Featured image by Raisa Wickrematunge

On July 2, 2018, Hiru TV aired footage from two press conferences hosted by the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) during its 6:55 pm broadcast.

During the press conference, the members of the Joint Opposition reacted to a story run by the New York Times, which focused on the deal around the Hambantota Port to illustrate the argument that China’s Belt and Road initiative was exploitative and left countries like Sri Lanka struggling with debt. (The Belt and Road initiative involves China underwriting infrastructure investment such as roads, ports and airports for countries lining the old Silk Road route.) It is an argument that has been gaining some traction, particularly after reports noting that Zambia, the Republic of Congo have had to turn to the IMF for assistance after taking on Chinese loans. T

The former Governor of the Central Bank, Nivard Cabraal was the first to respond to the story, releasing the full audio clip of the interview in which many of the question asked by the New York Times remained unanswered. The former President also released an official response.

On Twitter, a number of newly created accounts began trolling those who posted about the New York Times story. This account, for instance, had one post on strawberry tarts, and then tweeted almost exclusively about the New York Times.

From strawberry tarts to the #Hambantota port – this account which has 0 followers, and has been inactive since 2017 is very interested in Sri Lankan politics and the recent @nytimes story on China in particular @Abihabib #lka #SriLanka pic.twitter.com/iZpJHuF2FK

— Groundviews (@groundviews) July 2, 2018

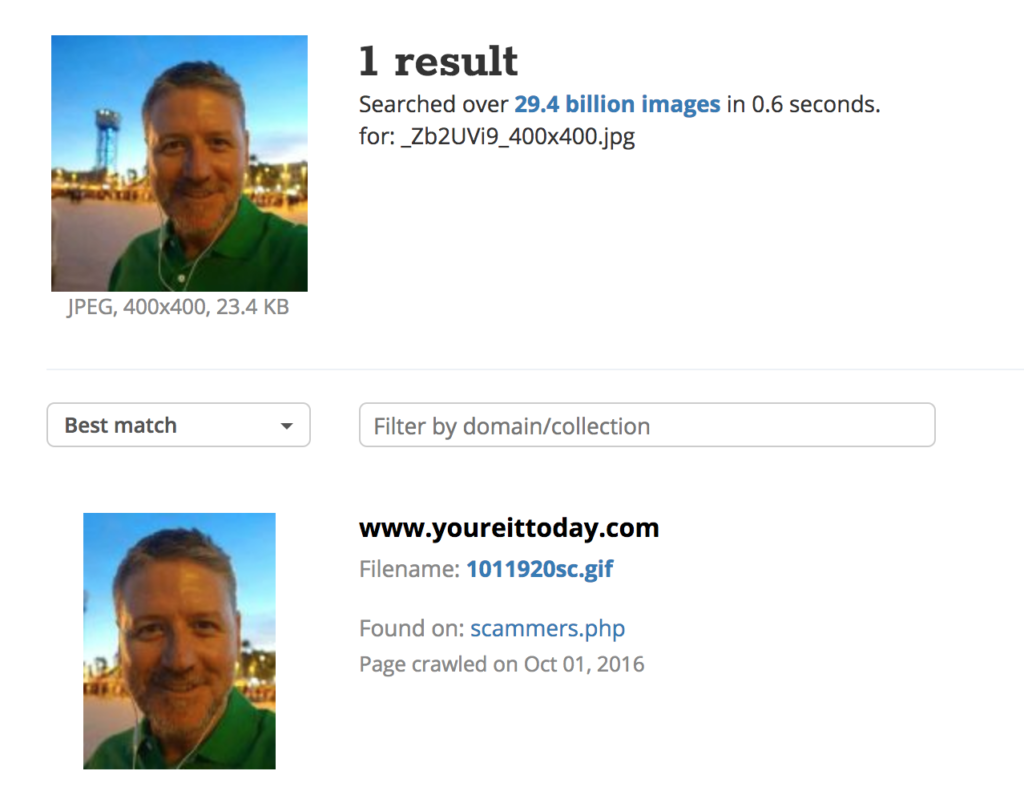

This account’s tweets were ‘liked’ by many members from the Rajapaksa camp themselves, including by Namal Rajapaksa. While this is unsurprising, given the slant of the tweets, it does not bode well that running a reverse image search on the profile photo revealed that it had previously turned up on a (somewhat garish) website meant to showcase photos of people which had been hijacked by scammers.

But this was far from the end of the saga.

This clip, broadcast on @hirunews 6:55 pm telecast on July 2, 2018, shows MPs speaking about the Sri Lankan journalists who provided logistical assistance on the @nytimes story on #Hambantota Port. Excerpts to follow https://t.co/X4guTMwis8 #lka #SriLanka #FoE #mediafreedom

— Groundviews (@groundviews) July 3, 2018

Provincial Council member of the Southern Province and MP Kanchana Wijesekera named two Sri Lankan journalists who had provided logistical assistance on the story and noted that they were both close allies of Minister of Finance and Mass Media, Mangala Samaraweera. At the SLPP headquarters in Colombo, G L Peiris said that they were “hoping to take it to American courts, but we will start with a case in Sri Lanka.”

Over the next week, the former President, his son and other allies said the Rajapakses were discussing legal action against the New York Times.

Then, in a swift (and perhaps predictable) about-turn, Rajapaksa said he was planning action against a local newspaper instead.

.@PresRajapaksa, @RajapaksaNamal and @SenaniSL all said former President would file legal action with @nytimes shortly (see https://t.co/jp1BuhlCBt https://t.co/sVQWotGXGb and https://t.co/8rDkXSleX0). Now says the opposite. What changed? #lka #SriLanka pic.twitter.com/KpiR5HWWCh

— Groundviews (@groundviews) July 5, 2018

It must be noted that the Government itself has often fallen short of its stated goal of preserving media freedom.

In a separate incident earlier this week, Coordinating Secretary to Mangala Samaraweera Thusitha Halloluwa lambasted a journalist who was calling him to follow up on a story on corruption, issuing verbal threats.

Since 2015, there have been 14 websites blocked in Sri Lanka. The most recent of them, Lanka E News, was blocked on order from the President’s Office.

The site remains blocked, to date.

In 2016, the Government renewed orders that news websites register with the Ministry of Mass Media, which would involve revealing details of ownership and addresses of media institutions.

During riots targeting the Muslim community in Ampara and Digana and its surrounding environs in March, this Government maintained that the blocking of social media had somehow helped to stem hate speech, even when it demonstratively had not. President Sirisena went so far as to say the income of Sri Lanka Telecom and the TRC had increased after the block, and both he and the Prime Minister spoke about introducing regulation on social media, even though there are existing regulations that could be implemented to curtail hate speech.

If these events illustrate one thing, it is that, across political divides, freedom of expression is often not a priority, mentioned as a punchline only when politically expedient.

Yet the words of the Joint Opposition at the press conference on July 2 cannot be dismissed as mere political rhetoric. They were publicly delivered, personal in nature and clearly intended to undermine both journalists’ credibility and frighten them into silence. The effects of this may extend into the future as well, for journalists working with foreign correspondents in any capacity.

This is not the real crux of the story.

While the journalists reporting the story are being publicly held to account, there is no such move to hold the former Government to account for the allegations made in the original article. After Deputy Minister Ranjan Ramanayake filed a report with the FCID, a cheque circulated showing that a deposit had been made by Colombo International Container Terminals to a fund run by the wife of ex-Minister Basil Rajapaksa. This transaction was already made public knowledge in 2015, with details handed over to the Financial Fraud Investigations Unit. Allegations that bribes were paid by Chinese firms to the Rajapaksa’s campaign fund surfaced in 2015 as well. There is no public record of the outcome of these investigations – and the fact that a fresh inquiry appears to have begun only after Ramanayake’s complaint does not indicate that there was much progress.

It is clear that the Joint Opposition very much wants to obfuscate and divert public attention from the allegations made with regards to Chinese funding, by the New York Times and others.

The question is why this Government remains so reluctant to hold them to account.

Editor’s Note: Also read “Corruption and Complicity: Perceptions from Across Sri Lanka” and “Conviviality and Censorship: On Media Freedom in Sri Lanka“.