Featured image courtesy the Quint

Editor’s Note: This article first appeared in “Exploring Confrontation: Sri Lanka- Politics, Culture and History” and is not easily available online. It is published here, with permission, to mark 35 years since Black July.

Two Survivors

Not all Tamils in Sri Lanka are Tamils. A few who have been born and bred in the South-Western parts of the island have been de-Tamilicised. They know very little spoken or written Tamil. They speak (as distinct from read) colloquial Sinhala with some level of fluency and without those inflections which indicate to all and sundry that one is Tamil. In the heat of ethnic conflict such a capacity is critical. Language in its phonetic, oral form becomes a matter of life and death – a technique by which assailants identify whom to hit or kill, a line which differentiates those who stay alive with those who die.

Two friends of mine, de-Tamilicised Tamils, stayed alive that fateful week in July 1983. One is an old schoolmate born and bred in Galle, my age now, circa 53 years. I shall call him Damian. He is in a professional job of the stratum: lawyer, doctor, accountant, engineer. Unlike others of this stratum, he has never left Sri Lanka and has no desire to do so, even though several siblings live abroad. Damian’s wife is not Tamil. Like Damian, she is a Catholic. Their house is in Colombo, off a main thoroughfare, Galle Road, perhaps by 80 yards. Though de-Tamilicised, his patrilineal name is manifestly Tamil. Several of the gangs that roamed the streets of Colombo during the pogrom of 1983, as we all know, had electoral lists which identified Tamil properties and/or householders. Whatever Damian’s self-perception of his ethnic identity, his name made him a target.

Most Tamils who were targets of this sort moved into safe houses, that is, where they were not caught unawares during the initial round of attacks. Damian did not. When mobs were roaming about Galle Road in the vicinity of his house, he simply joined their fringes as a bystander. He could pass. He is alive today and laughingly ‘dismisses’ the experience.

So, too, is my friend Veegee alive today. But he had a close-call. Veegee is born and bred in Kandy. We became good friends at Peradeniya University. We have not met for many moons. Veegee is married to a foreigner and has been teaching abroad for several decades. Veegee chose to visit Sri Lanka, after a long lapse, in mid-1983. When the pogrom broke out, he moved into the house of a Sinhala friend.

As the situation quietened, he was picked up by another friend, TW, a Sinhala lawyer. TW and Veegee were driving in the vicinity of Kirulapona and the Colombo South Hospital when they were warned of renewed violence ahead. TW took a detour, only to find that they had driven into a hornet’s nest of burning, demolition and killing. TW parked the car in a suburban side-street and went by foot to secure help.

Veegee, now alone beside the car, prepared the ground for his survival by talking to the neighbouring householders in his rusty Sinhalese and emphasizing the fact of his long residence abroad. A gang of assailants, armed with axes, katties and rods, accosted him. Most of them wore sarongs rather than trousers or shorts. They ranged in age from youths to men in their 40s or 50s – if one were to judge age from appearance. They were ‘ordinary fellows’. They were not seething with rage or glee. There was a cool matter-of-factness, tinged with an aura of bravado following good work well-done, in their method of discourse. This discourse now had Veegee in sharp focus.

Their spokesman wanted to know his name. Using the first two syllables of his Tamil name, he gave a Sinhala name of the same beginning (how the patrilineal histories of the two people intertwine!) “What is your ge name?” they demanded. “Lokuge,” he lied. “What is your village?” (that is, where were you born). “Welikade,” said Veegee. This was calculated testing before the possible kill.

They were only partly satisfied. They moved away pondering. Someone had seen TW disappearing in the distance and linked him to Veegee. TW was portly and dark. As a stereotype, Tamils are dark – kalu. Some of the gang came back to Veegee. They referred to TW as ‘eh maha kalu tadi demala’ (that large, black, huge Tamil) and wanted to know his name. Veegee gave TW’s real name, a name known to some of the gang. They showed disbelief. And continued to ponder over Veegee’s identity – not being entirely dissuaded by a neighbouring Sinhala householder’s (this man was a Government official) insistence that Veegee was a Sinhalese.

They told Veegee they had killed a few Tamils a few streets away. They displayed the blood on one axe. “Would he come with them and look at the bodies?” This, says Veegee, in retrospect, was a ‘litmus test.’ A good Sinhalese was expected to join in this grisly review. Veegee, continuing to struggle in his rusty and incoherent Sinhala, indicated that he was allergic to blood. The suspicions of the gang moved up several notches.

The assailants then decided to burn TW’s car, some yards away.

As they prepared to do so, Veegee ran forward and insisted that TW was Sinhalese. ln scolding style he asked them to consider the enormity of their intention: burning the car of a Sinhalese! Veegee then opened the door, found TW‘s briefcase and rummaged among its papers. He discovered, and showed, a document with TW’s name on it. The gang was not entirely convinced, but was now more doubtful. One assailant reasoned aloud: if this fellow was Tamil he would not have run back to the car.

At this point TW turned up in a police jeep. The gang did not run away. They outnumbered the policemen. The policemen treated Veegee as if he were a Sinhalese (though they knew he was not). TW’s credentials as a Sinhala were manifest in his speech and demeanor. Veegee was whisked away in the jeep, while TW drove his car to the police station behind them.

It was a close call for Veegee, a chilling moment with many chilling moments. He had matched the bravado of the assailants with his own bravado, an instinct for survival. Demeanor had been a discourse for survival. This, clearly, secured his life. But it had been touch and go.

For young Arumanaiyagam, this was not to be.

One killing, One friend no more

Arumanaiyagam was a Jaffna Tamil. With me he was perhaps more acquaintance than friend; he was in the nebulous border zone of acquaintance/friend. Of a cohort that graduated when I was teaching Sinhala at Peradeniya. I got to know him as a younger colleague teaching in the Tamil stream at the History Department, University of Peradeniya.

His was a temporary appointment, however, and he joined the Income

Tax Department as a government executive in the 1970s. As such he lived and worked in Colombo. I had never spoken with him in Sinhala, but one can safely assume that his Sinhala speech was heavily inflected with Tamil diacritica. During a pogrom, diacritica is stigmata.

When the pogrom began, I gather that Arumanaiyagam and his family moved to safe houses and eventually into one of the hastily established refugee camps in the heart of Colombo. As quiet returned, uneasily, Arumanaiyagam and a Tamil friend felt sufficiently secure to venture forth in one of their cars in order to enjoy a sea-bath. An ‘everyday’ act during a not-so-norrnal occasion. And then the not-so-normal became quite abnormal. This was the morning of the panic, the 29th July 1983.

And as the panic spread. so did the killings begin anew. The day of the panic was also the day of renewed mobs. And more killings.

Arumanaiyagam and his friend were accosted by a gang as they drove back. They may have been burnt alive in their car.

The story of his death was related to me by another history graduate of his day, a Sinhalese whom I meet often in the course or my work. I have not attempted to verify the story because l have no reason to doubt it; and I have long ceased to be amazed at the degree of precise detail which oral accounts embrace in their recounting.

When I heard this tale, seated in an ordinary chair in an ordinary office, my response was not dramatic and matched the matter-of-fact narrative. I did not exclaim. I did not hold my head in my hands. That‘s perhaps my way. But I remembered. I have not forgotten. This is my epitaph to Arumanaiyagam.

Agony -and Defiance within Agony

Prose fails, often, at such moments. And where prose falters, poetry recovers the moment. A Sinhala lawyer, Christian by background, Basil Fernando has attempted to capture facets of the July pogrom in poetry.

His “Just Society” is a stinging indictment of the burners and killers, and of Sri Lankan society, his society, my society. It has its sequel in another poem, another indictment; which he called “Yet Another Incident in July 1983.”

The irony in the phrase “yet another” is powerful in its effect and is surely intended. But one could think of another title: “Defiance within the Agony. ” For within Basil Fernando’s poetic account of a happening that week is an evocation of Arumanaiyagam’s agony. And the pain and agony of all the Tamils killed that week. And yet more: within Basil Fernando’s indictment lies the indelible defiance expressed by a resolute Tamil person about to suffer a horrible fate. To verse, to verse:

Burying the dead

being an art well developed in our times

(our psycho-analysts have helped us much

to keep balanced minds-whatever

that may mean-) there is no reason really

for this matter to remain so vivid

as if some rare occurrence. I assure you

I am not sentimental, never having

had a ‘break down’ as they say.

I am as shy of my emotions

as you are. And I attend to my daily

tasks in a very matter of fact way.

Being prudent too, when a government says “Forget”

I act accordingly. My ability to forget

has never been doubted, never

having had any adverse comments.

On that score either. Yet l remember the way they stopped that

car,

the mob. There were four

in that car. a girl, a boy

(between four and five it seemed) and their

parents-I guessed-the man and the woman.

It was in the same way they stopped other cars.

I did not notice any marked

Difference. A few questions

in gay mood, not to make a mistake

I suppose, then they proceeded to

action, by then routine. Pouring

petrol and all that stuff.

Then someone noticed something odd

as it were, opened the two left side

doors, took away the two children, crying and

resisting as they were moved away from their parents.

Children’s emotions have sometimes

to be ignored for their own good, the guy must have

thought. Someone practical

was quick, lighting a match

efficiently. An instant

fire followed, adding one more

to many around. Around

the fire they chattered

of some new adventure. A few

scattered. What the two inside

felt or thought was no matter.

Peace loving people were hurrying

towards homes as in a procession

Then suddenly the man inside

breaking open the door, was

out, his shirt already on

fire and hair too. Then bending,

took his two children. Not even

looking around as if executing a calculated

decision, he resolutely

re-entered the car.

Once inside, he closed the door

himself. . . I heard the noise

distinctly.

Still the ruined car

is there, by the road-side

with other such things. Maybe

the Municipality will remove it

one of these days to the Capital’s

garbage pit. The cleanliness of the Capital

receives Authority’s top priority.

When I first read Basil Fernando’s poem, around 1985, it reached through to the bone in the raw. l did not think, then, that the chilling details within the poem were a case of poetic imagination (justifiable though such license would be). It was too authentic in its detail to be anything but a scene witnessed. Safely witnessed as a Sinhalese. A pained Sinhalese.

This supposition has since been confirmed. It was not something witnessed by Basil Fernando, but an incident witnessed by one of his Sinhala lawyer friends -at Narahenpita close to the “labor secretariat.”

Having seen some of the mayhem himself, to Fernando the story was part of “the general pattern of violence those days” -what Fernando sees bitterly as “the routine,” with the parentheses being his emphasis.

l have been an eye witness to that routine many times, and l have seen how the police looked the other side It was usual in the dates that followed the July violence to talk details about the incidents all the time. This was told in the course of such a conversation, when there were several others. No one was surprised by the story, says Fernando.

In his circle of friends there was an “angry and sad mood” about the happenings of the pogrom and Fernando’s poems are explicitly intended as “a critique of the middle-class” as well as being an attempt to grapple with his internal turmoil at having outwardly accepted the course of events.

My interest, here, on the other hand, is in the lucid indictment expressed by that unknown Tamil father. To me, at first reading, then, now ever more, always, the action pressed so resolutely by that unknown Tamil man, a Tamil father, spoke more eloquently than words. His was the most profound of statements. It was an act of rebellion. It was an act of condemnation. A double gesture, an indictment of humanity in general and the Sinhalese in particular. Its courage, its resoluteness, its incisive clarity of comment has etched its imprint on my soul.

Others may draw different meanings. Or like ones. Every text is amenable to several meanings, and thus to several audiences. I could translate what I think that unknown Tamil victim was saying into earthy Australian slang. But such words would offend, not only because of their earthiness, but because everyday slang, being so common (in both its senses), would traduce the profundity of that Tamilian’s ‘words.’

Ecstasy

Survivors, victims, those grieving the bereaved, those grieving the loss of their worldly possessions, these are, as one knows, the flotsam and jetsam of war and pogrom. Yet, intimately entwined within these moments are those who perpetrate these fates.

In any pogrom there are inciters and stirrers, killers and maimers, arsonists and Iooters. These individuals are not merely “rabble,” “miscreants,” “savages,” “drunken criminals,” and “paranoids.” They are not just “bloodthirsty hoodlums” though some criminal hoodlums would indeed be involved. Such epithets are part of the lexicon by which the intelligentsia and the middle-class distance themselves from the hellfire of a pogrom. It is, l reiterate, a casting of responsibility unto those beyond the margins of normality. Yet, to repeat, pogroms are a potential within normality, a capacity within the human, “peace and politics by other means.”

The fierce actions of assailants during a pogrom, in my surmise, could be as agents of state doing a job. They could be cool, calculated Machiavellian operations. Or they could be acts of rage, in a frenzy perhaps even a frenzy that had been crystallized through a transitional moment of chilled horror as a group of tense people digested an atrocity story circulating like a wildfire. “Frenzy” is the typical mint coined by the intelligentsia and the respectable bourgeoisie to depict the assailant whenever they review an ethnic riot or a pogrom.

This, as we have seen, is not false coin. Alongside the sort of cool bravado displayed by those who interrogated Veegee, anger and rage, retributory acts of vengeful killing and arson, are there aplenty in the twentieth century pogroms and riots of Sri Lanka. But rage is not the only form of embodied emotion in the moment of the striking. Euphoria, ecstasy and glee also prevail.

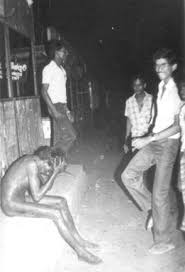

A local photographer happened to capture just such a moment in July 1983. His photograph depicted a few youths, one men of them poised to kick a young victim, deemed Tamil, stripped naked, laid bare, forlorn and terrified. This was, I have little doubt, a few moments before he was killed. This occurred in the suburb of Borella, near the main bus stand, at 1.30 am, on the 24th July 1983, Black Monday as it is sometimes referred. It would have been among the earliest killings during the pogrom.

Gleeful kick: scene at Borella Junction on the night of 24-25 July 1983. Picture by Chandragupta Amarasinghe, then attached to the Arts newspaper. My original speculation in Exploring Confrontation that the terrified Tamil man was killed has been confirmed by Amarasinghe. The principal assistant has been captured on camera as he swiveled around to deliver a karate kick. During an extended tapes interview Amarasinghe confirmed the fact that the assailants enjoyed their work.

The work of retributory vengeance, was gleeful work. Joy is writ clear on the bodies and faces of those involved. It is almost as if such a moment was akin to the moment of victory after a game of buhukeliya (A children’s game usually (in the past) popular during the time of the Sinhala New Year) or a rite of ankeliya (pulling the antler’s horns, a ritual game to ward off evil from the community involved in the rite). The practices of ritualized humiliation heaped on the losing sides after these contests have been described by observers over the centuries as shameless, beastlike or vindictive, and marked by “unbounded license” and “filthy obscenity.”

Bystanders after the burning and assaulting: also at Borella Junction area, 24-25th July 1983, picture by Chandragupta Amarasinghe. There is a suggestion here that popular participation in attacks were also initiated and/or facilitated by state functionaries. It is also likely that some of those described as ‘bystanders’ were perpetrators of some of the destruction, burning and killing. I had not discovered whom the photographer was when Exploring Confrontation went to press. Let me use this occasion to record my greatest respect for the bravery and ingenuity revealed by Chandragupta Amarasinghe in extremely dangerous and trying circumstances.

Ecstasy II

Such exhilaration during a pogrom, in my further surmise, was not entirely idiosyncratic. A Sinhala friend of mine related another tale which suggests this extension. He happens to live in Kandy, in a ‘respectable’ street off Peradeniya road. ln the locality of Kandy, too, the pogrom of July 1983 was quite widespread and quite severe. At the height of the troubles, a gang of youths entered this street looking for specific Tamil houses. One of these was occupied by an old Tamil lady. She was not there, having gone into hiding beforehand in the house of a Sinhala neighbor. So these youths set to work smashing up the house, while bystanders, my friend among them, watched. The assailants found the owner’s Alsatian in the course of their ‘work’. The dog was cut to pieces.

They enjoyed all this. It was high-fun.

Ambiguity

One sunny day in 1991 I gave an old Muslim (Moor) gentleman a lift from Kandy to Matale. I shall give him the pseudonym, Mr. Kiwi, with the Mr. signaling my hierarchical respect for his age and sagacity. Mr. Kiwi, I discovered, had a shop in Matale town. So, as we motored along, I casually inquired after the happenings in Matale in July 1983. Some

Sinhalese, he said, had smashed up the Tamil shops in the bazaar. He had come out and watched. And as he reached the nearest junction, he heard a few of the Sinhala youth, who were gleefully wrecking havoc, shouting jatika sevaya, “in the service of the nation” (or “national welfare” if one wishes to be literal).

This account loses something in the telling, a loss that is compounded by my failure to probe further -through critical questions seeking greater precision in meaning. Thus hamstrung, we do not know whether there was an ironic twist of phonetic inflection attached to these shouts. Were the youths amused that there would be a nationalist goal in the sort of destructive work they were carrying out? Was there, then, a cynical sagacity in their comprehension of the pogrom? Or, was theirs a serious claim? Was there a nationalist fervor, the zealousness of bigotry, underpinning their happy work?

I cannot be sure.

Editor’s Note: To view more content marking 35 years since Black July, click here.