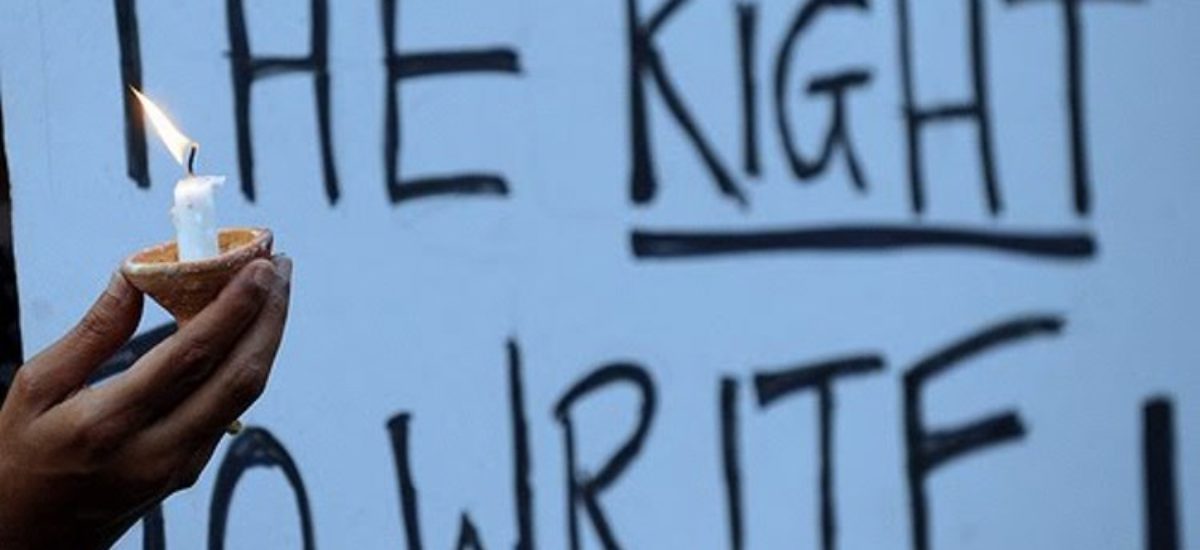

Featured image courtesy Sri Lanka Brief

Sri Lanka ranks 131 on the Reporters Without Borders 2018 World Press Freedom Index, an improvement of 10 points in the space of a year. The reason for this may be the line of red zeros within the country report – no journalists, citizen journalists or media assistants were killed in Sri Lanka 2018. However, as the Index notes, many of the investigations into killings in the past have gone unpunished. The world has already begun to forget. In 2016, Sri Lanka dropped off the Committee to Protect Journalist’s Impunity Index for the first time.

Yet, answers for past killings and abductions have not been forthcoming. April 28, 2018 marks 13 years since Dharmaretnam (alias “Taraki”) Sivaram was abducted. Journalists in the North and East staged protests, highlighting the continued call for answers in his case. From 2017 to 2018, there have been continued restrictions on freedom of expression in areas like Mannar and Mullaitivu where journalists and activists have been detained or assaulted over the past year.

journalists from north and east staged a demonstration today in batticaloa calling for justice for murdered Tamil journalist Dharmeratnam Sivaram and 43 author journalist pic.twitter.com/Kcaoj0pYYP

— sabeshwaran (@sabeshwaran) April 28, 2018

A point often made when speaking of press freedom in Sri Lanka is the progress made in the case of Lasantha Wickrematunge. This year, there has also been significant progress in the case of Keith Noyahr, with direct links made to former military intelligence and to Defense Secretary Gotabhaya Rajapakse. These markers of progress are indeed encouraging. Yet this erases the long wait families of journalists like Sivaram, Prageeth Eknaligoda, Mylvaganam Nimalarajan and others.

On January 8 this year, I delivered this speech to mark 9 years since my Uncle was shot while driving to work. In light of World Press Freedom Day, I believe it is important to share, to highlight continued challenges Sri Lanka faces in this arena, and also to note the fallacy of flagging progress in symbolic cases, when so many others remain unresolved and unexamined.

“When I think of my uncle, or Baappi as my sister and I called him, my first image is of him pirouetting and saying “I’m a ballerina!” This was in response to me asking him why he had such a special affinity for pink, because the last three times I had seen him, he was wearing a pale pink shirt. To me, that memory best sums up Baappi’s spirit – irrepressible, charming, mischievous.

There are other images too. Images of him asking “What’s for dinner?” while poking his fingers into saucepans in our kitchen, of prank calls (especially on April the 1st, which I think was his favourite holiday). Or of him telling someone, for the hundredth time, that it would be a disaster if I married someone whose last name was Soysa, because I’d become Raisa Soysa, a joke which he cracked ever since he first heard about my parents choice of name, and which never failed to annoy me.

Memories of him seriously telling me that my biggest test in the newsroom would be making the perfect cup of tea. I have to add that the reason I was in the newsroom at all was largely thanks to him, and his encouragement. Whenever he came to our house, he took the time to talk to the shy, awkward child sitting in her room with her nose in a book. I never thought he noticed me any further than that – so I was surprised when he coaxed my parents to allow me to join the Sunday Leader. In doing so, he gave me a gift I can never hope to repay. Not just the ability to express myself, but also the ability to widen my own world-view by opening my eyes to the many stories of poverty and injustice that surrounded me, and to which I would otherwise have remained oblivious.

I find it difficult to talk about these memories. Over the years, I have come to feel like those memories are treasured possessions. I worry that as time passes I might somehow lose the memory of his laugh, or the way it felt when he ruffled my hair. This is partly why it has been so difficult for me to speak at these services. It is a strange thing to find yourself being asked to examine your private memories and speak them aloud in this way.

But I am not unaware that at least, people are listening. My Uncle happened to be killed in broad daylight, in Colombo, near an Air Force checkpoint and next to a high security zone. The way he was killed was clearly premeditated. When they speak about Baappi’s case, they call it “emblematic”. A symbol. I discovered just how symbolic when I was covering the International Day to end Crimes of Impunity Against Journalists two years ago. As part of the piece I did for Groundviews, I spoke to Sandya Eknaligoda and the editor of the Sunday Thinnakural, Bharathi Rajanayagam. On both occasions, it gave me a jolt to see photos of my uncle; pinned to the noticeboard in the Sunday Thinnakural, and on a wall in Sandya’s home. Both of them spoke about Baappi’s case but also about the many others that have remained unresolved, to date.

According to CPJ, there are 19 journalists whose killings were due to the work they carried out, and under very trying circumstances.

The Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka have different figures, counting over 40 journalists and media workers killed, abducted or tortured while carrying out their work.

Each of those journalists had a family. Each of them have treasured memories of their loved ones, as I do. And they have the added pain that, apart from the one day a year that marked their death or disappearance, and some sporadic coverage on those days, their names and their work has been forgotten. So much so that, to my great shame when I visited the Sunday Thinnakural office, there were names and stories that I did not recognise.

Subramaniyam Sugitharajah, January 2006, Sudar Oli. Subash Chandraboas, April 2007. Mylvaganam Nimalarajan, October 2000. These names, and others don’t receive the same attention or coverage as my uncle’s case. Why have we forgotten them?

I realise that what I say has political implications. I have always shied away from the idea that the uncle I so loved should symbolise anything other than himself. This, too, has been the main reason why I did not speak out until now.

And yet the large crowds at his funeral, the rally outside on that day, the photos of my uncle pinned on the walls of the Sunday Thinnakural, and the people who attend this service speak otherwise.

I believe that, if Baappi were alive, he would not want us to forget those names. I believe that his voice would join mine, if he were still here. But he paid a price for his outspokenness. And so did all the others. I think that is important to remember on this day. Today marks nine years since Baappi decided to drive to work, even though there were men on motorbikes following him. In 2016, CPJ dropped Sri Lanka from its Impunity Index – largely due to the passage of time.

While the rest of the world moves on, we as family members continue to keep time. Certain days for me, will always have a painful significance. April Fool’s Day, the day when Baappi would prank call my mother, April 5, his birthday. And now, January 8. Over nine years, there has been little in terms of tangible progress in bringing the perpetrators of his murder to account. And we are the lucky ones – interest and investigations into so many of the other cases are not sustained.

I could end on that note, and say that things feel hopeless. But I think Baappi would not want me to give up so easily. I think he would not have given up so easily, either.

So instead, I am going to end with one plea. I would ask everyone gathered here, many of whom are here either because you knew and loved my Uncle, or were inspired by him, to raise your voices against the injustice you encounter. I ask that, in whatever way you can, you ask difficult questions about what is right and wrong, not just of others, but also of yourself. And I ask that you work towards righting the wrongs you encounter, in whatever way you can. Let us all work towards a society where critique is responded to with informed debate, not with senseless violence. Let us work towards a society in which all forms of violence are not tolerated or worse, hidden away, because they are inconvenient to examine.

I believe that would be a beautiful way to preserve the memory of my Uncle, who fought passionately for what he believed in.”

Editor’s Note: Also read “Freedom of Expression on the decline in Sri Lanka“