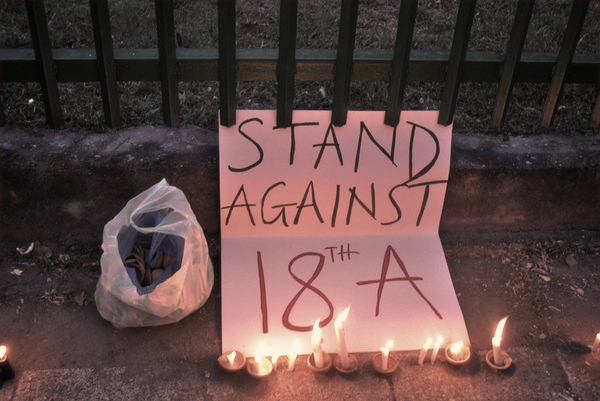

Photo courtesy Vikalpa

September 8, 2010 marked a watershed event in the constitutional history of Sri Lanka. The enactment of the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution on this ill-fated day brought to a close an era in which successive presidential candidates had promised to abolish the executive presidency. The Eighteenth Amendment effectively extinguished the last remnant of hope that this promise would one day be kept. Instead, it has ushered in a new epoch where an over-mighty president for life has become a plausible reality.

The present review examines a compilation of papers critiquing the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution of Sri Lanka. The reviewed publication was produced by the Centre for Policy Alternatives in partnership with the Friedrich-Naumann-Stiftung für die Freiheit. It is presented in five chapters, each dealing with a particular aspect of the Eighteenth Amendment—either in terms of its substance or in terms of the process through which it was enacted.

In the first chapter, Dr. Pakiasothy Saravanamuttu examines the political implications of the Amendment amidst what he describes as ‘the recurring theme of our country’s constitutional evolution’ i.e. the centralization of power in the executive. Crucially, the author adopts a holistic approach to scrutinizing the Amendment. He points out that the removal of the two-term limit must not be examined in isolation even though its proponents argue that it is a ‘franchise-enhancing’ initiative. In combination with the removal of the term limit, the Amendment also erodes the independence of vital institutions including the Election Commission. This invariably weakens democratic structures and the integrity of the electoral process, thereby ensuring the perpetual re-election of an incumbent president and preventing the somewhat attenuated benefit of ‘franchise enhancement’ from reaching fruition.

The author criticizes the capitulation of certain minority groups and the ‘old left’, seduced by the promises of political benefits and rapid economic growth. Referring to the J.R. Jayawardene era, the author concludes that neither long-term political advantage for fringe groups nor accelerated economic growth for the nation emerged from previous initiatives to strengthen the presidency. The author, however, does not directly address the more fundamental question of whether authoritarianism is an acceptable price to pay for accelerated economic growth—if such growth could in fact be achieved. The present regime’s obsession with the Singaporean model betrays the intended trajectory of future politics in Sri Lanka. There is little doubt that economic growth would be touted as the singular solution to the political crisis which confronts the nation today. Many appear to be comfortable with this compromise, provided that economic growth would arrive as promised. This optimism may also explain the public’s general apathy towards the Eighteenth Amendment. Hence debunking the theory that underpins this apathy, and questioning the desirability of an economically thriving, yet politically oppressive society, is required of any serious proponent of political liberalism.

Admirably, the author does not neglect to refer to the failure of civil society to galvanize a critical mass in response to the Eighteenth Amendment. Perhaps this was an aspect that required further reflection, as self-criticism remains an aspect which is woefully inadequate—if not altogether absent—in civil society-led discourse today. This review was written with the luxury of seeing a far more successful campaign against governmental authoritarianism: the public response to the proposed Pension Bill of 2011. Similar to the Eighteenth Amendment, the Pension Bill was also endorsed by the Supreme Court. However, the affected parties, spearheaded by trade unions, staged wide-scale protests effectively halting the government in its tracks. Though it remains to be seen whether the Bill will reemerge in a diluted form, the value of possessing grassroots linkages and appealing to affected masses was evident in this campaign. Civil society actors in Sri Lanka—at least the ones focusing on constitutionalism—have thus far failed to secure resonance for constitutionalism amongst the critical masses. Perhaps this aspect requires a great deal of attention when strategizing future initiatives premised on the defence of liberal democratic principles.

In the second chapter, Aruni Jayakody examines how the Eighteenth Amendment consolidates executive power in Sri Lanka. She concludes that the Amendment ultimately ‘undermines the rule of law…and takes away key mechanisms that seek to ensure the integrity of the democratic process.’ Her defence of the Seventeenth Amendment is noteworthy, as she characterizes the Amendment as essential to halting the erosion of the rule of law. While admitting a crisis in implementing the proposals under the Seventeenth Amendment, the author questions the justifications for repealing the Amendment altogether. She presents a list of alternatives including mechanisms that seek to break the deadlock among minority parties; reinterpreting the minimum requirements of the Constitutional Council; and reforming the Seventeenth Amendment. However, these alternatives are not explored in greater detail. Such elaboration may perhaps be necessary to counter the pragmatist’s response that the Seventeenth Amendment ought to be repealed due to its demonstrably unworkable nature.

Moreover, the author examines the Eighteenth Amendment’s impact on the power and authority of the Provincial Councils and concludes that the Amendment ought to have been presented to the provinces for ratification under Article 154G(2) of the Constitution. One of the clear alterations introduced through the Amendment concerns the composition of the Finance Commission. This Commission is directly responsible for the allocation of resources to the provinces, and thus plays a pivotal role in ensuring fiscal devolution. Hence there appears to be little doubt that the Amendment attracted the provisions of Article 154G(2). Though the author does not directly deal with the ramifications of noncompliance with this procedural requirement, it is dealt with elsewhere in the publication.

In chapter three, Rohan Edirisinge and Aruni Jayakody discuss the Eighteenth Amendment in relation to its assault on the ideals of constitutionalism. The authors observe, ‘[i]f the Constitution can be changed by the wielders of power without the participation of and the concurrence of those whom a constitution is designed to protect, the basic rationale of constitutionalism is undermined.’ The authors criticize numerous stakeholders for their failure to provide the people with a better understanding of constitutionalism and to ensure public participation in the process of constitutional change. The use of the ‘urgent bill’ mechanism is critiqued in particular, as the abuse of this mechanism is said to ‘[rob] the public [of] the chance to be informed, observe or participate in the process of changing the Basic Law that is supposed to protect them from those who wield power.’ The authors correctly argue that the urgent bill mechanism should never be used when engaging in constitutional amendment. Hence the same critique is leveled against the process adopted to pass the Seventeenth Amendment. However, the authors contend that the Seventeenth Amendment enhanced the sovereignty of the people, while the Eighteenth Amendment undermined it, perhaps alluding to the need to adopt a stricter approach when dealing with the latter amendment. Admittedly, the Supreme Court neglected to appreciate the fundamental difference between the two amendments. Yet it seems incompatible with constitutionalism to excuse one amendment from meticulous public scrutiny merely because it appears to enhance the sovereignty of the people, while subjecting to stricter scrutiny another amendment that appears to undermine sovereignty. Moreover, the Seventeenth Amendment had its own set of difficulties, as it altered the constitutional framework under the Thirteenth Amendment, which was carefully negotiated through the input and participation of key stakeholders. Civil society actors appear to have done a disservice to the ideals of constitutionalism, as they neither questioned the process through which the Seventeenth Amendment was enacted nor insisted on a greater level of public participation. This apparent laxity later returned to haunt civil society actors when they challenged the use of the urgent bill mechanism to pass the Eighteenth Amendment.

The authors suggest that there should have been more time provided for the public to participate in the process and for the Supreme Court to assess the constitutionality of the proposed Bill. A determination that the Bill was inconsistent with an entrenched provision of the Constitution would have attracted the provisions of Article 83 of the Constitution. This would only have required that the people approve the Bill at a referendum. The authors neglect to comment on whether this inevitability itself is consistent with the ideals of constitutionalism, as ‘ultra-democratic’ mechanisms such as referenda tend to facilitate majoritarianism and undermine constitutionalism. Hence the strategic value of insisting on a referendum despite its incompatibility with constitutionalism ought to have been discussed in greater detail. The insistence that an unconstitutional Bill requires the approval of the people at a referendum does not translate into an endorsement of referenda as a counter-majoritarian tool. In fact, the use of referenda in matters of constitution making can be deeply problematic, particularly when only a simple majority is required for approval. Thus the motive behind insisting on referenda is both dilatory and pragmatic, as it is predicated on the assumption that, owing to the cumbersome nature of referenda, such insistence enhances the likelihood that the proposal would be altogether abandoned.

Niran Anketell critiques the Eighteenth Amendment Bill Special Determination in the fourth chapter of the publication. The author describes the Supreme Court’s treatment of the effect of the Amendment on the exercise of executive power as ‘cursory and bordering on the superficial.’ He analyzes the applicability of Article 154G(2) of the Constitution and concludes that the failure of the President to present the Bill to the provinces to obtain their views rendered the Bill incapable of becoming law. Since the Supreme Court is not vested with the specific power to strike down a Bill on the grounds of non-compliance with Article 154G(2), the author successfully argues that the failure to deal with such non-compliance did not amount to a final determination on the matter. Accordingly, he concludes that any court may yet declare the Eighteenth Amendment a nullity.

An aspect that is perhaps missing from the analysis is the patent disparity between the draft Bill that was deemed constitutional by virtue of the Supreme Court Determination and the final version of the Eighteenth Amendment. A comparison between the Bill that was submitted to Court and the actual Amendment that passed into law reveals several key changes made during the parliamentary committee stage. This discrepancy casts further aspersions on the validity and indeed the binding nature of the Supreme Court’s Determination. If the Determination was in respect of a version that never passed into law in its entirety, questions of severability may invariably arise. It appears that a Determination by the Supreme Court would not preclude the Legislature from introducing substantive changes to the proposed Bill during the committee stage, which incidentally is not subject to further review. Hence it may have been useful to critique the superficiality of the process itself due to the narrowness of the scope of judicial review under the present Constitution.

In the final chapter, Asanga Welikala presents a lucid analysis of the constitutional rational behind temporal limitations on executive power. The author argues that ‘from the perspective of liberal constitutionalism…the removal of the term limit is a regressive step that would further skew the institutional imbalance at the heart of the 1978 Constitution in favour of what is already an “over-mighty executive”.’ In support of retaining the two-term limit, he cites the American experience vis-à-vis the Twenty-second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The American experience in this regard includes a number of important parallels that were perhaps worth delving into further.

First, the constitutionalization of the two-term limit was largely a response to the four-term presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt. FDR’s charismatic presidency during the Great Depression and World War II guaranteed his ascendency as perhaps one of the most highly regarded U.S. presidents in history. Many regard FDR’s third and fourth terms as indispensable to the United State’s success during the World War. Yet these considerations did not dissuade the states from accepting the Hoover Commission proposals which culminated in the enactment of the Twenty-second Amendment. The normative value of the two-term limit appeared to have outweighed the perhaps pragmatic value of having a strong and stable Executive during periods of turmoil. What is evident from the historical context surrounding the Twenty-second Amendment is that the nation decided to reaffirm the necessity for constitutional safeguards even at the supposed risk of weakening the Executive during future periods of uncertainty.

Second, the American experience also demonstrates the inevitability of an overreaching Executive. FDR’s own record of tampering with the separation of powers through his ‘court-packing plan’ in 1937 and tinkering with fiscal policy through the ‘New Deal’ programs was critical to the discussion, though these initiatives preceded his third and fourth terms. The inevitable trend of executive overreaching is evident throughout FDR’s reign, which no doubt strengthens the argument that even the noblest leader is inclined to test democratic institutions in order to further entrench his or her power. The Twenty-second Amendment was very much a response to this inevitability.

This experience compels a careful consideration of Sri Lanka’s own post-conflict context. The underlying political concerns of minority groups augments the need for reaffirming counter-majoritarian safeguards such as the two-term limit on the presidency. Moreover, as amply captured in this publication, the unambiguous track record of our own executives in attempting to entrench their power, further rationalizes the need for retaining temporal limitations on the presidency. Relative to the American experience, it appears that the context in Sri Lanka supports the retaining of such temporal limitations to perhaps an even greater extent.

In conclusion, what appears to be this publication’s most important contribution to the discourse on the Eighteenth Amendment is its cogent analysis of the constitutional and political implications of the Amendment. The authors successfully capture the myriad dimensions of the debate on the Amendment’s desirability and constitutionality, and present a compelling case for its outright rejection. The true implications of the Amendment are still to be fully appreciated by the critical masses; a predicament that could have been avoided had civil society actors succeeded in presenting the ideals of constitutionalism in a form more readily consumed by the general public. In such circumstances, the publishers ought to consider the value of translating this work into Sinhala and Tamil. Wider dissemination of this work may help create greater political awareness and invite deeper reflection on the constitutional crisis that the Eighteenth Amendment engenders.