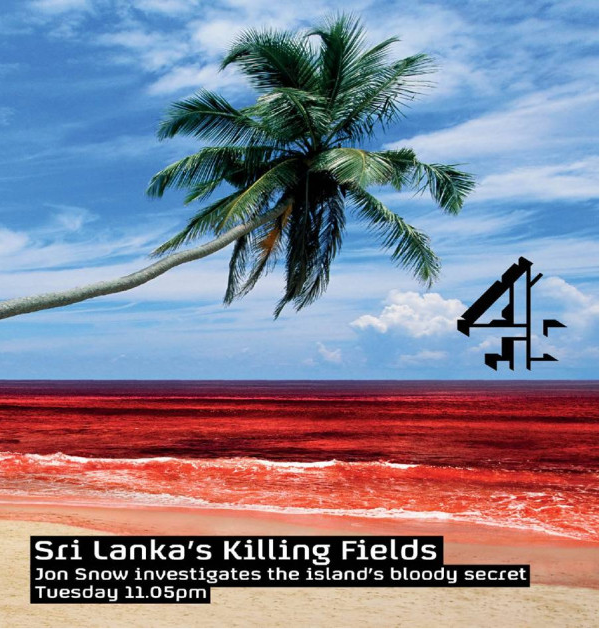

It was the most gruesome of visual feasts and it when it ended, the most disorienting sense followed. One is struck, not by the extremity of human suffering; but by stillness, by the insouciance of the pools of blood. They appear on screen as almost as if they are the everyday aftermath of one of the island’s heavier monsoon rains. Excepting, of course, the fact that happy children do not float paper boats in these pools, nor is the water that comfortable colour of milky tea. The children are dead; the water runs red with blood. And it is simply, understatedly there.

“Sri Lanka’s Killing Fields” is a damning indictment of the various parties involved in the last few months of the civil war. It must be watched critically, and to do so, it is necessary to separate Jon Snow’s narration and open your eyes to the story that you must yourself piece together. Image upon images plays towards you, reminiscent of Goya’s exceptional set of prints “Disasters of War”. Then an illustration of the brutality of the Napoleonic Wars, it now feels like an incredible case of precognition. War is brutal; our modern sensibilities, created in the aftermath of a bloody Reformation and a succession of world and civil wars accept this fact as part of our cognitive DNA. As creatures of such knowledge structuring, it is unremarkable that, in the final analysis, we are somehow able to excuse the existence of the dead. In ‘Killing Fields’, however, it is not the high rate of death that overwhelms you, it is the ease with which life loses its value. It becomes nothing to the SLA forces leering gleefully over the bodies of dead cadres; to the LTTE leadership who gunned down their own in the final struggle for Eelam; to the frontline doctors fighting a losing battle; to the thousands of Tamil civilians themselves, as they surrendered to attack from one side and betrayal by the other.

Channel 4 is to be commended for airing a documentary which provides a great degree of visual confirmation of the atrocities that occurred during the final months of physical hostilities between the Rajapaksa Government and the LTTE. While the story told is emotionally and mentally distressing, the first thirty minutes do not raise issues that those who followed the army‘s advances closely were not aware of. Within these several minutes, we are provided with detail of the SLA’s march upon LTTE territory, and the latter’s increasing struggle to hold its ground. Caught between the two, are the tens of thousands of Tamil civilians, sandwiched into increasingly small pockets of land. Reports of the thousands trapped and dying in Putthukidyrippu, Mullaivaikul, and the infamous No Fire Zones reached the ears of Sri Lanka’s local and internationally led civil society via the text messages and communications from priests, nuns and Tamil NGO personnel trapped within these areas. As the documentary confirms, the Tamil government doctors were in constant communication with the ICRC and the GoSL medical authorities as they requested aid and supplies. To their credit, various organisations attempted to make the local and international public aware of the rising numbers of the dead, and insisted on asking hard-hitting questions from all parties said to be ‘responsible’ for the high civilian count. These reports provided facts about the scale and the magnitude of death, but the human face of the civilian that was missing.

Reports typed up by NGOs and International bodies are often factsheets that proclaim statistics- and statistics are open to interpretation and easily dismissed- academics, politicians and policy makers do this every day. It is the visceral emotion of a grown woman moaning “Amma; it was from this hand that you fed me” that provides the jolt to your consciousness. Arguably, media today is well versed in the art of emotional manipulation and the Channel 4 documentary quite consciously imposes each image and story upon you in a sequence that deliberately wishes to evoke the maximum effect. The camera freeze frames on the bodies of babies, and children. A hospital administrator is shown being interviewed one moment; still and dead the next. The primary eyewitness story is from an attractive young woman. They are, perhaps, overused devices. It is imperative for the viewer to separate the production of the narrative from its external trappings. Yet, even with such ‘deconstruction’, you will still find that the videos and photographs speak entirely for themselves, and that your final conclusions are grim ones.

Visuals are a more effective method of concretising truth. Images of the LTTE’s attacks on public areas , and the subsequent broken bodies littering the streets of Colombo and Kandy cities confirmed the ruthlessness of the ‘Tigers’ in their struggle for Eelam. The LTTE deliberately used Tamil civilians as a human shield during the last few months of physical hostilities against the Sri Lankan government. They also funded their struggle through both legal and illegitimate concerns; grocery stores in Western suburbs and international heroin trafficking rings. Perhaps in strategy, the LTTE moved far and away from the nobility of a battle for self-determination and equality; but it is impossible not to consider that, in the face of the Sinhala chauvinism that made the national agenda in early postcolonial years, there was no path to follow but one that was volatile, ceaseless and increasingly violent. It should not be forgotten, as the new narratives being written in post-conflict Sri Lanka are attempting to do, that the LTTE’s eventually disastrous acts were political entrapment engendered by the harshness of the Sinhala Raj; they were freedom fighters once. The narratives created post-conflict are dangerous and must be interrupted, as the entrapment of the conflict by discourse is also responsible for its eventual end.

During the officially recognised thirty year period when the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam fought the forces of the Government of Sri Lanka, the developments of the conflict came to mirror and link themselves with several external phenomena being played out in the international sphere. Specific ideas of freedom, equality and human rights; discourses which were made concrete and hegemonic in the years following the Cold War were thrown into the language of the Tamil freedom struggle, but also framed the general logic for the GoSL in its approach to seeking international succour. The ‘war’ absorbed other discourses as it, unwittingly, moved with the course of history. The regime of George.W.Bush, for example, switched Velupillai Prabhakaran’s label effectively from guerrilla leader to terrorist; and as America solidified the rhetoric of the ‘Global War on Terror’, the GoSL was lent legitimacy for its final, devastating advance upon the depleted ranks of the LTTE, ending physical hostilities in the summer of 2009, and, in the words of exultant commentators worldwide, ending Sri Lanka’s ‘terrorist problem’. Significantly, the LTTE were pioneered and refined the art of suicide; a method of attack that would prove important during the events of September 11th. Many observers note that the end to the war in Sri Lanka was a result of a more superior army, the possession of efficient fighting tools, the ruthlessness of the new army leadership and, more often than not, the regime of the Sonia Gandhi-led Congress party in India. A less positivist driven argument would be to consider that the ability of the Sri Lankan government to make the final push; and to eviscerate the LTTE leadership in the manner that they did was made possible because the defeat of terrorism and the death of a terrorist had by then become a valid part of the moral fabric of modern discourse. The image of the lifeless Prabhakaran, shown widely on the international news in a manner that recalled Achilles’ ransoming of the body of Hector, was met with an abundance of joy and relief. Almost two years later, the same fate would await Osama Bin Laden- sans the public display. The importance of the example is this; discourse and knowledge authorizes the morality of what were, in both cases, extra judicial murders. The manner of both executions were made possible because the death of a terrorist, a figure impossible to view from any other lens as a feared ‘Other’, has become a moral ‘good’.

The LTTE’s own activities in the extra-judicial world lent credence to such labelling, and there is no moral court in any system or society that will be able to easily exonerate such crimes. However, as Sanjana Hattotuwa notes in his review of Gordon Weiss’ The Cage (incidentally a tome that reads very much as the book of this film) therein lies the rub, there is no one left of the LTTE leadership to be held accountable. The bodies of several of the senior leadership were last seen lying, stripped, tortured and summarily executed on the very land they fought to claim. In a most macabre way, some of the many photographs and news clips of the dead Prabhakaran show members of the SLA posing for a group shot alongside the corpse. In one memorable news clip ( not shown in the documentary) there was even the whooping and raucous Sinhala commentary of an ITV presenter; a man whose lack of professionalism was only matched by his undoubtedly diminutive wit.

While this presenter is certainly an excellent representation of the status quo that Sri Lanka has slid toward under the guidance of Mahinda and his Merry Men, his behaviour is overshadowed by the crudity of the SLA personnel we see in the last fifteen minutes of ‘Killing Fields’? Leers, vulgarisms and chauvinistic bravado abound as female cadres are thrown like dead cattle into the back of a truck and bound and gagged young men are executed in cold blood. This is not the behaviour of glorious war heroes, but the hysterical and brutish violence that has been engendered by the Rajapaksa regime. In a style of execution that violates any subscription to judicial proceedings or necessary war tribunal, these soldiers- undoubtedly with permission from their Generals and the powers that be- have taken matters into their own hands. Not only the LTTE leadership easily identified in these images, but seemingly any person singled out as a ‘Kotiya’, were murdered, and a photograph taken for posterity; SLA forces pose with their trophies as if displaying a fascinating curio bought during a particularly exotic holiday. The inhumanity of the military personnel is shocking. Aren’t these supposed to be ‘our boys’, fighting an ‘enemy’ that threatened the bedrock of our national ‘peace’? Admittedly, Weiss’ book and the C4 documentary note the compassion of many SLA soldiers, moved by the plight of the civilians they met, sharing their military rations and assisting women and children to safety. Many of these personnel; ranking officials and regular soldiers alike turned a blind eye when internees at IDP camps attempted escape. Weiss notes the story of a staff officer who unlocked the gates of the enclosure he supervised and encouraged people to leave. Such actions are remarkable; not because they were made in the heat of war but because many of these soldiers were Sinhala persons hailing from the deep South; a place in which a number of individuals you encounter will confess to having had little or no familiarity with their Tamil ‘Other’. Such Samaritan like actions are, unfortunately, countered by the cold blooded executions carried out by their colleagues and what is the undeniably deliberate genocide orchestrated by the Rajapaksa government.

Genocide is a strong word and usually reserved for Rwanda, Serbia, and other incidents where the world has sanctioned the fact that horrendous crimes took place. It is perhaps not incorrect to use it here. Perhaps in their removal of their own staff from the conflict area, and their continued vague silence on the ‘Sri Lanka’ issue, the UN itself has sanctioned the mass genocide that occurred in the last few months of Sri Lanka’s war? The Channel 4 documentary is quite insistent in pointing the finger of blame at the UN; saying that it did not do enough- and that, even after the Darusman Report, it continues an eerie disengagement with regards to Sri Lanka. Ban- Ki Moon is shown happily walking through an IDP camp on a whistle stop tour; he did not stop to allow himself to see what really happened. Moon and the international community have been, oddly, unable to bring any real pressure on the GoSL. The placing of blame on the UN, while quite correct within the situation is also, obviously bound up in Western hysteria regarding the growing strength of China and other non-Western powers. Moon’s strange inactivity will be ( and is) called into question, and China’s own activity on the UNSC builds not so much an anti-UN case but the usual refrain of Western commentators warning us of the dangers of allowing the international predominance of an ‘Other’. It is important to acknowledge the argument, but equally necessary to dismiss the hegemony of its discourse.

To place blame on the UN also further distances us from the accountability of the GoSL, and we will stop seeing them as significantly responsible. It also provides for the blossoming of a rather spurious counter argument from the GoSL’s favourite talking heads, Dayan Jayatilleka and Rajiva Wijesinha, who are manipulating a nuance of the thinking on hegemonic discourse to build a rude counter-rhetoric of ‘us’ versus ‘them’- spinning the image of the GoSL as the innocent victim of a Western conspiracy. It is, very simply, blatant exploitation of the oft dragged out colonizer/colonized dichotomy that both gentlemen have also managed to conflate with a similar dialectic that existed during the Cold War. To do so indicates a desperate scrabble to hide the truth behind a tissue of easily dismissible arguments, and to do a rather serious disservice to the complexities of the post-colonial analysis and the theoretical discussion of alterity. Further to this, various members of the international community have been vocal but inactive with regards to the Sri Lankan conflict- damning neither the GoSL’s sixty years of state –led violence or the extra-legal activities that the LTTE leadership indulged in for three decades, that the UN continues in this vein is, in the final analysis, hardly remarkable.

The most eerie moment in the documentary is a sequence in which Gotabhaya greets his brother Mahinda. The two men, smile, nod and acknowledge each other- the look that passes between the two of them speaks volumes and one cannot but wonder. Gotabhaya’s guilt is palpable in the hysteria he brings to any non-Rupavahini interview. To return to the point on genocide- as ‘Killing Fields’, The Cage, and several others have pointed out, the evidence of eyewitnesses, doctors, the UN and other non-governmental personnel make it abundantly clear that the SLA leadership was quite aware that when it sent fire and dropped shells into certain areas, they were clearly killing civilians as much as they were LTTE cadres. The ICRC, in fact, handed them bodies on a plate when it broadcast the coordinates of the various frontline hospitals. The government issued its own coordinates for a No Fire Zone, and as the testimony of Brig. Harun Khan demonstrates, fired directly into it. Like the schoolgirls at Sencholai, civilian deaths are dismissed in this easy manner; they must all be ‘Koti’. We know they were not. Such labelling by the government is a thin excuse for the deliberate genocide that led to the deaths of thousands of innocent Tamil civilians. The LTTE murdered some as part of their guerrilla warfare and cynical strategy; but the SLA and the Rajapakse government murdered civilians because they were, simply, Tamil. This is genocide for it was obviously deliberate and moreover because it was a race crime; intending to obliterate as many Tamil persons as possible, subsuming action under the blanket of the ‘fog of war’. Why else remove the witnesses from the media and the UN, unless you wanted to clear the scene for a premeditated crime? This, overall is the question that the C4 documentary, Weiss’ book and other voices, many of whom have been featured here on Groundviews, have raised. It is a question that we must not stop asking the Rajapaksa’s. Surely, Mahinda Rajapaksa, lawyer and vociferous campaigner for human rights, knew quite well the crime he was about to become party to?

The Channel 4 documentary misses a fourth, and equally complicit party. To lay a j’accuse here is difficult but necessary. The Sinhala public, in Colombo and Kandy and other cities have always known, on some level, of the atrocities carried out by successive Sri Lankan governments, and the Rajapaksa’s in particular. The LTTE abducted little boys from school and made them cadres; the Rajapaksa government accosts journalists on the streets and makes them cadavers or exiles. Young Tamil men are abducted too; Sri Lankans live in a society where true freedom of speech is a fond and mostly forgotten memory, and where a 21 year old lost his life when protesting for his simple right to a fairer pension. We are all, this author included, complicit in this genocide and we must be held accountable because we have preferred to remain silent and un-dissenting. With the exception of a few voices, we have shook our heads and simply accepted what this government and its predecessors have done; we have either been as vaguely inactive as the UN and the international community or we have not done enough. In this way, we have lent and continue to give succour to mass genocide and a future of oppression. The Channel 4 documentary and the roused international middle classes will, for the short time that it holds their interest, ask the UN, David Cameron and Barack Obama to intervene; will ask them what they are going to do about Sri Lanka. It is necessary to ask the Sinhalese – and their middle classes in particular- what will you do? The evidence is mounting; will you remain silent and inactive yet again? It is time that head shaking and the bearing of witness was translated into real action. Free yourselves from the bounds of that modern instinct that asks you to preserve yourself and your society; and look to a struggle that can truly initiate a just and free society.