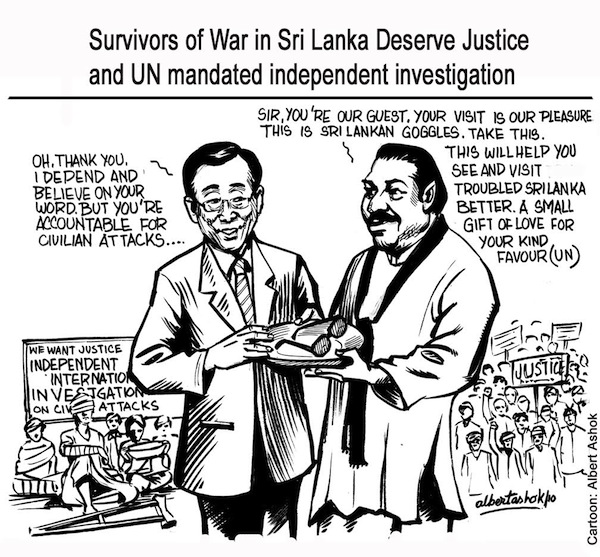

Cartoon by Albert Ashok

As conflict raged, the United Nations Commissioner for Human Rights had stern words for those on both sides. “All violations of international humanitarian law and human rights law must be investigated and those responsible for breaches – including deliberate targeting of civilians, indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks, the killing of injured persons and the use of human shields – must be brought to justice,” her spokesman told reporters.

The year was 2004, and fighting in Fallujah in Iraq was taking an ongoing toll on ordinary people. The UN Commission on Human Rights special rapporteur on the right to health had earlier listed “extremely serious allegations” against the US-led coalition that had taken control of Iraq and called for an independent inquiry.

UN investigators continued to keep a close watch on Iraq. Just last year, special rapporteur on torture Manfred Nowak – who in 2006 had condemned the US detention centre in Guantanamo Bay as a “torture camp” – urged President Barack Obama to investigate US forces’ complicity in torture in Iraq.

Political wheeling and dealing affects the UN’s ability to take action on human rights abuses. Nevertheless, many of its officials are experienced in cutting through the lies and evasions of governments to uncover what happens in conflict zones. Numerous states – including the US and other Western powers – have been challenged over human rights abuses.

Human rights organisations such as Amnesty International have been unsparing in challenging governments and rebel forces across the world over human rights violations. In March 2003, as the US-led coalition went to war in Iraq, AI warned that “”Those who have launched the military attacks must take responsibility if their action provokes a human rights and humanitarian catastrophe.” In April, AI condemned the coalition’s use of weaponry that caused excessive civilian casualties, in no uncertain terms: “The use of cluster bombs in an attack on a civilian area of al-Hilla constitutes an indiscriminate attack and a grave violation of international humanitarian law.”

The mistreatment of detainees too was soundly condemned by AI. It was not only international organisations which raised the alarm about abuses – the media also played a part, including those in the USA. While some swallowed their government’s propaganda, others were willing to expose its misdeeds and those of its allies. In 2004 CBS and the New Yorker exposed the horrors of Abu Ghraib. In the UK, the Independent’s veteran correspondent Robert Fisk risked his life to report the experience of ordinary Iraqis while UK-based Channel 4 TV asked probing questions about the official version, to the discomfort of the British government.

Many of those who challenged violations of international law and human rights norms in Iraq were all too aware of the evils of the regime which the coalition overthrew. Yet this did not justify the infliction of further abuses on the Iraqis who had suffered so much under Saddam’s rule. There have also been some critics of the West’s action in Iraq, such as the Iranian government, which had dubious human rights records themselves. This does not mean that their criticism was not, on this occasion, justified.

Now, the United Nations has produced a report detailing grave abuses by both the Sri Lankan government and Tigers as the war drew to an end. Much of what is revealed is not new, though some Sri Lankans – both government and Tiger supporters – are in deep denial that ‘their’ side could possibly have done any wrong. (Likewise, there are some Americans, Russians, Congolese, Syrians and citizens of many other nations who strongly resent any criticism of their government’s human rights record, however powerful the evidence of wrongdoing.)

Some people appear to believe that Sri Lanka has been singled out for criticism, and are indignant. Yet the UN, AI and the more enterprising Western news media have exposed human rights abuses by many other national governments, including the USA and European nations, as well as by armed insurgents.

Why make a fuss, others may ask, when such violence is common? Is it not better to accept that abuses occur, and that in the midst of conflict, life is cheap, especially for the poor and powerless across the globe? Yet if violations are not challenged, those waging war are less likely to strive to minimise harm to vulnerable people, and there will be little hope of building a more just and less violent world.

It is also important for victims of violence to have their experience acknowledged, rather than denied. Some measure of justice – at the very least, recognition of their suffering – can help individuals, and communities, to heal.