Colombo, Sri Lanka: 16 December 2010

Dear Sir Arthur,

I write this on your 93rd birth anniversary. Just over a thousand days have passed since you departed.

Like all true rationalists, you didn’t believe in any afterlife. So I don’t expect you to be somewhere there, ‘keeping an eye on us’. You did enough of that during your 90 years on this planet! But as the first decade of the Twenty First Century draws to a close, I find it helpful to address this to you, and to reflect on some of your timeless ideas.

You not only had remarkable powers of prescience and imagination, but also remained upbeat that humanity will survive its turbulent adolescence. As you were fond of saying, you had great faith optimism as a guiding principle, “if only because it offers us the opportunity of creating a self-fulfilling prophecy”.

Three years ago this month, I worked with you in drafting and filming your 90th birthday reflections on YouTube. In just nine minutes, you outlined your vision and aspirations for the key areas of your prolific life: space travel, communication technologies and writing. We had no idea at the time that you had only 100 days left, or that this short video would soon become your public farewell…

Every one of those 900 words is worth another careful read, but I find these to be particularly timely: “Communication technologies are necessary, but not sufficient, for us humans to get along with each other. This is why we still have many disputes and conflicts in the world. Technology tools help us to gather and disseminate information, but we also need qualities like tolerance and compassion to achieve greater understanding between peoples and nations.” (Emphasis mine.)

Easier said than done! Of course, you’d been saying this for several decades about information and communications technologies (ICTs). Few individuals have played a greater role than you in shaping today’s information society. Part of it involved proposing the geosynchronous communications satellite (comsat) and inspiring the world wide web. You also helped build that information society by mentoring technical professionals, advising the United Nations agencies, and gradually preparing humanity to live in an always-connected, transparent world.

For all these reasons, techies worldwide idolised you: some of the planet’s best known geeks were your ardent fans. Among the numerous tributes that poured out after your departure, I found one especially poignant. It was a Joy of Tech cartoon, showing the sentient computer HAL 9000 (from 2001: A Space Odyssey) shedding a single tear in your memory…

In fact, researchers in artificial intelligence (AI) are still trying to create a real-life HAL, which remains the ‘Holy Grail’ in their line of work.

Technology, not politics

Meanwhile, the rest of us are happy (most of the time) with our everyday ICTs. The International Telecommunications Union (ITU), which keeps track of such matters, says the total number of mobile phone subscriptions worldwide will exceed 5 billion by end 2010. There now are 2 billion Internet users in the world, more than half of them in the developing world. Several countries, including Estonia, Finland and Spain, have already declared Internet access as a legal right for all citizens.

For sure, we still have disparities among the connected: for example, between narrowband and broadband, or between 2G and 3G. With so many people getting connected to global telecom networks during the past decade, we are only just beginning to tackle the many legal, social and cultural implications. In finding our way forward in this always-on, multi-channel world, we can do no better than to look up your substantial writing on the subject.

One such profound idea, which many people have been citing in recent weeks, reads: “In the struggle for freedom of information, technology, not politics will be the ultimate decider.”

Wow! In 15 words, you summed up a whole debate that has been raging on for centuries. I recall how you were amused to hear that Rupert Murdoch was fond of quoting these words as he consolidated his ‘Empire of Eyeballs’. You might be intrigued to know that right now, your words are being cited in relation to another Australian: Julian Assange.

The co-founder and editor in chief of WikiLeaks has suddenly become one of the planet’s top newsmakers. He is the public face of this entirely web-based, volunteer driven effort to end secrecy in governments and corporations. Whistle-blowing is as old as the media; what WikiLeaks has done is to provide a digital platform where public-spirited individuals can ‘leak’ secrets safely and anonymously.

We might argue about their modus operandi, but WikiLeaks must be doing a few things right to have rattled many centres of power around the world! The more he is demonised as a criminal or terrorist, the more Assange is attracting the sympathy of millions of ordinary people (not to mention some intellectual and legal heavyweights).

I wonder how you might have reacted to this whole WikiLeaks issue. You cheered every time ICTs enabled the free flow of information and empowered defenders of human rights and democracy, for example, when the Iron Curtain crumbled and the Berlin Wall fell, or when mobile phones rallied around millions of Filipinos for ‘people power’. You were openly gleeful when government censors were undermined first by the comsats and then by the web. (They have since struck back, albeit clumsily.)

Well, you did warn the world’s governments about the coming Age of Transparency. Speaking at the UN headquarters during the World Telecommunications Year 1983, you quoted an unnamed statesman as saying “A free press can give you hell, but it can save your skin”. Our usually reliable friend Google can’t help me on this, but I vaguely remember you saying that it was uttered by Charles De Gaulle.

Your advice at the UN also contained these words: “Exposures of political scandals or political abuses…can be painful but also very valuable. Many a ruler might still be in power today, or even alive, had he known what was really happening in his own country…”

So is Julian Assange simply continuing, in his own style, what people like Sir Tim-Berners Lee (who invented the World Wide Web) and you set in motion in the last century? And isn’t it highly ironic that this latest info-tsunami hits the US government under the watch of a President who himself rode the new media wave to the White House just two years ago?

President Obama must wonder whether the marvels of social media tools are better suited for campaigning than for actual governing. His Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, hasn’t shown much understanding of the new media realities when reacting to WikiLeaks’ dumping thousands of classified diplomatic cables. She apparently doesn’t mean to practise the principles of internet freedom so loftily preached to foreign countries and governments.

Cablegate is only the latest reminder that we are living in a world where few, if any, secrets can be guarded. Governments have long argued they had a right to track and probe the private lives of us citizens, apparently for our own good. Now, a few geeks have turned the tables…

Welcome to the Global Glasshouse!

Surely, there must be at least a few Digital Natives at the State Department to advise their bosses that the Age of Transparency is now unstoppable? And was there no Arthur Clarke fan to remind the mandarins of diplomacy of your time-honoured advice when confronted with new ICTs: ‘Exploit the inevitable’?

Shooting the messenger never worked in the world of old media (even though exposed parties in our part of world keep trying!). With the new media, such action is worse than ineffective — in the WikiLeaks case, it has turned the former computer hacker into an overnight global hero.

These are the times, Sir Arthur, when we want to repeat your celebrated question (asked in relation to the US space program): Is there intelligent life in Washington?

Surviving info deluge

There are many other lessons we can learn from WikiLeaks. For instance: just how can anyone cope with so many secrets disclosed at once?

WikiLeaks is not a bunch of geeks going it alone. Its strength is in working with some reputed media outlets to make sense of the flood of secretive information. Journalists are trained to ‘connect the dots’, and fast. But can anyone process so much new information unleashed by WikiLeaks?

Again, we find you’ve anticipated this many years ago. A thoughtful essay you wrote for Index on Censorship in November 1993 ended with these words: “The real challenge now facing us through the Internet and World Wide Web is not quality but sheer quantity. How will we find anything — and not merely our favourite porn — in the overwhelming cyber-babble of billions of humans and trillions of computers, all chattering simultaneously? I don’t know the answer: and I have a horrible feeling that there may not be one.”

Your caution was made when less than 20 million people worldwide had Internet connectivity. A decade later, on the eve of the first World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) in December 2003, you told me in an interview that ‘humanity will survive the information deluge’. By that time, the world’s online population had grown to 700 million.

You were not only being characteristically optimistic, but reminded us that we’d been at such crossroads before: “There are many who are genuinely alarmed by the immense amount of information available to us through the Internet, television and other media. To them, I can offer little consolation other than to suggest that they put themselves in the place of their ancestors at the time the printing press was invented. ‘My God,’ they cried, ‘now there could be as many as a thousand books. How will we ever read them all?’”

In that interview, you cited discernment as an essential survival skill in the Information Society. Well, the knee-jerk reaction to WikiLeaks has once again shown how that is still in short supply…

Tomorrow’s News?

So if Murdoch was yesterday’s news and Assange is today’s, who might be creating tomorrow’s news — and indeed, shaping tomorrow’s world? This is where we most miss your informed and pragmatic guidance. You used to be our reliable and amiable tour guide to the future.

We can, of course, continue to explore your literary and scientific output in search of possible answers. Two concepts that always interested you were the Global Brain and Global Family.

In your later years, you were intrigued by the phenomenal rise of search engines. As you wrote in 2005: “If comsats are an integral part of the nervous system of humankind, Google must provide part of its brain. Of course, it’s still in early stages of evolution under the watchful eye of its founders. But the future can hold any number of different scenarios.”

Since then, Google co-founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page have continued their quest for online domination. Occasionally, they face spirited challenges from other geeks, notably Apple’s Steve Jobs. You would have applauded Google’s belated decision earlier this year not to put up with mainland China’s internet censorship laws and regulations.

I’m not so sure what you might have made of this thing called Facebook. With more than 500 million active members, the social networking website is the largest of its kind (well ahead of its nearest rival Myspace, owned by your friend Rupert).

Going by the sheer numbers, Facebook is behind only China and India in population terms. But those who compare it to a major league country don’t imagine far enough — it’s really becoming another planet…

While Facebook’s high numbers are impressive, not everyone is convinced of its usefulness and good intentions. Can we trust so much power in the hands of a few very bright (and by now, very rich) twentysomethings? How exactly is Facebook going to safeguard our privacy when we (wittingly or unwittingly) reveal so much of our lives in there?

I raise these concerns not only as a long-time ICT-watcher, but also as the father of a teenager who is an avid Facebooker. I once called Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg a ‘Digital Pied Piper’: might we someday see Hamelin the sequel? (Stop Press: As I was finishing this letter came the news that he is TIME’s Person of the Year 2010.)

But what’s the alternative? Those of us old enough to remember another way of communicating might romanticise about that time past. But do I really want to go back snailmail or fax? Thanks, but no thanks.

It’s not the smart machines and networks we have built, but our intentions and actions that determine what happens next. Again, Sir Arthur, you foresaw us reaching this point and pausing to weigh our options.

You wrote in 1999: “Virtually everything we wish to do in the field of communications is now technologically possible. The only limitations are financial, legal or political. In time, I am sure, most of these will also disappear — leaving us with only limitations imposed by our own morality.”

We need not fear Julian Assange, Mark Zuckerberg or the Google duo — they are merely the ‘midwives’ of the Information Society whose birth cries are now receding into the past. As we discover the enormous powers we have bestowed upon ourselves through ICTs, there is somebody else we need to come to terms with.

It’s the man or woman in the mirror.

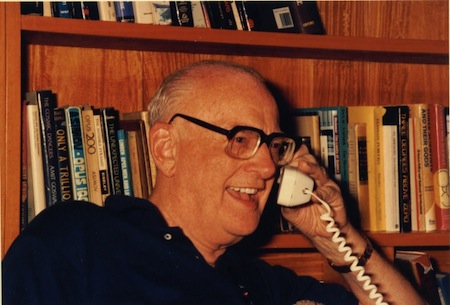

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene worked with Sir Arthur Clarke as a research assistant, and in later years as co-author and media coordinator. He blogs on media, society and development issues at http://movingimages.wordpress.com