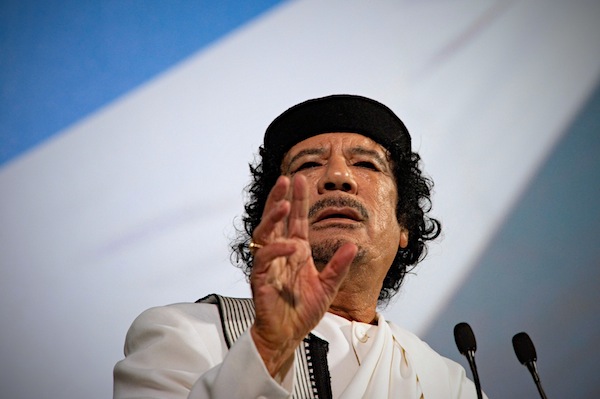

Muammar Qaddafi, Libya’s leader, speaks at an equestrian show at the Tor di Quinto cavalry school in Rome, Italy, on Monday, Aug. 30, 2010. Italy’s 2008 apology to Libya for three decades of colonial rule is paying dividends for Italian companies including Eni SpA and Finmeccanica SpA. Photographer: Victor Sokolowicz/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Libya is the model of the new interventionism and is the latest, successful mode of application of the doctrine of R2P says Paddy Ashdown, writing in The Times.

“…This is what the future probably looks like. Better get used to it” according to Mr Ashdown, who posits it as “a new way of intervening and giving strength to a new strand of international law… Many of us thought R2P would never be more than a piece of well-meaning rhetoric. But Libya has given R2P both form and precedent… Now Libya has offered us a third option. Support R2P with force where it’s possible. Find other means where it isn’t. Assemble a coalition wider than the West. Obtain the backing of international law.” (‘Ray-Bans and pick-ups: this is the future; Iraq-style intervention is over. The messy Libyan version will be our model from now on’, The Times, August 26, 2011).

Influential individuals in the West have begun to refer to Sri Lanka in the same texts, indeed the same paragraphs as Libya. Take for instance, an article in perhaps one of the two most influential publications of world affairs, the Foreign Affairs Quarterly, published by the Council on Foreign Relations. The essay dated August 26, 2011, is by Stewart Patrick, a former Policy Planning Staffer of the US State Department, currently a Senior Fellow and the Director of the Program on International Institutions and Global Governance at the Council itself. Entitled ‘Libya and the Future of Humanitarian Intervention’, the article deals, as the subtitle indicates, with ‘How Qaddafi’s Fall Vindicated R to P’. In a particularly ludicrous but pernicious passage, he writes: “…To be sure, the atrocities Qaddafi orchestrated in Libya prior to the intervention pale in comparison to those committed during the course of other recent violent conflicts. In Sri Lanka, for example, the government killed thousands of civilians while finishing off the rebel Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in 2009”.

Stewart Patrick provides a valuable service by drawing our attention to a brand new policy document of cardinal importance that takes the doctrine of R2P to the next level. He discloses that ‘Lest one imagine that the Libyan case is a one-off, on August 4 the Obama administration released the Presidential Study Directive on Mass Atrocities (PSD-10). The directive defines the prevention of mass atrocities as both “a core national security interest and a core moral responsibility of the United States.” PSD-10 is a groundbreaking document and represents a huge victory for NSS Senior Director Samantha Power, a leading administration hawk on Libya. The PSD-10 recognizes a simple truth: the United States will inevitably confront atrocities that cannot be ignored. The directive expands the menu of policy options available in such cases, which should range from complete inaction to sending in the marines. This escalatory ladder is meant to encompass preventive diplomacy, economic and financial sanctions, arms embargoes, and ultimately coercive action. Realist critics have bemoaned it as a blueprint for interventionism run amok, anticipating meddling in foreign conflicts on a grand Wilsonian scale.’

What are the lessons of Libya for Lanka? The main lesson derives from the very essay that makes the ludicrous and dangerous mention of Sri Lanka. Listing the reasons for the success of the Libyan intervention as a case of R2P, author Stewart Patrick reminds us that “…Qaddafi…had managed to alienate…his erstwhile Arab and African allies…the members of the Arab League, Organization of the Islamic Conference, and Gulf Cooperation Council all endorsed the UN’s declaration of a no-fly zone over Libya, including the use of “all necessary means” to prevent mass atrocities.”

Fareed Zakaria makes quite the same point in his August 23rd essay on Libya, captioned ‘A New Era in US Foreign Policy’. He lists as the second most crucial factor in the success of the Libyan intervention, “Locally recognized legitimacy in the form of the Arab League’s request for intervention”.

The lesson here is manifestly clear, especially when viewed against the success of Zimbabwe, which had the support of its influential large neighbour South Africa. De-stabilisation, hegemonic intervention and regime change are possible only if there is a breach in the wall of neighbourhood solidarity. Already in the sub-region, comprising Sri Lanka’s ‘greater Northern’ neighbourhood, voices redolent of ancient animosity are being raised.

Is there a place for deterrence in Sri Lanka’s strategic options? Our Northern borders are acutely vulnerable for two reasons and from two types of threat, which may interact: a disaffected minority adjacent to a historically hostile and intervention prone area, and exposure of our assets and dispositions to stand-off weapons and aerial strikes. Our advantages lie in a large, patriotic population, a tough armed forces and a proven capacity to fight even in the demographically inhospitable North. A credible deterrent or ‘second strike’ capacity would entail the possibility of protracted asymmetric warfare along a long ‘border’.

This must involve the offsetting of our Northern vulnerability with a strategic reconfiguration of the adjacent Eastern province, in a manner that makes it solidly defensible or a credible jumping off base for Northern operations.

Our deterrent capacity cannot depend upon a vastly expanded army of almost half a million, as a former commander mistakenly called for, because the economic costs would sink the country. Nor should anyone envisage compulsory national service in the form of a draft because the USA itself learnt to its bitter social cost that the best army is an all-volunteer army. However, a recent successful experiment has been conducted in Sri Lanka with the armed forces’ support, for an orientation course of university entrants. In preparation for a worst case scenario, that model could be expanded to provide a huge youth/student populace, including women, trained in the use of weapons, and which could make any invader, secessionist or irredentist puppet regime (and its ‘rebel army’) bleed from death by a thousand cuts. As Fidel Castro once said when Cuba was under threat of intervention, “we shall arm even the cats!”

Sri Lanka must protect itself against two erroneous schools of thought, both of which sin against Realism. One fails to comprehend the basic conflict of interest between Sri Lanka’s national interests and those states that call for so-called accountability hearings. These states are driven by Tamil Diaspora lobbies, contempt for national sovereignty (except for their own) and an emerging Cold War competition with China. The pseudo-pragmatic school of ‘professional’ capitulationists and appeasers fails to perceive the threat from this quarter and the requirement of global resistance. The other school of thought is that of those who fail to understand the imperative need for compromises and concessions on the secondary and the tactical, so that a strong protective ring can be reconstructed on our perimeter, i.e., our neighbourhood, thereby protecting that which is essential: Sri Lanka’s sovereignty, unity, territorial integrity and the gains of the historic military victory.

The most durable defence against interventionism is by simultaneously changing our ‘target profile’ and ‘target hardening’. This can be done only by repairing our internal fragility; removing the discontent and disaffection of the minority at our strategically sensitive Northern periphery. But can that be done and how can it be done? The best answer is in The Fear of Barbarians by Tzventan Todorov, Director of Research at the Centre National de la Recherché Scientifique (CNRS), Paris. In this book, described by the great scholar of international relations, Prof Stanley Hoffman of Harvard and Science Po, as “more than a masterpiece, [it is] a treasure”, Prof Todorov speaks of the need to replace or transform an ethnocracy into a modern democracy: “a modern democracy is to be distinguished from an ethnocracy, i.e., a state in which belonging to a particular ethnic group ensures you of privileges over the other inhabitants of a country; in a democracy, all citizens, whatever their origin, language, religion or customs enjoy the same rights.” (p 67)

Could any imperative be more patriotic? Could any patriotic task be more urgently imperative?