In light of a recent spike in suspicious activity on Twitter in Sri Lanka, Groundviews is pleased to publish a detailed report co-authored by Senior Researcher, Centre for Policy Alternatives, Sanjana Hattotuwa and data scientists Yudhanjaya Wijeratne and Raymond Serrato, based in Germany.

The analysis began after a number of prominent Twitter users began noticing a sudden influx of new followers, beginning from late March 2018 and leading into April, many of them which had no bios, no tweets and often only used the default profile picture.

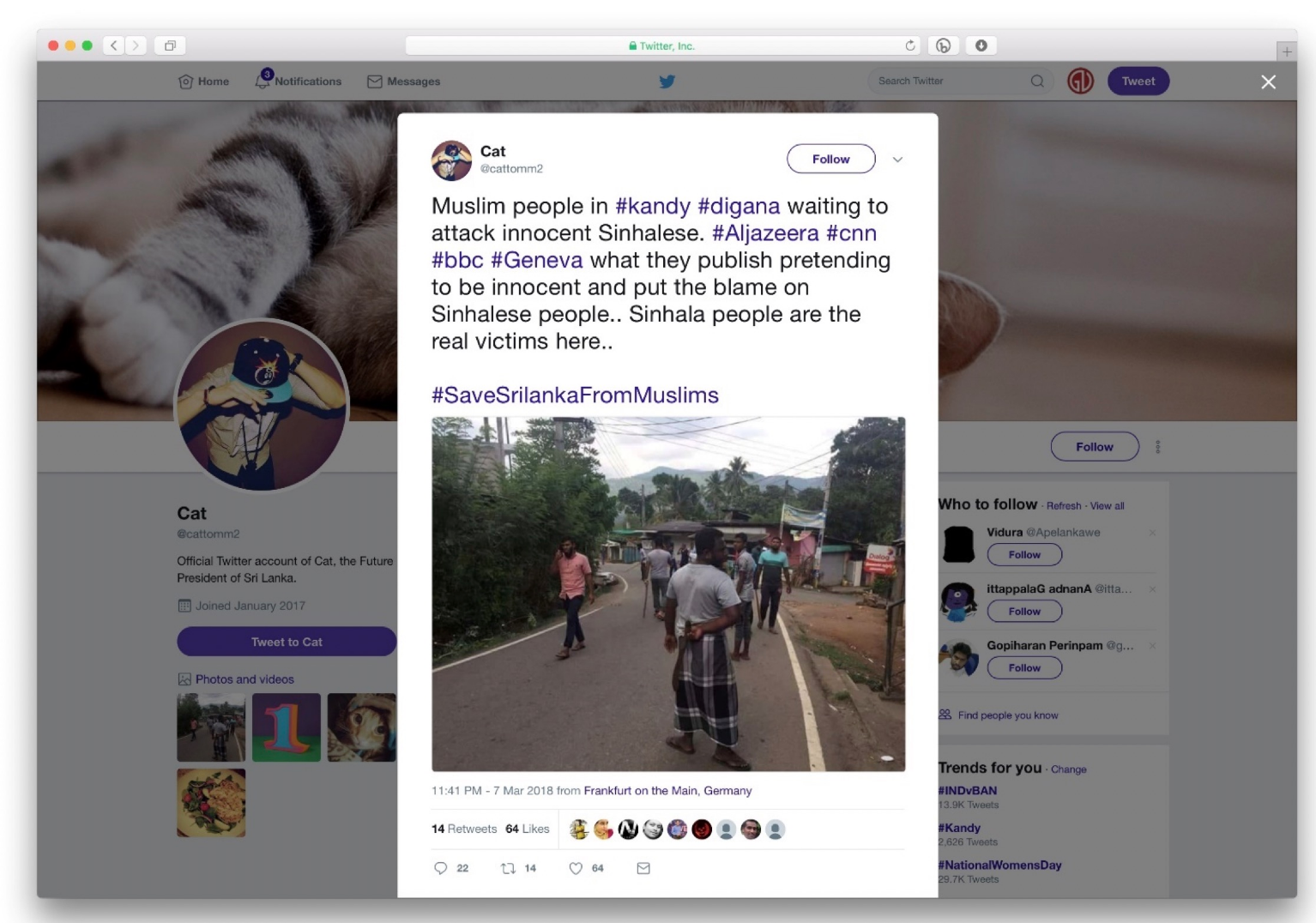

Shortly before, one tweet in particular shared at the height of violence in Digana, Kandy, caused Groundviews to tweet about the importance of checking the veracity of content shared on Twitter before sharing.

The tweet, still online, from 7 March 2018, has at the time of authoring this report been liked 112 times, and retweeted 23 times. The tweet suggests that a gang of Muslim men are on the street, waiting to attack Sinhalese. Not a single other person on the ground, media, Police or government backed this claim or reported on the same issue or incident at the time, or even after. Tellingly, the tweet itself is published from Frankfurt, Germany, a fact many who saw and responded to the tweet on mobile or desktop would not have been attentive to. Though not impossible for someone out of Sri Lanka to report on what is going on inside the country, even a cursory reading of the account suggests it is not one that can be taken seriously – with tweets and retweets of textual gibberish and photos of kittens, teddy bears and food.

In this context, the sudden influx of Twitter followers merited further investigation. Around this time, it was discovered that this phenomenon is not unique to Sri Lanka – Twitter users in Myanmar, Cambodia, Hong Kong, China and several other South East Asian countries also reported a sudden surge in followers. Twitter for its part did not initially respond to these reports, despite the issue being flagged in the media several times.

The Financial Times also covered the surge in bot account activity in South East Asia

Subsequently, a spokesperson said they were looking into the issue, and they would take action against any account found in ‘violation of Twitter’s rules.’

For the first time in the Sri Lankan Twittersphere, Groundviews took the step of making public its block list, which other users could import.

Drama around #NoConfidenceMotionSL today overshadows serious, significant spike in #fake/bot account creation & spread. To help users deal with the influx of bot accounts, we are making public our block list https://t.co/6f9tA60Omr #lka #srilanka @Policy

— Groundviews (@groundviews) April 4, 2018

Even this measure though was not enough to address the high frequency with which new, fake accounts were being created, attaching themselves to prominent Twitter users in Sri Lanka.

Twitter users flagging the sudden influx of followers

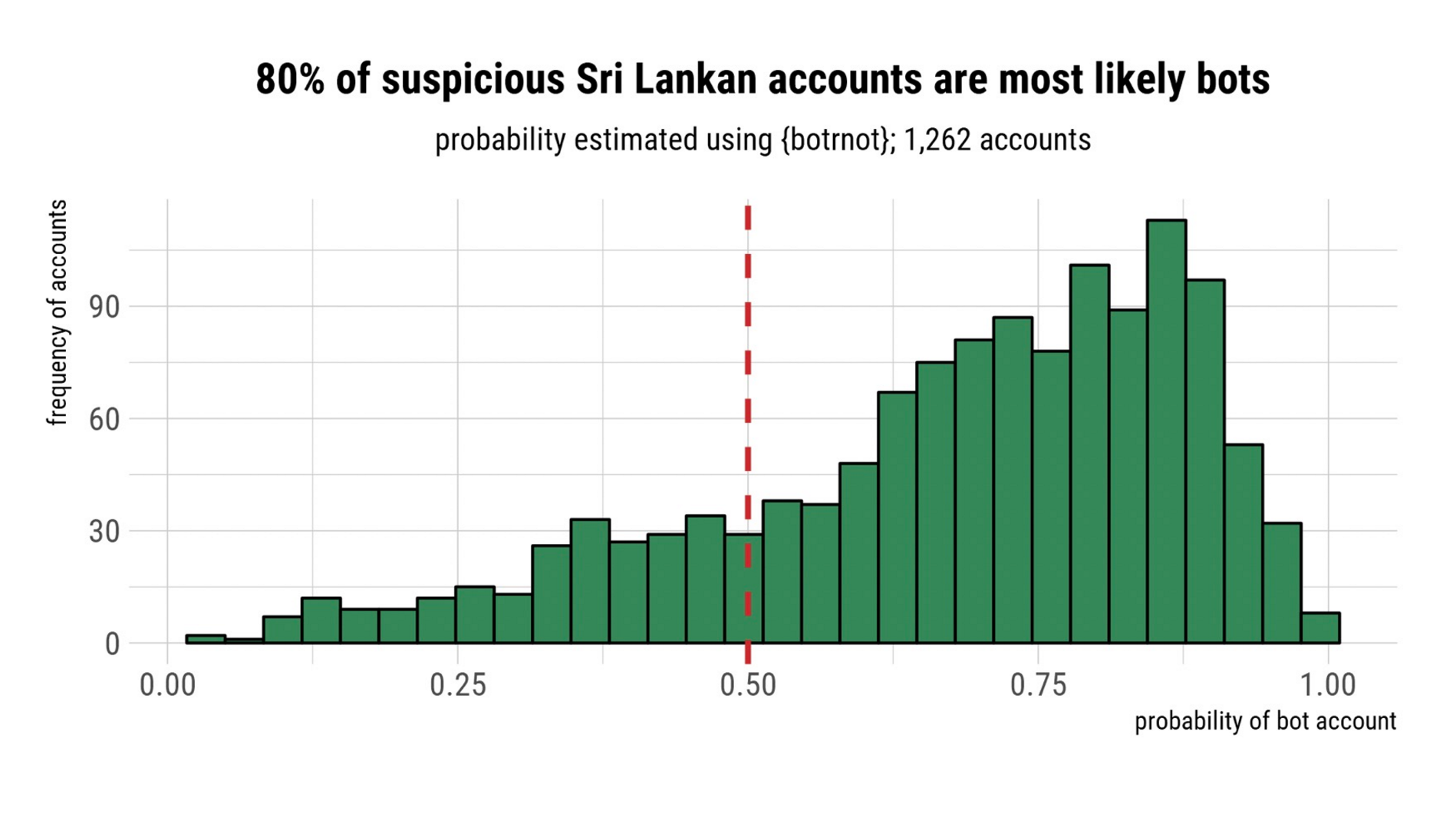

With the help of two data scientists, and looking at over 2000 accounts, it was found that many of these suspicious accounts were bots.

Visualisation showing that the majority of suspicious Twitter accounts flagged are probably bots

Visualisation showing that the majority of suspicious Twitter accounts flagged are probably bots

The accounts targeted including leading diplomats, Ambassadors based in Sri Lanka, the official accounts of diplomatic missions, leading local politicians, the former President of the Maldives, media institutions, civil society organisations and initiatives, leading journalists and cricketers. This matched the profile of the accounts targeted in other South East Asian countries as well, which included journalists, academics, activists, entrepreneurs and UN officials.

Visualisation of some of the accounts targeted

Considering bots are now a permanent feature of Sri Lanka’s Twitter landscape and will likely grow in scope and scale leading up to elections or a referendum, it is important to ask how to address the issue at scale, given the number of citizens – directly connected as well as influenced by those connected – involved.

We publish below the summary of the report.

###

Starting late March, Groundviews and other Twitter users in Sri Lanka began noticing a tsunami of Twitter accounts with no bios, no tweets and the default profile picture following them.

Immediately evident were interesting characteristics, not unlike the bots and fake followers anchored to account of Namal Rajapaksa. The bots had Sinhala, Muslim and Tamil sounding names. Many of the profiles were the default Twitter profile image, but many of the female accounts had photos lifted from public profiles of other individuals. Given the scale and scope of the infestation, Groundviews, for the first time in the Sri Lanka Twittersphere, took the step of making public its block list, which other users could import. Even this measure though was not enough to address the high frequency with which new, fake accounts were being created, attaching themselves to prominent Twitter users in Sri Lanka.

Preliminary analysis of 1,262 accounts, a subset of the larger dataset we were working with, indicated that the majority of suspicious accounts following Twitter users were bots. A visualisation of the number of accounts targeted by the bots revealed that leading diplomats, Ambassadors based in Sri Lanka, the official accounts of diplomatic missions, leading local politicians, the former President of the Maldives, media institutions, civil society organisations and initiatives, leading journalists, cricketers and other individuals were amongst those who had large bot numbers of bot followers.

The authors scraped the details of these 2,229 people followed by the bots: their names, their locations, languages, public details, account creation dates, number of followers, amongst other details, and their last 100 tweets. Collectively, this gave us 214,013 items and around 71 variables.

Considering bots are now a permanent feature of Sri Lanka’s Twitter landscape and will likely grow in scope and scale leading up to elections or a referendum, it is important to ask how to address the issue at scale, given the number of citizens – directly connected as well as influenced by those connected – involved.

Even with its limited scope and data, this report is a clear snapshot of the political landscape we now inhabit, and projects in the future real dangers that result from just the visible investments made around key social media platforms, which are today the key information and news vectors for a demographic between 18-34.

For the full report, click here.

Editor’s Note: For an earlier investigative article looking at Namal Rajapaksa’s strategic use of trolls and bots for digital propaganda, click here.