On 4th February 2008, as the government celebrated the 60th anniversary of our independence from Britain, it struck me strongly that we Sri Lankans are going round in circles. For some time it has been obvious that ordinary political science terminology and analysis are insufficient and reason inadequate to the strange and twisted trajectory of our country. Sights and insights that stimulate deeper thought on these points are captured in Stephen Champion’s book of photographs, Lanka War Stories, the best account I know of the recent history of our tortured nation. This small essay cannot be an ordinary review because these are images of my own experiences; they trace the life of my generation. I remain inside the book, not a commentator but a participant.

In the late ‘80s, when I was studying GCL courses in southern Sri Lanka, we were in the midst of two civil wars. In the North the minority Tamils were fighting to liberate themselves from the oppressions of the majority Sinhala state. In the South, the exploited under castes and classes sought to be free from the social injustices of that majority society by taking power themselves.

We have a tradition, I believe from the Portuguese, of reciting poems for seven nights of mourning after a person has died. During my teenage years the poems we heard every day were the screams of the bereaved, amidst the smell of bodies burning in the streets or lying on pathways at the edge of fields or forests. This situation transformed us; we had to learn to survive. So we walked past the dead bodies concentrating hard on our studies, avoiding the sights, trying not to know what was going on around us.

A small magazine of the time, Ravaya (Voice), carried a photograph of a little boy leaning against the post of a roadside fence, his head bowed. In front of him lie two mutilated bodies, awkwardly strewn, burned, chopped and distorted. Suddenly, I was the boy standing there, unable to look at what I had already seen. From this moment I could no longer ignore the horrors going on around me. There was no indication of where the photograph had been taken or by whom. For ten years I tried to find out who it was.

(c) Stephen Champion, All rights reserved

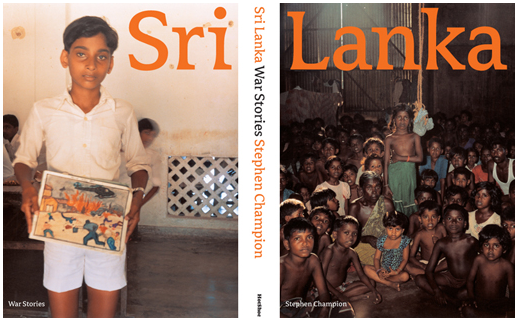

Although the photographer did not know it, this image (reproduced here on page 121) became iconic. It has been reappearing for twenty years; used – abused – by different political parties whose campaign posters promise: if you vote for us this will never happen again. Eventually I discovered that the picture had been taken by Stephen Champion; a person who has been photographing Sri Lanka for more than half my lifetime, a person who was important to me long before I knew him. His work is important to all of us who have survived – when so many thousands have not – because he has documented what our generation has been living through, the worst years ever in our country’s history.

Outsiders have been mapping, drawing, documenting and photographing Sri Lanka from the times of Ptolemy, Huin San, Fhahian and Iban Battuta, through the European colonisations by Portuguese, Dutch and British, until the present day. Sri Lanka is an exotic and beautiful island, colourful, drenched in strong tropical light during the day and pastels at dusk. A seductive paradise for the early travellers and for the tourists of today; this exquisite setting is also ravaged by tragedy, as bitter in its pain as it is beautiful in the blessings of nature.

Stephen is one of four leading contemporary photographers of Sri Lanka – the others being Nihal Fernando, Dexter Cruse and Dominic Sansoni – whose work most effectively conveys the beauty of our island and the events of our times. Dominic Sansoni’s skill is in his eye for the colours of Sri Lankan life; whether taking beautiful or tragic images, his concern is always with the colours. Dexter Cruse’s great ability is in capturing incidents, significant moments; and Nihal Fernando is the master photographer of Sri Lanka’s exquisite beauty.

Stephen Champion’s work is totally different from these. Although a photograph can only capture a single moment in the flux and process of life, for me Stephen Champion’s images do more than this. The moment is there, but so too is its context, caught not only in the perceived space but also in time; so that each image is emblematic of matters larger and deeper. A prism, the image conveys not just one but several planes of meaning, experience, emotion, reality. The drama of the picture is more than its beauty or its incident; it is the drama of something incomplete that emerges from a specific past and continues into its future. These dimensions of time are outside the moment of the picture but resonant and incandescent in its telling instant. Stephen’s images are often angry and outraged; they are also sarcastic, satirical and ironic. They make an argument, state a view, evoke a discourse; they challenge and insist upon engagement and response. This is not an easy encounter.

The design of the book immerses us in the Sri Lankan situation; this is not just about the Sri Lankan war, it is about Sri Lankan life. Stephen’s lens finds monks meditating in their hermitages, official, rebel and paramilitary killings, displaced people, soldiers, police, mothers, widows, teenage lovers, teenage fighters, bordellos, hospitals, rice paddies, environmental pollution and many other juxtapositions of militarism and ordinary life, of normality and the abnormal, of the brooding paralysis of permanent trauma.

Most of these images are arranged in pairs that show how beautiful the country is and how brutal, how innocent and how violent, how mellow and how melancholy. The landscape, the seascape, the living and the dead are juxtaposed with a poignancy that reveals dimensions deeper than their contradictions. Even the orange chosen for the endpapers and the title is semiologically resonant, because for Buddhists this colour symbolises the essential and eternal truths of their religion – wisdom, strength and dignity. Subtly, obliquely, these pictures show how inadequately such Third World realities are conveyed or understood using conventional political or sociological analysis. The complexity of this terrible, unmagical realism can only be sensed through nonverbal means.

Let me mention a few more individual photographs. On page 30, a dead body lies on the ground covered by a sarong. Across the middle of the picture is a woven palm leaf fence. On the other side of the fence kids play, jumping and frolicking, watched by other children and smiling adults. They do know the body is there, it is easy to see; but the corpse is not one of theirs, so they are not concerned. This is daily life.

On page 39, we see “School children on parade, Independence Day, Colombo”. Along the Galle Face, as far as the eye can see, children are marching towards us on the beach. From an army jeep in the foreground, soldiers watch the schoolgirls in white dresses, white socks and white shoes, with their long black plaits, swinging their arms in military unison.

(c) Stephen Champion, All rights reserved

To satisfy the international community countries must have elections to demonstrate their democratic credentials. On pages 130 and 131 of Lanka War Stories there are two photographs of Sinhala graffiti from the time of an election in the late ‘80s. The one on the left reads, “If you vote in the election you will be killed”. The one on the right, “If you do not vote in the election you will be killed”.

(c) Stephen Champion, All rights reserved

We are trapped inside such moments, our daily sights and sorrows. They drain us of wisdom, strength and dignity until consciousness becomes a vacuum. Stephen’s photographs record how stark and total our losses have been and continue to be. They also show the forces responsible. Sinhala and Tamil nationalism, Buddhist fundamentalism, political mismanagement, caste, class, gender and ethnic hostilities, failures of the left, arrogant and corrupt aristocracies, propaganda fantasies that idealise futures which can never be – all these have left us ungrounded, focused on dreams, mirages and hopes whilst we descend ever deeper into our vortex of catastrophes.

Stephen Champion has produced two books in the past twenty-two years: Lanka 1986-1992 and Lanka War Stories. His images make it clear that we are going in circles. The past reproduces its patterns in the present and cycles its way into the future; a past whose tragedies our elders have unwillingly bequeathed to us, as we shall unwillingly bequeath them to the next generation. But are these photographs more than mirrors and memorials? Could they be windows that can open us to a better understanding of ourselves?