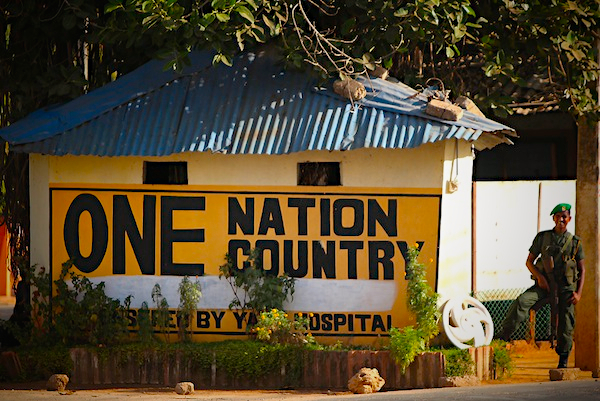

Photo courtesy: Steve Chao /Al Jazeera via JDS

With our Government busy defending itself from war crime allegations, protecting the sovereignty of the country and advising the common man to say ‘no’ to Google, the Tamil leadership and, of course, the Tamil Diaspora dreaming of some mode of foreign intervention and drooling over the latest Channel 4 documentary, the Muslim Community deeply wounded by the recent developments in Dambulla, and the common man constantly worried over the ever increasing fuel price, it’s understandable why the journey towards achieving true and authentic reconciliation has become such a tricky business in our country. With so many external factors coming into the equation (of achieving reconciliation) even Albert Einstein would have had trouble sorting things out and moving forward.

The intention of this article is to look at reconciliation from a different angle; an angle that helps simplify the equation – eliminate as many external factors and make the concept as practically attainable as possible. The important thing to realize is that there is no clear road map to a perfect reconciliation process, different people will have different opinions and the balance between the importance of transformation at personal level and systemic level will always be debated. This makes the road to reconciliation, essentially, an adventure, in which we experiment and learn. And intentions matter most.

A search query on Google for ‘definitions of reconciliation’ will give you 25.1 million hits, which means that the answer is not straightforward and has multiple dimensions. In his widely acclaimed book, Overcoming Apartheid, James L. Gibson puts the problem in correct perspective, ‘the problem with reconciliation is not that it is devoid of content; the problem is that reconciliation is such an intuitively accessible concept that everyone is able to imbue it with her or his own distinct understanding.’ The Greek word for reconciliation is tikkum olam, meaning to heal, to repair and to transform, and this can be treated as the meaning of reconciliation in a nutshell.

Why Reconciliation?

Unless we come up with healthy answers to this question, there is no point in discussing further, even if we do, there won’t be much difference between us and the old uncles who muse over cricket after washing out their day’s sins with a glass of whiskey. Reasons such as we are all human beings and we have the same colored blood running in our veins may serve as good starting points, but take us no further. Such points aid, mostly, towards answering the question ‘why should we be divided?’ rather than ‘why should we unite?’ – Which is, in fact, the question to ask and answer. Answers to the question, ‘why reconciliation?’ Should not, entirely, be emotional; there should be a fair quota of logical reasoning involved.

There are two ways of approaching the question: one, looking back at our history, two, thinking of the future.

Historically, in Sri Lanka, Sinhalese, Tamils and Muslims did co-exist for centuries. The way of life was such that Hinduism and Buddhism, during Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa Dynasties, had much in common. The Muslims of Mannar had such good relationships with the Tamil people – before the LTTE chased them away – that they even opened their doors and protected the Tamils when Government Forces attacked the Island in 1990. Countless number of such examples can be generated. The state of affairs at the end of four-and-a-half centuries of colonialism – the lack of a common Sri Lankan identity (or Ceylon back then) – is largely to be blamed for what followed in the sixty–four years of independence. The politicians, at the time of independence and those who followed, instead of trying to resolve the divisions and working towards building that much needed common identity either continued to use the divisions for their own vested interests or resorted to an indifferent approach; at the time of independence the potential to build a common identity was very much present before the then rulers blew it with the Citizenship Act. At almost all crucial junctures in our short history of independence we have somehow managed to contribute to the exacerbation of divisions which, ultimately, resulted in bloody violence. History was rewritten, by both parties involved, to better suite their cause and arguments, hatred and racism became the cog wheel of the national cart, and elections were won, solely, based on the better ‘kill ‘em all’ rhetoric. The results of the thirty year long war – deaths, loss of property, a violent culture that tolerates injustices to deplorable levels, innumerable underage marriages, pregnant teenagers, corruption of humanity, fear, frustration, autocratic mindset, intolerance of alternative ideas or perspectives and all other related consequences – serve as good reminders why we, as a country, should never allow hatred to control us, ever again. Unwillingness to learn from our past will prove to be a greater sin than all that we have already committed.

Our actions today will have consequences tomorrow; we all know that. Would you like your children to see what you have seen in your life? Would you like your child grow up in the same hate filled environment? Would you like your child to think of guns and grenades when he/she should rather be thinking of bat, ball and dolls? Would you like your child to hear the same lies your parents told you? That is what the future has in store for us if we do not re-think and act now. It will take decades; it may even take centuries, before we fully pay the price for the wrongdoings of the past generation. And a divided, polarized and suspicious community will certainly not help the future generations. With resources getting scarcer with each passing day, it will not help the future generations if we fight over what little we have, and end up destroying all that we have. We can choose to learn, forgive, ask for forgiveness and reconcile, and in doing so do the groundwork for a better future for our children or dwell in the same hatred, the same attitudes and the same actions of the past generation, and later, possibly in our death beds, share the sentiments of Rudyard Kipling who, after losing his son to World War I, wrote in his Epitaphs of War ‘any question why we died, tell them because our fathers lied.’

A (More) Practical Solution

“No one is born hating another person because of the colour of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than it’s opposite,” – Nelson Mandela, Autobiography.

For most people, the word reconciliation brings to mind a round table, couple of glasses of water, some files and men in neat suits. Even though there is no denying the fact that the systemic aspect – political solution, constitutional changes, parliamentary representation etc. – is a vital component in the overall success of any national reconciliation process, it’s not the only element. A viable political solution does not necessarily solve all the issues related to inter-ethnic conflict – just like the conclusion of war did not. Politicians will change and so will the policies. The story of the 17th Amendment is a wonderful example. Unless relationships are restored there will never be lasting peace; peace will become dependent on ballot counts, every six years.

As noted right at the beginning, the situation that prevails in the country is not ideal for anything good; certainly not for reconciliation. In the three years following the end of war the Government has done very little to promote reconciliation or to win the hearts of the Tamil people or, in the light of recent developments, the Muslim people as well. And you don’t have to be a rocket scientist to figure that out. The question is what do we do till the Government changes its attitude or there is a new regime? Do we sleep? Do we just complain? Do we just criticize the Government and repeat the accusations? Or do we act to bring about a change in the attitudes of the people? ‘People from the bottom have to get their rulers to listen,’ was the cry of respected journalist Namini Wijedasa, in her recent keynote address at the Annual General Meeting of the Citizens Movement for Good Governance. If we want reconciliation, the common man should start desiring it. When there is a powerful unified voice from the masses demanding a national reconciliation process, this Government, the next Government or any Government will have to come up with viable a solution.

This leaves us with just about one option: to work towards building or rather restoring inter-ethnic relationships and making people care for each other. Teach people to love, as Nelson Mandela said. Opportunities should be created for people to meet in safe environments – where there is no fear and equal treatment for everyone – and identify their common links and learn to appreciate their differences. The idea should be to give people a firsthand experience of what it would be to live in a reconciled nation, where equal rights, justice and appreciation of diversity prevail, where people work for the good of each other rather than just for their own. The whole mindset of ‘Us against Them’ should be shattered. People should be directed to build on the common links and explore the various aspects of a common Sri Lankan identity – one that can be embraced by all communities and has equality at its heart. Once friendships are established there, spaces should be created for people to discuss their issues and understand each others’ struggles. We live in a country where terrible things have become so normalized we don’t even recognize it. Slowly but surely these bonds, if nurtured properly, will become stronger. The more friendships that are created the stronger the unified voice will be.

One notable similarity in all the reconciliation related materials available is that words such as process, journey and path make regular appearances along with the key word, meaning that it’s a time consuming practice and requires a long term vision. Hence, any effort to bring reconciliation and thus sustainable peace will have to focus on the youth; the new generation. The youth, naturally, are more receptive. They are always willing to experiment with new ideas. Give them the opportunity – there is no harm in trying. What this country needs is bit of fresh air and young blood.