The literary world is now poised on the brink wondering if the Tamil Tigress (Allen & Unwin, 2011) is going to join Forbidden Love (Random House, 2003) and The Hand that signed the Paper (Allen and Unwin, 2000) in the house of literary infamy. Has the Tamil lady who uses the nom de plume Niromi de Soyza[i] woven an autobiographical tale of lies that match those coined by Norma Toliopoulos and Helen Darville who wrote their memoirs as Norma Kouri and Helen Demidenko?

When Kouri’s book was challenged by the Jordanian National Commission for Women on the ground that it contained 70 exaggerations and errors, Random House Australia indicated that “they were satisfied with the veracity of the story, [though] names and places had been changed to protect the identities of those involved.”[ii] Their defense did not hold up for long as Malcolm Knox spearheaded the media questioning in Australia. Random House pulled the book from the shelf [iii] – but that was after the first run of this memoir had sold over 200,000 copies in Australia alone and after “enthusiastic Australians voted it among their favorite 100 books of all time.”[iv]

When Demidenko’s manuscript was submitted to the University of Queensland Press in 1993, they had rejected it,[v] but The Hand That Signed the Paper appeared in print under the masthead of Allen and Unwin in 1994. It is said that the Allen & Unwin editorial staff believed that it was essentially autobiographical, though they persuaded the author to alter the family’s name in the book to “Kovalenko.”[vi] The book won the Vogel Award for a first novel in 1994, which was followed in 1995 by the most prestigious literary prize in Australia, the Miles Franklin Award, as well as the Gold Medal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature. When it was subsequently discovered that Demidenko had no Ukrainian background, a literary storm erupted. This furore was further exacerbated by Darville’s continued evasions as well as her manifest anti-Semitic prejudices.

The issue facing us today, therefore, is whether Tamil Tigress is going to join such ‘august shelves’ in some attic that contains Forbidden Love and The Hand that signed the Paper. The latter books are placed within the context of serious issues, honour killing in Kouri’s case and the tragedies faced by the people of Ukraine in the time of Hitler and Stalin. By their fabrication of tale both ladies diminished the agonies of those real life experiences (mostly untold) faced by some people in those settings. Tamil Tigress bears a similar potential.

In her interview with Margaret Throsby Niromi de Soyza said that she adopted this particular nom de plume in honour of Richard de Zoysa,[vii] a TV personality who was murdered by state agents during the Premadasa regime. We are told that she began writing the story 22 years ago, but only took it up again when adverse publicity emerged around the Tamil asylum-seekers arriving by boat at Australia’s shores from 2009. She considers her tale “unique” because she was a female fighter and a “child soldier” at that, albeit much like the many young Tamils who were ready to sacrifice their life for a just cause.[viii] Completing the tale, she adds, was “cathartic” for her. Thus, we could say that she presents herself as a driven force telling the world her truths.

Both in book and interviews we are told that she was a child of a love marriage between a Jaffna Tamil gentleman from the north and a lady from a merchant family from the Malaiyaha Tamil (that is Indian Tamil) peoples of the central regions of Lanka, a cross-community connection[ix] that created intra-familial tension according to her autobiographical account. This was a Catholic family, a sociological fact that is some consequence because of the type of schooling she received in Sri Lank and, subsequently, in India after she gained release from the LTTE’s ranks.

Whatever the verdict on the authenticity of the biography, Tamil Tigress is a captivating read. It is crafted with skill, with each chapter ending on a note of suspense or moment of change in her life world, so that the readers are brought in tantalising fashion to a threshold of change at the end of most chapters. All this occurs after a dramatic start where we face “The Ambush” in Chapter 1, an occasion when the neophyte teenage fighter Niromi receives a baptism of fire as her platoon is ambushed by enemy soldiers. Thereafter, de Soysa plunges her readers back in time by moving to her autobiographical family history and its various ethnic, intra-ethnic and caste tensions before bringing us back to her decision to join the LTTE and the events that followed. We are thrust back into the fight which launched the reading in “The Last Few Moments of Life” (Chapter 14) where her pal Ajanthi as well as platoon leader Muralie were killed. Thereafter we are taken through the events that moved her to extricate herself from the Tamil liberation struggle.

Through the characters in her life world de Zoysa cleverly speaks in different voices and conveys a complex body of political commentary that builds up a picture of a sturdy and resolute young woman who is alive to the faults on many sides, but stays firm in her dedication to the justice and cause of Eelam. She provides us with notable one-liners throughout her book: by way of illustration note these,

- “bottle up your anger and let it explode” through the mouth of Pirapaharan (24);

- “anyone who kills the voice of dissent is a tyrant” (49);

- “I am leaving my home so my people can have a homeland” – (her departing note to her mother – 69).

So, there is much that is stimulating in this vibrant tale.

Market Pitch, Fundamental Error

The dramatic beginning via “The Ambush” is geared to the book’s market pitch. Both the back cover and the cyber-world notices advertising the book tell us that “two days before Christmas 1987, at the age of 17, Niromi de Soyza found herself in an ambush as part of a small platoon of militant Tamil Tigers fighting the government forces that was to engulf Sri Lanka for decades (emphasis mine).”[x] The appeal here highlights the pathos of her journey in life by underlining her youthfulness and placing the encounter just prior to the natal day of Jesus Christ.

But within this little tale within a biographical tale lies a fundamental error. Once the uneasy relationship of ‘alliance’ between the LTTE and the Indian government (the LTTE’s ‘mentor’) unravelled in September-October 1987, the Tigers were engaged in a guerrilla war with the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) in the northern and eastern parts of the island. As the details below reveal, the armed services of the Sri Lankan state (GoSL) were not directly engaged in this war and did not have joint operations with the Indians on the ground. In brief, the December skirmish could NOT have been against Sri Lankan soldiers.

It is not an Allen & Unwin mistake. When de Soyza was interviewed by Margaret Throsby, she remarks “when I joined, the Indian forces had arrived and the Tigers had chosen to fight the Indian forces as well as the Sri Lankan forces.”[xi] Such profound ignorance suggests that she was not in Sri Lanka then and that her tale is a fabrication fashioned without adequate homework.

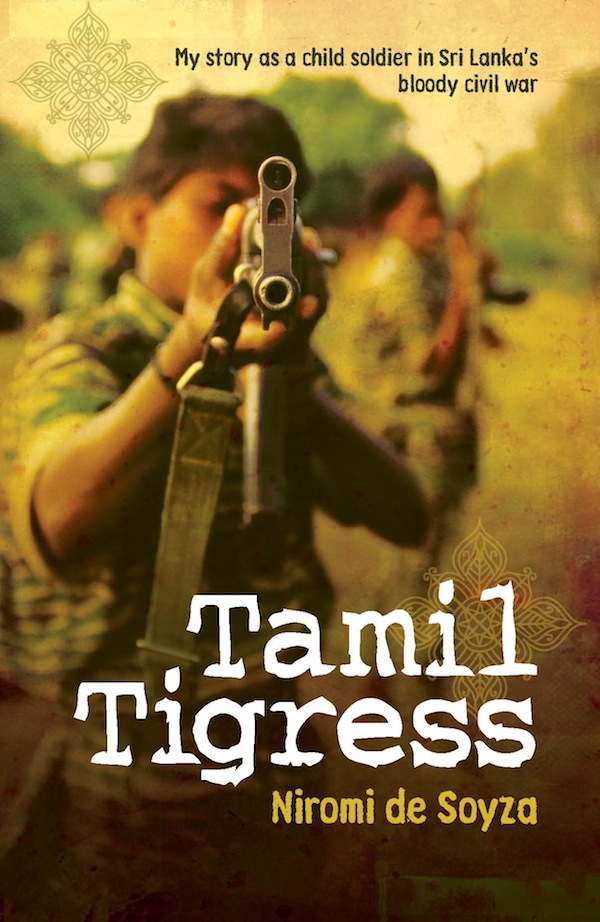

The sales appeal of Tamil Tigress, let me add, is accentuated by the presentation of photographs in one cluster in the middle. These include several of Tiger leaders and fighters. One photograph also depicts Muralie, the middle-level Tiger who features in “The Ambush.” His face is (perhaps conveniently?) obscured by the body of Amirthalngam Thileepan as the latter lay fasting on a platform beside the grounds of the revered Nallur Temple in Jaffna town during his protest against the intervention of the IPKF. This link is no accident. For one, both Muralie and Thileepan are said to have screened and finalised Niromi’s enlistment in the LTTE army. Secondly, and more vitally, Thileepan’s fast-unto-death occurred during a highly significant period for all the Tamil people of the north and east. Once war erupted in early October 1987 their main enemy became the IPKF, with the Sri Lankan state and the Sinhalese people receding into the background as the distant enemy (albeit the ultimate future enemy). For outsiders to comprehend this vital context, an outline history has to be inserted here.

Dramatic Shifts in the Year 1987

1987 opened with the LTTE firmly at the head of Tamil resistance to the Sri Lankan state after they had ruthlessly decimated the fighting capacity of two other militant Eelamist groups, TELO and EPRF.[xii] However, a major government offensive in May-June known as the “Vadamarachchi Operation” threatened the territories in the Jaffna Peninsula that were under LTTE control.

The Indian and Tamilnadu governments had participated actively in training all the Eelamist groups, with some 20,000 Tamil personnel receiving induction to warfare in India between August 1983 and 1987.[xiii] As this “investment’ was now threatened by the seeming success of the Sri Lankan state offensive, India flexed its military and diplomatic muscles in June 1987 to halt the suppression of the Eelamist movement.

In effect India browbeat Sri Lanka into accepting a dilution of its sovereignty by admitting Indian troops into the relevant parts of the island to “keep the peace.” Though motivated in part by a desire to protect the Tamil people, the principal goal in this intervention was the creation of a client state, thereby boosting India’s status as regional super-power.[xiv]

JR Jayewardene’s government accepted this imposition reluctantly. Its terms were embodied in what became known as the Indo-Lanka Accord. Rajiv Gandhi flew to Colombo to sign the accord on 29th July 1987. Indian troops comprising the “Indian Peace Keeping Force” flew into the Palaly airport in the Jaffna Peninsula even as the Accord was being signed. While violent protests erupted in the southern parts of the island, the IPKF personnel were greeted with rapture by most of the populace in the north.[xv]

Though the other militant Tamil groups welcomed the Accord, Pirapāharan had accepted the terms of the agreement “only as a temporary measure” in circumstances where he was under detention at the Ashok Hotel in Delhi.[xvi] Tiger personnel showed considerable belligerence during the first week of the IPKF’s imprint. When Pirapāharan was eventually brought back to the island by the Indians, he revealed his profound antipathy on several occasions to the disarmament enforced upon the LTTE by the agreement. This opposition as well as his ambivalence to the situation was evident to perceptive observers when he addressed a massive crowd of some 50,000 people at the grounds near the Sudumalai Amman Temple on the 4th August 1987. “We love India,” he said on the one hand, while other remarks expressed his opposition to the reduction of the LTTE’s clout in the northern parts of the country and the potential revival of militant Tamil rivals whom they had weakened by killing force in 1986/87.[xvii] In surmise one can also say that Pirapāharan was deeply embittered by the humiliations imposed upon him by the superior demeanour of Rajiv Gandhi and the other Indian “Brahmins”[xviii] in Delhi and the humiliation imposed upon the LTTE by the proposed removal of its main source of power, their weapons.

August-September 1987, therefore, was a period that saw political manoeuvres by the many parties in the political dispensation. In the east and the north these moves involved sporadic killings as the principal Tamil militant groups indulged in pre-emptive murders or reprisals at the local level.

The LTTE decided to turn the tide. Thileepan was their weapon of transformation.[xix] On 15th September he commenced his fast-unto-death. His progress to death was converted into a mass rally with his own speeches, music and fanfare working up the emotions of those around and then circulating along Tamil networks throughout the world. By the time he passed away on the 26th September, the tide of Tamil fervour for their cause under the LTTE banner had grown to tsunamic proportions.[xx]

At this point, early in October, the Sri Lankan Navy apprehended an LTTE boat making its way to India with 17 Tigers, including two senior commanders Kumarappa and Pulendran. As a political tug-a-war took place between the GoSL, the Indian powerbrokers in the island and the Tiger spokesmen, the simmering LTTE intentions of continuing their war of liberation came to the boil. The seventeen followed the leader’s command and swallowed cyanide pills that had been smuggled in by Anton Balasingham and Mahaththaya during the course of a prison visit.[xxi] This, then, became the casus belli and the final device to convince the Tamil people — its people in the LTTE conception — that the IPKF must be resisted.

Implications

The setting that I have traced above is pertinent to the embellishments in Tamil Tigress, notably the use of Thileepan’s photograph with Muralie beside him – both prominently highlighted in the book as the Tiger officers who enlisted Niromi (Tigress, 66-69), while Muralie was the platoon leader during her first experience of battle. These touches in turn provide a possible explanation for the reasons that induced de Soyza to obscure the fact that this fire-fight was against the IPKF. The alleged autobiography was finalized in 2010/11 in a context where the Western media has targeted Sri Lanka as an Ogre guilty of war crimes. To place Indian troops behind the guns that threatened her platoon would tarnish her goals.

These goals include an explicit desire to show Australians that the boat people who had begun to arrive off the coast of their continent were not economic refugees, but worthy asylum seekers fleeing persecution. She told Throsby that her tale was in line with the revelations provided by the Channel Four documentary Killing Fields and the Moon Panel of Experts. “I knew that when the Tamil Tigers were caught by the soldiers those things would happen they would be shot in the head, raped, tortured all of those things …It was nothing new.”[xxii] To complicate this propaganda pitch by placing the IPKF in the first chapter would spoil her intent.

While the government of Sri Lanka and its armies are her principal demon, de Soyza does not whitewash the LTTE. In line with the picture presented by the Panel of so-called “experts” commissioned by Ban Ki-Moon and The Cage by Gordon Weiss,[xxiii] some strictures are directed at the Tigers in both her final chapter “Afterwards” and her media interviews. As with Weiss’s line of attack, however, these criticisms are wholly overshadowed by the weight of condemnation directed at Sri Lankan state and society.

Thus, the concluding pages are straight out of the propaganda package drafted by the Global Tamil Forum that has become part of the hardened beliefs of a whole spectrum of migrant Tamils in their condition of emotional turmoil and desire for retribution. Some statements, such as the note that “journalists and politicians – both Sinhala and Tamil—have become victims of government thuggery,” carry some validity;[xxiv] but others are misleading. For someone in late 2010 or early 2011 to state that “some 100,000 Tamils displaced by the war … were held against their will in behind concentration camps where they endure primitive conditions” (Tigress, 303) and to assert that “Sri Lanka remains a very dangerous place not only for Tamils but for anyone who openly criticises the government’s anti-democratic stance” (Tigress, 303) is a combination of malicious slander and exaggeration.[xxv]

Similar criticisms were voiced in her chat with Throsby. Sri Lanka today is a place permeated by “silence” because “there is no free speech” and “the Tamils are continuously oppressed.” Such opinions are no doubt firmly held in several Tamil quarters in Australia and elsewhere. The work of the Tamil spokespersons worldwide has also convinced many educated persons in the West – to the point where Margaret Thorsby tells her listeners that during the last stages of the war in 2009 “40,000 civilians might have been massacred.”

Perhaps it is too much to expect Western media persons to seek more solid empirical information by consulting Tamil personnel in Australia and Sri Lanka with some knowledge of conditions in Sri Lanka as they have moved over time. My brief visit to Vavuniya and Jaffna in June 2010 was an eye-opener.[xxvi] The welfare work undertaken by such NGO’s as SEED, Sewalanka, Caritas, et cetera in both the IDP camps and the northern reaches should be a lesson in humility for those, like me, who live by pen rather than deed. If only people like Margaret Throsby and Philip Adams would consult such persons as Singham, Annet Royce, Thamilalagan and Kesavan (all Tamils by the way) out there delivering aid in the countryside in the north-east, rather than relying on NGOs cloistered in Colombo or embittered migrant spokespersons for their “facts,” Sri Lanka could move forward. They would, for instance, find that Niromi de Zoyza’s picture of the IDP camps was largely a figment of the imagination. Those outsiders with honest intent are well advised to read Rajasingham Narendran’s overview of the Tamil IDPs based on interviews and visits among them when they were in transit at the rear of the battlefront in early 2009 and subsequently after unmonitored visits to some camps in the middle of that year.[xxvii]

As it happens, I have received an unsolicited note from a Lankan Australia who has just returned from aid work he has been directing in Mannar District. Jeremy Liyanage’s report was succinct: we “ran five focus groups — four with Tamils and one with Muslims, all in Mannar. The story is now consistent over three separate periods of interviews over the past 12 months, that people are conflict saturated, that they don’t want the Tamil diaspora to speak on their behalf, that the Eelam project is a failed project, and that they want a united single Sri Lanka but with conditions (equality of opportunity and outcome).”[xxviii] This concise assessment, I stress, is for one district and should not be blindly extended to the Tamil people in other localities. It is nevertheless a suggestive pointer for the northern regions in general.

Trivial Errors? Ethnographic Howlers of Profound Import?

While it was the foundational error in describing the context of her first battle experience that raised questions in my mind about the authenticity of de Soyza’s autobiography, there are other tell-tale signs that added to these doubts – as I have remarked in my initial essay on this topic.[xxix] These were minutiae. Again, a range of minute points of error are listed by Arun Ambalavanar when he recently made the suggestion that Tamil Tigress was a “farce.”[xxx]

From recent email exchanges I gather that personnel in publishing circles in Australia treat such details as silly attention to trivia. The support for Tamil Tigress by such gentlemen as Gordon Weiss[xxxi] would seem to have been adequate ground for them to dismiss Ambalavanar’s questions as ill-founded.[xxxii] Such evaluations say a great deal about the mentality and background knowledge of Australian publishing houses. As such, one has a tangential issue that is also worth reflecting upon.

Australian publishers, and Allen and Unwin in particular, would do well to remember how Random House rejected the Jordanian protests initially – till they learned the hard way. Like the Jordanians, Ambalavanar represents an indigenous Jaffna Tamil voice. True, there is some nit-picking within his array of doubts. However, it is the cumulative implications of such “trivia” that weigh heavily against Niromi de Soyza.

Some of the questions from Ambalavanar which the publishers may regard as trivial objections have the character of “ethnographic queries” in an anthropological sense. Ambalavanar is not only a native, but a Tamil poet. He distils his allegations neatly when he says that the narrative in Tami Tigress bears a fake “accent.” When Ambalavanar tells us that the Tamil equivalents of such terms as “motherfucker” “fuck” and “boy friend” were not widely used in 1980s Jaffna, yet feature several times in Tamil Tigress, anyone with a nose for context should have paid attention to his claims.

Even though de Soyza’s main political pitch is directed against the Sri Lankan government, Tamils who are guided by their “Tamil-ness” as well as those who are Tamil-Tiger in ideology should be cautious about mounting her bandwagon. They could ask the question: “how would talaivar Pirapāharan have responded to her book?” They should then link this to a second question: “would Niromi de Soyza have written such a book if he was still alive?”

That second question would be akin to the placement of a panther in de Soyza’s bedroom. Her tale has Pirapāharan visiting her training camp at one point (Tigress, 159-60) and the great leader tasking her with the job of purchasing female Tiger clothes from a secure house at another point (Tigress, 167). Pirapāharan alive would obviously be quick to differentiate tall tale from fact. Pirapāharan alive would also react ruthlessly against any Tamil who smeared the gravity of the Tamil movement for independence with tall tales.

Concluding Remarks

Though I have not reached a definitive verdict on the issue of fabrication, my leanings are strongly in that direction. Niromi de Soyza’s answer to any such charge is within easy reach. There is no earthly reason why she cannot reveal her identity. Her assertion in interviews that “her personal safety” would be endangered is just so much nonsense, a massive conceit. Where Australians buy this argument, they only reveal their simple-minded thinking and the degree of indoctrination they have absorbed from the propaganda juggernaut of Tiger International.[xxxiii]

For one, both Tamil Tigress and The Cage are on sale in Sri Lanka. For another there is no reason why the government of Sri Lanka would target an ordinary Tiger soldier from way back in time when they had detained around 11,500 Tigers in their high security centres in mid-2009 and have since released about 8500 after what they term “rehabilitation,”[xxxiv] whatever that means. Again, the likelihood of some Sinhala Australian chauvinist intimidating de Soyza through phone calls is remote and should hardly be intolerable for a committed Tamil nationalist. If Noel Nadesan could withstand these forms of intimidation from ardent Tiger supporters in Melbourne for 13 years because his moderate stance and his editions of Uthayam angered them, there is no reason for this lady to hide behind anonymity.

In any event there is a second alternative. All de Soyza has to do is to release the real names of Ajanthi and Muralie, both long dead (and thus reborn). Those with access to the lists of Tiger māvīrar (heroes, ‘martyrs’) and their dates of death would tell us whether they existed in body and plane. Niromi de Soyza would then be vindicated.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ambalavanar, Arun 2011 “The Farce of a Fake Tigress,” http://www.srilankaguardian.org/2011/08 / farce-of-fake-tigress.html.

Blacker, David 2011 “The Holes in the Darusman Defence — Examining the Probable Events,” http://blacklightarrow.wordpress.com/2011/07/25/2064/

De Votta, Neil 2004 Blowback. Linguistic Nationalism, Institutional Decay and Ethnic Conflict in Sri Lanka, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Gunaratna, Rohan 1987 War and Peace in Sri Lanka: With a Post-Accord Report From Jaffna, Kandy, Institute of Fundamental Studies.

Gunaratna, Rohan 1993 Indian Intervention in Sri Lanka: The Role of India’s Intelligence Agencies, Colombo, South Asian Network on Conflict Research.

Gunatilleke, Godfrey 2011 “Truth and Accountability: The Last Stages of the War in Sri Lanka,” http://www.margasrilanka.org/Truth-Accountability.pdf

Hoole, Rajan 2001 Sri Lanka: the Arrogance of Power. Myths, Decadence and Murder, Colombo: Wasala Publications for the UTHR.

Jeyaraj, D. B. S. 2006 “No Public Speech Ceremony for LTTE Chief This Year?” 26 November 2006, http://dbsjeyaraj.com/dbs/archives/650.

Jeyaraj, D. B. S. 2009d “Pottu Amman and the Intelligence Division of the LTTE,” 11 Sept. 2009, www. transcurrents.com

Jeyaraj, D. B. S. 2009 “Wretched of the Earth break free of Bondage,” Daily Mirror, 25 April 2009.

Knox, Malcolm 2005 “The Darville made me do it,” Sydney Morning Herald, 9 July 2005.

Narayan Swamy, M. R. 1994 Tigers of Sri Lanka, Delhi: Konark Publishers Pvt Ltd.

Narayan Swamy, M. R. 2003 Inside an elusive mind. Prabhakaran, Colombo: Vijitha Yapa Publications. de Silva, K. M. 1993 “The Making of the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord: The Final Phase, June-July 1987,” in KM de Silva & SWR de A Samarasinghe (1993) Peace Accords and Ethnic Conflict, London, Pinter Publishers, pp. 112-155.

Narendran, R. 2009 “Internally Displaced Persons: The New Front of an Olld War,” http://trans currents. com/tc/2009/08/post_415.html.

Roberts, Michael 2006a “Pragmatic Action and Enchanted Worlds: A Black Tiger Rite of Commemoration,” Social Analysis 50: 73-102.

Roberts, Michael 2006b “The Tamil Movement for Eelam,” E-Bulletin of the International Sociological Association No. 4, July 2006, pp. 12-24

Roberts, Michael 2007“Blunders in Tigerland: Pape’s Muddles on ‘Suicide Bombers’ in Sri Lanka,” Online publication within series known as Heidelberg Papers in South Asian and Comparative Politics (HPSACP), ISSN: 1617-5069.

Roberts, Michael 2008 “Split Asunder: Four Nations in Sri Lanka,” www.groundviews.org, 13 January 2008.

Roberts, Michael 2009 “Dilemma’s At War’s End: Thoughts on Hard Realities,” www. groundviews.org, 10 Feb. 2009 and Island, 11 Feb. 2009.

Roberts, Michael 2009 ‘The Needs of the Hour,” www.groundviews.org www.groundviews.org, 1 April 2009.

Roberts, Michael 2009 “Some Pillars for Lanka’s Future,” Frontline, 19 June 2009, 26/2: 24-28.

Roberts, Michael 2009 “The Rajapaksa Regime and the Fourth Estate,” in www. groundviews. org, 8 December 2009.

Roberts, Michael 2010 “Killing Rajiv Gandhi: Dhanu’s Sacrificial Metamorphosis in Death?” South Asian History and Culture 1: 25-41.

Roberts, Michael 2010 “Aussies swallow lies & Rajapakses miss a trick,” www.thuppahi. wordpress.com, 31 Oct. 2010.

Roberts, Michael 2010 “Omanthai! Omanthai! Succour for the Tamil Thousands,” in http:// transcurrents. com/tc/2010/08/omanthai_omanthai_succour_for.html.

Roberts, Michael 2011 “A Think-Piece drafted in May 2011,” http://thuppahi.wordpress. com/ 2011/07/23/a think-piece-drafted-in-may/#more-2998.

Roberts, Michael 2011 “People of Righteousness target Sri Lanka,” http://thuppahi. wordpress.com /2011/06/27/people-of-righteousness-target-sri-lanka/

Roberts, Michael 2011 “Another Demidenko? Niromi de Soyza as a Tiger Fighter,” http:// thuppahi.wordpress.com/2011/08/21/another-demidenko-niromi-de-soyza-as-a-tiger-fighter/

Samarasinghe, S. W. R. de A. & Kamala Liyanage 1993 “Friends and Foes of the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord,” in KM de Silva & SWR de A Samarasinghe (1993) Peace Accords and Ethnic Conflict, London, Pinter Publishers, pp. 156-172.

Tekwani, Shyam 2011 “The long afterlife of war in teardrop isle,”http://tehelka.com/ story_main50.asp?filename=Ws290811long.asp

[i] See her clarification of the factors that moved her to pen this work: http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=FikCt-dimkE.

[ii] http://listverse.com/2010/03/06/top-10-infamous-fake-memoirs/

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Malcolm Knox, “The Darville made me do it,” Ibid.

[vi] “As a result of her discussions with Allen & Unwin, the author changed the names in the book from “Demidenko” to “Kovalenko” and also altered her author’s note to say: “What follows is a work of fiction. The Kovalenko family depicted in this novel has no counterpart in reality” (Malcolm Knox, “The Darville made me do it,” in the Sydney Morning Herald, 9 July 2005 – see http://www.smh.com.au/news/books/the-darville-made-me-do-it/2005/07/08/1120704550613.html.

[vii]Sinhala is phonetic and the name “de Zoysa” would be spelt in the same way as “de Soysa’, but the rise of English enabled families to distinguish their lineage through different spelling. “De Soysa” usually denotes people from the Karāva or Durāva caste, while “De Zoysa” usually indicates someone from the Salāgama caste [with the s or z in the ending being interchangeable].[viii] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FikCt-dimkE.

[ix] When the author describes this link as “a mixed race family” (http://www.youtube. com/watch?v=FikCt-dimkE), she adopts the loose use of the term “race” that is so common in India and Sri Lanka; but she also separates two bodies of people who have strong linguistic affinities and are widely regarded as being an interlinked ethnic group.

[x] This is part of the blurb on the back cover of the book as well as notices on web presented by the publishers Allen and Unwin (see http://books.google.com/books/about/Tamil_Tigress. html?id=XQdukyYkdBcC).

[xi] http://www.abc.net.au/classic/throsby/2011_07.htm.

[xii] To de Soyza’s credit, she refers to these actions of the LTTE (Tigress, 48-52).

[xiii] Information from Rohan Gunaratna , tel. chat, 25 August 2011. Also see Gunaratna 1993; Narayan Swamy 1993.

[xiv] See KM de Silva 1993; SWRde A Samarasinghe & Kamala Liyanage 1993; and Gunaratna 1993.

[xv] Narayan Swamy 1993: 247-48 and Tamil Tigress, 85ff.

[xvi] Narayan Swamy 1993: 244.

[xvii] Narayan Swamy 1993: 250-53. I have also profited from accounts of this momentous event from the venerable Indian journalist, PK Balachandran, in Colombo and from Daya Somasundaram in Adelaide.

[xviii] “Brahmins” is used metaphorically here to characterize the bearing of many North Indian politicians and officials in relation to people of lesser states or people from the countryside.

[xix] Thileepan carried a debilitating injury. He was also a LTTE theoretician, one with a total commitment to the cause of Eelam.

[xx] Narayan Swamy 1993: 250-53.

[xxi] In Tamil Tigress this act is attributed to Roshan, the author’s ‘boy friend.’ There is a marked propensity in de Zoyza’s story for significant events to be linked to her circle of acquaintances. Again, Pirapaharan Thileepan, Kittu and Mahaththaya, the highest in the Tiger hierarchy, every one of them, comes into touch with de Soyza in one way or another. This is truly remarkable. How it DID NOT arouse Allen & Unwin’s suspicions is as remarkable.

[xxii] http://www.abc.net.au/classic/throsby/2011_07.htm.

[xxiii] The Moon Panel’s report is both shoddy and deeply flawed; and the analytical poverty of those who deploy it raises serious questions about their capacities. For careful assessments, see Blacker 2011 and Gunatilleke 2011. Also note Tekwani 2011 and Roberts, “A Think-Piece drafted in May 2011.”

[xxiv] See http://jdsrilanka.blogspot.com/2009/08/sri-lanka-thirty-four-journalists-media.html and

http://www.bbc.co.uk/sinhala/news/story/2009/07/090722_jds_journalists.shtml; and also Roberts, “The Rajapaksa Regime and the Fourth Estate,” in www.groundviews.org, 8 December 2009.

[xxv] For info on the topic of IDP camps, see R. Narendran, “Internally displaced persons: a new front in an old war,” http://transcurrents.com/tc/2009/08/post_415.html and M. Roberts, “Aussies swallow lies & Rajapakses miss a trick,” www.thuppahi.wordpress.com, 31 Oct. 2010.

[xxvi] Roberts, “Omanthai! Omanthai! Succour for the Tamil Thousands,” in http://transcurrents. com/tc/2010/08/omanthai_omanthai_succour_for.html and Roberts, “Aussies swallow lies and Rajapaksas miss a trick,” in http://thuppahi.wordpress.com/2010/10/31/aussies-swallow-lies-rajapakses-miss-a-trick/.

[xxvii] Narendran, “Internally displaced Persons: The new front of an old war,” http://transcurrents. com/tc/2009/08/post_415.html. They will have to discount the typical intimation from Tamil propagandists who allege that there was “show camp” for distinguished visitors. Also note DBS Jeyaraj on “The Wretched of the Earth break Free of Bondage,” 2009.

[xxviii] Email dated 20 August 2011. Liyanage is of Sinhala-Burgher mix and is Australian educated. He is a key figure in the cross-ethnic group called Diaspora Lanka Ltd which runs the welfare work in Mannar.

[xxix] Roberts, “Another Demidenko? Niromi de Soyza as a Tiger Fighter,” http://thuppahi.wordpress. com/2011/08/21/another-demidenko-niromi-de-soyza-as-a-tiger-fighter/

[xxx]Ambalavanar, “The Farce of a Fake Tigress,” http://www.srilankaguardian.org/2011/08/ farce-of-fake-tigress.html).

[xxxi] See “FUTURA BOOK NIGHT – Gordon Weiss and Niromi de Soyza,” in http://www.facebook. com/event.php?eid=137919256296979 and the notice re Niromi’s “amazing autobiography” in the Weiss website (http://www.gordonweissauthor.com/links.html). Re Weiss’s dubious presentations, see Tekwani 2011 and Roberts 2011.

[xxxii] This comment is based on email communications from Meera Govil, Nikki Baraclough and Arun Ambalavanar in August 2011.

[xxxiii] Today, the intricate network of LTTE personnel that exists world wide has been bolstered by two streams: (A) second and third generation migrants who were drawn into the LTTE cause by their Tamil-ness during the fervent emotions aroused by the demise of the LTTE as a military force in Lanka and (B) the entry into Australia, Canada and elsewhere in recent years of hardline Tigers who mingled with the civilians who reached IDP camps and then slipped out with the aid of bribes and local networks (information from M. Sarvananthan, interview, 6 November 2010 and S. De Silva Ranasinghe, “Exclusive interview with T. Sridharan,” South Asia Defence & Strategic Review, Sept-Oct 2010, p. 47). Grapevine information from Tamil sources in Australia indicates that some of these personnel are stirring the pot in both asylum centres and Tamil community circles in the main cities of Australia (sources withheld).

[xxxiv] Dr Safras to Roberts: “Initially there were almost 11,500 and out of all more than 8000 are rehabilitated and reintegrated, more than 2500 are presently undergoing rehabilitation” (email 29 August 2011).

###

Long Reads brings to Groundviews long-form journalism found in publications such as Foreign Policy, The New Yorker and the New York Times. This section, inspired by Longreads, offers more in-depth deliberation on key issues covered on Groundviews.