Featured image courtesy Reuters

Recently, Groundviews compiled a timeline of all the statements made by the Government in terms of the participation of foreign judges in a judicial mechanism.

The timeline shows that over the past two years, there have been contradictory statements from within the same Government on this score. The inclusion of foreign judges has become an increasingly contentious topic, particularly following the recent UNHRC session in Geneva, which saw Sri Lanka co-sponsoring a resolution amounting to a technical rollover, allowing two more years to fulfill the provisions laid out in the UNHRC resolution.

Most recently, President of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka U R de Silva, speaking to the media, opposed the inclusion of foreign judges in a judicial mechanism.

“Our position is that it is not necessary for us to invite foreign judges. We have all the material with us in terms of judges, who know what the Sri Lankan position is, and know the laws pertaining to the exercise [of a judicial mechanism],” De Silva told Groundviews. “If we are going to invite foreign judges, it’s not just a problem, but an insult to the judiciary.”

It is notable that at the press event, de Silva had said that the Bar Association’s official stance would be “announced after a meeting of its executive committee.”

Speaking further, de Silva said that there should be a specific provision in the Constitution, inviting foreign judges to participate in any judicial mechanism. “That is why the President and Prime Minister have categorically said that they can’t do so,” he added.

However, other members of the legal fraternity have differing opinions.

“The conversation on legality is really a proxy for the real conversations which we should be having,” Attorney-at-law and co-founder for the South Asian Centre for Legal Studies, Niran Anketell said.

Anketell recently pointed out that the Constitution is silent on the issue of judge’s nationality, although it is explicit on the nationality of other offices such as that of the President and Parliamentarians. The only requirement is for an Oath, which unlike the one taken by new citizens in the United States, does not require disavowal of loyalty to other countries. “Here, you have to pledge to be loyal to Sri Lanka and uphold and defend the Sri Lankan constitution. In my view, there is no bar to a foreigner taking such an Oath, if they want to do so,” Anketell pointed out.

Further, looking at UN Resolution 30/1, the Government had made certain obligations. While many had claimed that OP6 of the resolution had only allowed for foreign personnel in an advisory capacity, OP1 had clearly incorporated the recommendations by the OISL report, which called for a hybrid court.

Even with the assumption that the inclusion of foreign judges was illegal as de Silva and others, including the President and Prime Minister had claimed, the Government had made it clear that setting up the special court would follow a process of constitutional reform. As such, if they wanted to include foreign judges, they only had to amend the constitution to do so. “This argument on judges is masking a deeper question, which is whether the legislation for a special court inclusive of foreign participation is desired or not.”

“Foreign judges are not a panacea, and it is even conceivable that some local judges may be more credible than handpicked foreign ones. However these conversations need to be had. What is most concerning is that the lack of clarity from the Government in terms of their doublespeak – saying one thing in Geneva and another in Colombo – has dampened their credibility,” he added.

“The government has made very concrete guarantees, and the onus is on the Government to ensure a credible process. I think that’s how it’s going to be judged. Is there going to be a meaningful judicial process: Who are the local judges, prosecutors and investigators going to be? They have set themselves a high bar” Anketell said.

Speaking to Sri Lanka’s capacity to create a judicial process on accountability, Anketell said that processes such as these were “extremely resource intensive”. In Cambodia, for instance, the prosecuting team was made up of more than 20 lawyers, who had been trained in either international law or international criminal law. “There are credible Sri Lankans with the necessary expertise to be found domestically, but the question is, can the regular system afford to let go of them, and are there sufficient numbers to be found at home?” Anketell said.

Research Director, Verité Research Gehan Gunatilleke said that the question on foreign judges needed to be considered in two parts; firstly, whether the Government should include foreign judges, and secondly, whether or not doing so was within the bounds of the constitution.

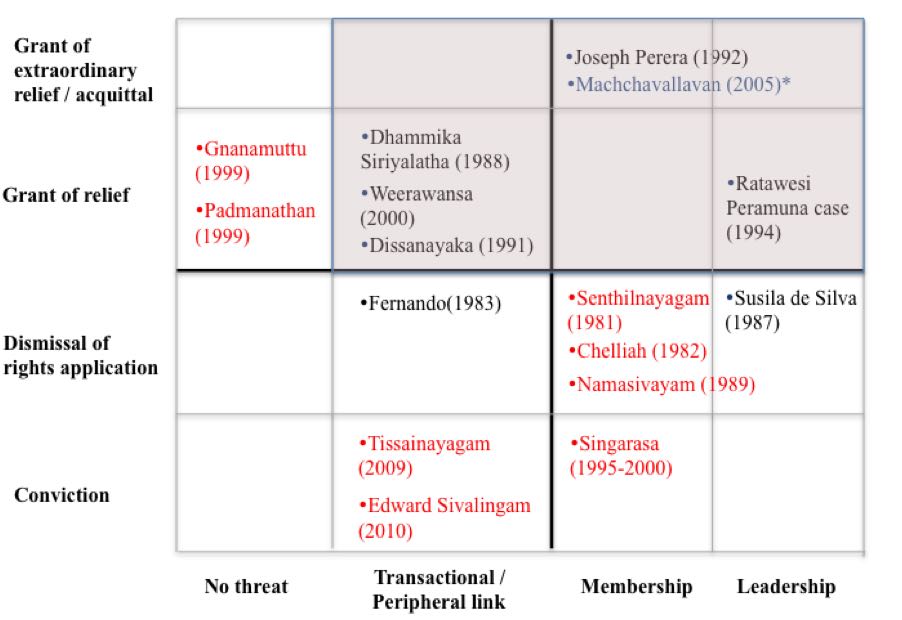

Gunatilleke co-authored “The Judicial Mind” a book that examined how the Sri Lankan judiciary had dealt with minority issues – focusing specifically on cases dealing with arrests and detention (see page 217 for the chapter on minorities). “There is a consistent pattern dating back to the 1970s, where judges have been deferential to national security interests,” Gunatilleke said. This resulted in prejudice towards Tamil litigants and the accused in Fundamental Rights cases under the Prevention of Terrorism Act, and dealing with arrests and detention.

Infographic from “The Judicial Mind” examining a number of cases involving minorities.

“There is a historical case to be made that the local judiciary is systemically prejudiced when it comes to any case concerning national security. In that context, it is difficult to see a purely local judicial mechanism deliver accountability for war crimes.”

“The supposed restoration of the independence of the judiciary doesn’t displace this insistence, because it is related to a much longer historical precedent than the post-war period under the Rajapaksas,” he added.

Gunatilleka concurred with Anketell’s position that there was no constitutional bar to the participation of foreign judges. “Mr de Silva is making an assertion without referring to any provision in the constitution… The question is not one of constitutionality but of political will.”

For his part, President Sirisena has remained firm in his determination not to include foreign judges.

The question remains whether Sri Lanka will be able to set up a mechanism that will provide redress to those affected by the conflict. Even today, families of the disappeared are holding protests in an attempt to get answers for the whereabouts of their loved ones.

Day 34:Relatives of #DisappearedSL in #Vavuniya continue their protest saying they will never give up till they are given substantial relief pic.twitter.com/BUb7UxXXQo

— Garikaalan (@garikaalan) March 29, 2017

Others are filing RTI requests in a desperate attempt to get some response from the state, or are struggling to rebuild their lives with little to no state support. They deserve closure, support and answers. It is as yet unclear when they will receive relief.

Those who enjoyed this article might find “Flip-flopping on accountability – a timeline” and “A historic moment: Breaking down the CTF report” enlightening.