“You’re an Internet addict!”

That is what a retired professor of mass communications told me publicly at a university media conference four years ago. I was a bit taken aback as he had no clinical training to make such assertions.

The basis for his ‘diagnosis’ was simple and simplistic. I had just told my audience how I was spending increasing number of hours each day online engaged in various functions like searching, reading, blogging or tweeting. He felt that it was rather excessive (= wasted?), compared to his own total use of Internet which was limited to dealing with emails (on which he spent an average of half hour a day).

We agreed to disagree, and our audience was divided. I wish, though, the amiable don either updated his knowledge — or kept his mouth shut on matters he knew little about. (Internet addiction is not measured by the duration spent online.)

That little encounter highlighted a much larger problem: many opinion shapers and decision-makers in Lankan academia, public administration and education sector remain ill-informed and yet highly prejudiced about digital and web based technologies.

My on-going interactions with our university teachers of journalism or mass communication reveal how some of them love to bash the web and mobiles phones – even as they use these technologies themselves! There is no research or analysis behind such negativity – the worthies just know it’s bad for you and me!

Even worse, they sometimes cite their own dubious studies to justify this stand. One example is a ‘survey’ by a journalism professor at a leading University that suggests a link between rising divorce rates and growing popularity of Facebook in Sri Lanka! Some Sinhala language newspapers reported this ‘finding’ rather gleefully, probably because it fit their own moralistic worldview. Yet my repeated queries on that study’s sample size, methodology, assumptions and limitations went unanswered. That was two years ago.

With 30 per cent of our population now using the Internet, it is no longer a peripheral pursuit. Neither is it limited to cities or rich people.

So we urgently need more accurate insights into how society and economy are being transformed by these modern tools.

Disappointingly, many Lankan sociologists hesitate to study the socio-cultural impacts of new media – perhaps out of a (misplaced) fear of these issues being ‘too technical’? Meanwhile, IT engineers and other ‘techies’ involved in the digital infrastructure are not much concerned with societal issues arising from their work.

This disconnect has led to dangerous gaps in knowledge and policy formulation. Some are demanding ‘strict regulations’ without evidence. Public discussions about the web and digital media easily get polarized between those who uncritically embrace and others who habitually demonize anything modern or foreign.

I stand in the middle, and often get caught in their crossfire…

Acknowledge Problems

Such confusion is not unique to Sri Lanka. But as a democracy recovering from a decade of authoritarianism, we need to be especially careful how public sentiments based on fear or populism can push policymakers to restrict freedom of expression online. The web has become the last frontier for free speech when it is under pressure elsewhere.

When our politicians look up to academics and researchers for policy guidance, the advice they often get is control or block these new media.

Instead, what we need is more study, deeper reflection and – after that, if really required – some light-touch regulation.

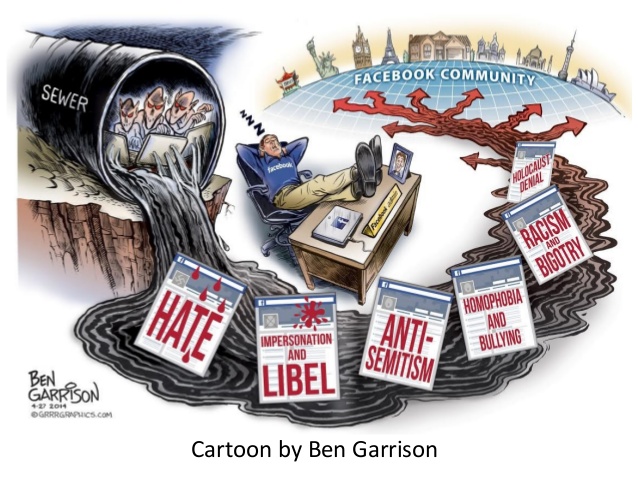

To be sure, there are certain problems arising from new technologies – some predictable, and others not. These include cyber-bullying, hate speech, identity theft through account hijacking, trolling (deliberately offensive or provocative online postings) and sexting (sending and receiving sexually explicit messages, primarily via mobile phones).

Some of these concerns have been studied recently by advocacy groups. They focused primarily on certain unhealthy aspects of Facebook, the most widely used social media platform (3.5 million Lankan accounts, and counting).

Consider these findings:

- Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) did the first study on hate speech on Facebook in Sri Lanka (Liking Violence, Nov 2014). It documented, with evidence, growing online hatred towards religious or ethnic minorities, women, LGBT (gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender) communities, human rights defenders as well as investigative journalists.

- Women and Media Collective (WMC) has conducted another study, as yet unpublished, on Facebook hate speech and its relation to the sexual, reproductive and health rights of women and girls in the local context. It shows how sidelining or harassing women is increasingly happening online, as it has been going on for decades in the physical world (a.k.a. ‘offline’).

- Meanwhile the Grassrooted Trust, set up to provide “a safe space for marginalized communities online and in the real world”, has documented a growing illicit trade of digital photos of Lankan schoolgirls in various stages of undress or intimacy. These have been swapped using chat applications or shared through facilities like DropBox, leading to cyber-exploitation and blackmail. Perpetrators are mostly schoolboys themselves.

These findings are not pretty, and some of them outright damning. But bans, blocks and penalties alone cannot deal with these or other abuses. As Shilpa Samaratunge and Sanjana Hattotuwa, co-authors of the CPA study on hate speech noted emphatically, “Ultimately, there is no technical solution to what is a socio-political problem.”

Living in Denial?

An extra hurdle in getting there is lack of awareness at all levels of society, including among information technology (IT) professionals. Some of them wonder what the fuss is all about.

About two years ago, I was on a panel on Internet and innovation when a fellow speaker, an Internet pioneer of Sri Lanka, dismissed hate speech online as something hyped up by social activists.

In his view, anyone who doesn’t like such ‘unpleasantness’ should avoid going on social media platforms. Using a metaphor, he said: “If you go to an area like Maradana in Colombo (known for its urban chaos) and bump into someone, you are very likely to get shouted at…so why go there at all?”

I whole-heartedly disagreed, and argued that both the government and society shared the responsibility for making all parts of a city safe for all citizens. The same principle applies online: we need to work on creating a safer and more meaningful Internet experience for all.

Alas, avoidance appears to be the easy option chosen by certain middle class parents in Sri Lanka who are raising children deliberately denied Internet (while parents themselves use it). Oh sure, it is their parental prerogative. But they have no right to object to more liberal parents allowing their kids grow up digital.

A journalist friend tells me how his teenaged son is the only kid in his class at a leading boys’ school in Galle who is allowed Internet access and mobile phone use at home. It’s not an affordability issue: other parents have apparently banned their kids from using these ‘evils’!

Recently, his son came first in a class project on outer space – simply because the boy accessed NASA websites for latest information and images. Other parents had protested that the winning boy had an ‘unfair advantage’.

In the Puritanical Republic of Sri Lanka, is a youngster’s Internet use – even for educational purposes – now being likened to using performance enhancing drugs in sports? What next? Banning Internet access for anyone under 18?

Parental or governmental bans are not wholly effective in any case. Growing up in the pre-web days of the 1970s, I recall how parents banned us from reading comics or chitrakatha papers – that decade’s much-maligned ‘evil’ to ‘corrupt young minds’. That only added an extra kick to our surreptitious reading of the ‘banned’ material…

Like many other modern technologies and media, navigating the web and digital tools involves a careful balancing act at personal, household and societal levels. We need cautious engagement, not blind rejection.

Living in denial of cyber hazards won’t take us forward. On the other hand, overstating the dangers and forcing bans or blocks can push our society back to the feudal ages — when knowledge was monopolized (by elites and clergy) and free expression deprived.

Safer and Saner Internet?

So what is to be done? There are no easy answers or quick fixes.

As a long-standing chronicler of our information society, I can suggest three priority responses.

First, let’s recognize that the cyber world — including social media – are mirrors that reflect our physical world to a great extent. Some among us have taken their prejudices and depravations online, taking advantage of the anonymity and pseudonymity that the web allows. But the hatred, insecurities, jealousies and other sentiments are all rooted in the offline world. As Dr Harini Amarasuriya, a sociologist with the Open University, has urged, ““We have to start asking not what is wrong with Facebook but what is wrong with our society!”

Second, we must acknowledge that complex problems cannot be solved by simplistic or knee-jerk responses. Example: over-reacting to public outcry over a schoolgirl’s tragic suicide, the former President banned all school kids from taking mobile phones to school (no debate allowed). Some schools have banned their students from having a Facebook account (many do anyway, under false names). Bans only create scarcities, black markets and intrigue, and are wholly counterproductive.

Third, we need rigorous and dispassionate research on how digital technologies are changing our society — for better or worse. Evidence of misuses need context and open debate so that policy and regulatory responses can be proportionate and reasonable.

We cannot allow a few overzealous individuals to force society throw the digital baby away with the bathwater.

True, the country’s computer and telecommunications related laws are not fully geared to protect citizens going online. But what we need are measured and nuanced responses — and not draconian laws that can stifle the inherently irreverent character of online conversations.

Free Speech online

At a time when boundaries of free speech are being redefined in the age of social media, Sri Lanka’s current democratic recovery needs more – not less – spaces to question, critique and challenge governments and all others in authority. This includes not just politicians and officials but also military generals and clergy.

There was a time when mainstream media did just that, and forcefully. But after years of self-censorship and partisan reporting, many have forgotten how to be watchdogs of public interest.

The web offers a partial solution to this journalism deficit. Already, Sri Lanka’s blogospheres and twitterspheres are vibrant and delightfully cacophonous. Thousands of users are asking many inconvenient questions and debating a whole array of current issues, some of which are deftly avoided by most mainstream media (e.g. persistent caste-base in Sinhala and Tamil politics; LGBT rights; need for a secular state, etc.).

We can and must shape the new cyber frontier to be safer and more inclusive. But a safer web experience would lose its meaning if the heavy hand of government or social orthodoxy tries to make it a sanitized, lame or sycophantic environment at the same time. We sure don’t need a cyber nanny state.

In my view, enlightened, light-touch regulation coupled with enhanced cyber literacy is the pathway to a better digital future. Before filling the laws’ gaping gaps for better protections, we netizens and other citizens must discuss what is being proposed for our own good.

###

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene has chronicled and critiqued new media since the mid 1990s. He blogs at http://nalakagunawardene.com, and is on Twitter as @NalakaG. A compact version of this essay was published in Weekend Express newspaper.