn (the senasura) comes around, even a king will be reduced to eating ‘bata’ leaves.

The difference is that Mahinda Rajapakse has had to confront this political debacle while he is a President who enjoys the support of his people. There is no way that he will have to face a similar humiliation in Sri Lanka. However, what this incident draws our attention to, is that there is another level of political reality that has a direct impact on the politics of our country. This is created by the global Tamil community, who, in spite of the differences among them, are unified by their hatred for the Rajapakse regime.

Unlike the community of nation states that gathers together under the auspices of the United Nations, this global Tamil diaspora has an organic connection to the Sri Lankan Tamil community. They maintain direct and regular communication with the national Tamil community on a daily basis, using diverse means, but especially the internet. Therefore, unlike the discussions which take place within the United Nations on Sri Lanka, the victories they extract from humiliating Rajapakse are directly communicated to the Sri Lankan Tamil community.

Including the Si Lankan Tamil diaspora, there are four principal centres of power that are active in the international arena on questions relating to the ethnic problem in Sri Lanka.

First is the community of nation states that we mentioned earlier, that constitute the global international community, led by the western democracies, and articulated through the United Nations system. By bringing about a Resolution on accountability in Sri Lanka at the UN Human Rights Council, they have already demonstrated their influence on the Sri Lankan situation.

Second is the ever sharpening political dynamic in India, calling for a speedy and sustainable resolution of the ethnic problem in Sri Lanka, concentrated in Tamilnadu but rapidly expanding to the national political arena in India.

Third is the international human rights community, led by organizations such as Amnesty international, Human Rights Watch and the International Crisis Group, which have ever widening spheres of influence globally. It is they who bring the most pressure to bear on the community of nation states that we spoke of earlier, producing regular investigative reports on the human rights situation in Sri Lanka.

The fourth centre of power is what is referred to broadly as ‘the Tamil diaspora’ consisting of hundreds of thousands of Sri Lankan Tamils around the world, who have ably demonstrated the propaganda and communication machinery at their disposal. Demonstrations, fasts, meetings and campaigns are all a part of their toolbox.

We should understand and analyse the political misfortune that confronted President Rajapakse in England by locating within this broad scenario.

It is an undisputed fact that by now, three years after the end of the war, the Rajapakse regime has not shown any inclination to seek a just and sustainable resolution of the ethnic problem in Sri Lanka. They have only succeeded in making empty promises. The main strategy being followed by the Rajapakse government with regard to the ethnic issue is to blunt aspirations of the Tamil people by engaging in infrastructure development that is linked to a process of militarization. Their goal is not to seek a just political solution to the ethnic problem, but to keep the Tamil people of Sri Lanka as a subordinated and subjugated community. If their goal was to resolve the ethnic problem, they would not have discarded the recommendations of the All Party Conference that they appointed, and would not be wasting time with the appointment of pseudo Parliamentary Select Committees.

What needs to be added to this political equation is the fact that there is no strong or decisive voice coming from the majority Sinhala community, calling for a political solution. In the absence of such a voice, the position adopted by the Rajapakse regime becomes accepted, by default, as the will of the Sinhala majority.

It is in the context of these developments that we should locate the present position of the Tamil National Alliance, which is the main political representative of the Tamil people in Sri Lanka. Their opinion is that we should seek a resolution to the ethnic problem in Sri Lanka with the support of the international community. This is a clear indication that they have by now accepted that the Sri Lankan state will not offer them a just political solution. Now we can see that not only the Sri Lankan Tamils within the country, but also those who form the global Tamil community, have come to this conclusion. As was made clear by Mr. Sambanthan’s speech in Batticaloa, the political strategy of the Sri Lankan Tamil community that is not subservient to the government should be to act in a manner that will show the international community the reality of the Sri Lankan situation.

So let us examine the scenario that lies before us. The majority of the Sinhala polity, of which the Rajapakse regime is the symbol, is not ready to offer an appropriate resolution of the ethnic issue. The four key centres of power that lie outside the country that I have outlined above are all standing together with the Tamil people of Sri Lanka to support the goal of a political solution.

Seeking a political solution to the ethnic problem in Sri Lanka has become the collective aspiration of the international community and the Sri Lankan Tamil people.

The future that stretches out before us in the context of this scenario is frightening. This is how pro-Rajapakse political analyst Dayan Jayatilleke sees it:

”In 1990 that Council which had been set-up under the 13th amendment, made a Unilateral Declaration of Independence, with tens of thousands of foreign troops on the soil of the area. Who is to say that a future Council which is similarly committed to going beyond the 13th amendment will not do likewise, only this time with foreign troops being invited in by the rebellious Council? Why would any responsible state take that risk?

How then to resolve this complex conundrum? Fortunately there exists a legal and constitutional pathway: that of an interim administration. An interim administration comprising of all parliamentary parties currently representing the relevant (Northern) area, appointed in proportion to their parliamentary strengths relevant to that area, may be a provisional solution; a stop-gap measure.”[2]

This proposal shows us how the national and international forces described above are pushing the Rajapakse regime to a crisis.

The Rajapakse regime cannot allow the Provincial Councils of the North and East of Sri Lanka to fall into the hands of the Tamil National Alliance in the face of current development in India and in the international arena which leave it at a distinct disadvantage. But they cannot also deny the will of the majority of the Tamil people and hand over control of those areas to their henchmen because they know that any attempt to do so would result in a worsening of the situation. Such a move would lay Sri Lanka wide open once again to a complex cycle that may lead to a conflict that will invariably stretch beyond its borders.

There is one path to emerge from this crisis; that is, to renounce militarism, and to move forward to a process of democratization. A lasting and just resolution of the ethnic problem can be created only through such a process.

If the Rajapakse regime is to prevent the echoing and re-echoing of their humiliation in London, they must achieve a positive transformation of their strategies and tactics. This is what has been made clear to them and to all of us by the incidents in London.