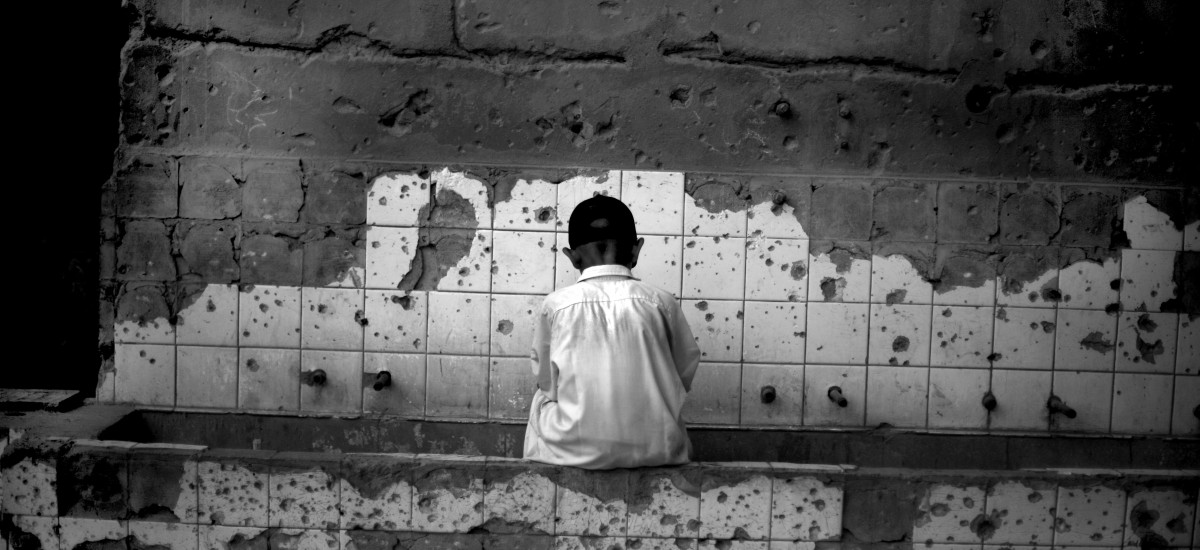

Photo courtesy Understanding the Age of Transitional Justice

Last week, SACLS released a report titled “From Words to Action: A Road Map for Implementing Sri Lanka’s Transitional Justice Commitments”. This report unpacks the TJ package contained in UNHRC Resolution 30/1, classifies the commitments made by the government of Sri Lanka through the co-sponsoring of Resolution 30/1, and breaks them down into tangible, operational, and objectively verifiable steps.

After investigative missions—such as the OISL—report to the UNHRC, the latter often mandates mechanisms to monitor the implementation of the recommendations issued by investigative bodies, or of the recommendations contained in UNHRC follow-up resolutions. This was done for example with respect to the situation in Darfur and as a follow-up to the Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Operation Cast Lead carried out by the Israeli military in the Gaza strip in December 2008-January 2009. As an alternative, or in addition, the UNHRC often mandates OHCHR to monitor and publicly report on progress. It is in this context that Resolution 30/1 tasks OHCHR with “assessing progress on the implementation of its recommendations and other relevant processes related to reconciliation, accountability and human rights” in Sri Lanka.

Though not always undertaken systematically, mechanisms tasked with monitoring progress in the realm of Transitional Justice (TJ) sometimes devise roadmaps of the kind prepared by SACLS. Such roadmaps serve as a tool for constructive engagement with the government concerned. It is therefore unfortunate that no roadmap of the kind issued by the experts group on Darfur was issued and released publicly by OHCHR. Unlike the government of Sudan, the government of Sri Lanka committed itself (though its decision to co-sponsor Resolution 30/1) to implement the recommendations contained in this resolution in full. Therefore, a roadmap proposed by OHCHR would have stood a reasonable chance of being agreed upon by Sri Lanka, at least partially. This would also have reassured the public as to the level of OHCHR’s engagement in the process.

While OHCHR is due to report orally to the UNHCR in June this year, a comprehensive assessment of progress will only take place in March 2017, one and half years after the government committed itself to the TJ package contained in Resolution 30/1, and more than two years after the change of government. Such a time frame is plainly sufficient to devise and start implementing a TJ policy. Therefore, if the government stands by its commitments, OHCHR will be in a position to report on significant steps taken by the government. However, if the process stalls in the interim, a course correction may not be possible at that point in time. As time passes, fatigue with respect to TJ is likely to set in. In addition, at home, the government is expected to expend its limited political capital in constitution making and other reform agendas. As Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera himself wisely notes, the most controversial reforms should be implemented as quickly as possible after a new government accedes to power in order to capitalize on fresh momentum. For this reason, a systematic monitoring of progress must not be delayed.

Within each of the four TJ pillars (truth-seeking, prosecutions, reparations and guarantees of non-recurrence), there is room for policy choices that are best decided upon after consultations take place. However, a number of commitments made by the government in October may be operationalized in the interim. Indeed, while UNHCHR recommendations are sometimes purposely obscure, due to the political negotiations that invariably take place in interstate forums such as the UNHRC, they, more often than not, refer to preexisting and well-established States’ obligations under international law. The breakdown of the commitments made in Resolution 30/1 into intermediary steps, which are required as a matter of logical sequencing or as a matter of international law, shows that many steps may be implemented through administrative action and are not particularly politically costly. These include measures in areas that require immediate progress such as the release of lands and the repeal of the PTA. In addition, as the SACLS report sets out, these also include early administrative steps with respect to more complex and politically sensitive issues such as the institutional design of a special court.

The breakdown of the recommendations into an actionable roadmap also helps narrow down and identify steps that are expected to meet with significant challenges as well as institutions and individuals that may derail the process. If major political roadblocks hinder the implementation of some TJ measures, it may be useful to pursue a sequential approach. The concept of sequencing in Transitional Justice was introduced as an alternative to the false dichotomy between peace and justice. As explained by the UN Secretary-General “justice, peace and democracy are not mutually exclusive objectives, but rather mutually reinforcing imperatives. Advancing all three in fragile post-conflict settings requires strategic planning, careful integration and sensible sequencing of activities”. Sequencing is essentially a political tool to overcome obstacles to justice in an unstable post-conflict situation. However, if politically feasible, prosecutions ought not to be delayed unnecessarily. Unwarranted delay may impede rather than catalyze TJ. Sequencing Truth Commissions to precede trials may have worked in countries where trials were legally and politically impossible at first. However, this does not mean that TRCs must always precede trials. In fact, implementing trials and TRCs in tandem could help both mechanisms complement each other, as in the case of Sierra Leone and East Timor.

Many in Sri Lanka, and some amongst the diplomatic community are now under the impression that the commitments made by the government of Sri Lanka were too far reaching and too ambitious to be successfully implemented within a limited time frame. The program of reforms to which the government committed itself and its end goal are indeed very ambitious. As Minister Samaraweera underscores, the commitments made by the government in October last year could, if implemented, help Sri Lanka “come to terms with its past if we are to forge ahead and secure the future that Sri Lankan people truly deserve”. However, the breakdown of the commitments into an actionable roadmap shows that many steps including some pertaining to politically sensitive areas such as the pursuit of criminal justice for international crimes may be implemented within a short time frame. It is therefore important to hold the government accountable to each of these intermediary steps that will pave the way for the successful implementation of Resolution 30/1.