Featured image courtesy Amalini de Sayrah

Last week saw the usually sleepy town of Galle come to life with the Galle Literary Festival. In a celebration of all things literary, Colombars descended upon the town for a dose of culture. And there were, indeed, some high points.

The Festival has constantly been dogged with allegations of being overly elitist; with some of its lunches and dinner events being priced high enough to bar the average citizen (or indeed, resident of Galle) from entry.

However, it was refreshing to see many more free events compared to previous years. From dance performances, to panel discussions and film screenings – not to mention a beautiful melding of Sufi, gospel and jazz music – there was a lot for people to take in.

Perhaps one of the most informative free sessions was one on Tamil poetry, headed by poet S Pathmanathan who has translated the work of several Tamil poets into English.

In the hour long talk, Pathmanathan explained that Tamil poetry evolved from dealing with topics such as caste and dowry to love and the darkness of war. Before reading each work, Pathmanathan made sure to place it in context, explaining cultural nuances which otherwise might have been lost. A true moment of poignancy was achieved when Pathmanathan read his own poem, detailing the loss that comes with displacement from one’s home. Pathmanathan had to flee from his village in Weligama when the LTTE ordered all residents to evacuate. In his haste, he left his dog, Blackie, behind.

Poet S Pathmananthan on the loss of his pet due to displacement at #glf2016: https://t.co/iUMYgPO0s0 #lka #SriLanka pic.twitter.com/QNNmkVPg2p

— Groundviews (@groundviews) January 21, 2016

Pathmanathan says that he chooses to translate by ‘sense-groups’ focusing on conveying the meaning of the poetry rather than capturing the exact rhythm or language used. Perhaps in this, some of the beauty is lost, but the poems were nevertheless powerful, especially those dealing with war.

There were also several free sessions on Sinhala literature: focusing on the tradition of Sinhala poetry in the Selalihini Sandeshaya, for instance, as well as discussions on more contemporary Sinhala literature. Ramla Wahab Salman also led a talk on the histories of Muslims in South-West Sri Lanka.

In this sense, the Festival was far more inclusive than it has been in previous years, attempting to engage festivalgoers on a variety of cultural and literary traditions. It was a shame that some of these weren’t better attended.

One of the most packed sessions was that of Bengali author Amitav Ghosh, who penned the well-known Ibis trilogy. In an entertaining session, Ghosh delved into the nuances of Sri Lanka’s demotic English, “Every third word was men, and every fifth was bugger!” he laughed, reminiscing about schooling at Royal College. This interest in colloquial English is reflected in his books – Ghosh often expending considerable effort to capture the different nuances of spoken English across different provinces.

Much of the Ibis trilogy focuses on the Opium wars between England and China – and Ghosh revealed that a squadron from Trincomalee had also been deployed to fight in the Wars. Ghosh’s talk was peppered with little bits of trivia like this, displaying his abiding passion as a researcher.

Equally crowded was Sonali Deraniyagala’s talk on her novel, ‘Wave’ – the heartwrenching story of her losing her entire family in the 2006 tsunami. Sonali’s talk was raw and honest – she spoke of floating on her back, fighting death, and simultaneously noticing a flock of painted storks flying past. She also spoke with honesty of the anger that often comes with trauma:

Sonali Deraniyagala on the aftermath of the tsunami, and how writing helped save her life #GLF2016 #SriLanka #lka pic.twitter.com/gevBBaY12H

— Groundviews (@groundviews) January 16, 2016

Her talk earned her a standing ovation.

Given that Sri Lanka is transitioning out of war, there were also sessions that dealt with this memory. Omar Musa and Padma Wishwanathan for instance, spoke on trauma, migration and recovery, exploring how migrating to the West can affect new immigrants and their families. In discussing this, they also spoke on the ways storytelling can bring a sense of resolution to unsolvable issues.

"Imp to have safe spaces for dangerous thoughts" Omar Musa on reconciliation. How true is this in #SriLanka ? #lka pic.twitter.com/4by1dOiAhQ

— Groundviews (@groundviews) January 15, 2016

Authors Rohini Mohan and Samanth Subramaniam also spoke on their observations of Sri Lanka’s conflict, from an Indian perspective. They explored the sense of alienation and guilt they felt as outsiders, documenting a situation of conflict:

#SriLanka war and peace through Indian eyes: Rohini Mohan talks about a former female combatant #lka pic.twitter.com/lxGQNYbCoN

— Groundviews (@groundviews) January 16, 2016

Samanth Subramanian on the tension felt as an outsider interviewing conflict affected Sri Lankans #lka #srilanka pic.twitter.com/78tOKT7mhJ

— Groundviews (@groundviews) January 16, 2016

Yet apart from these interesting snippets, was there anything substantive? Is the GLF a true portrayal of culture and literary tradition?

Placing Culture In Context

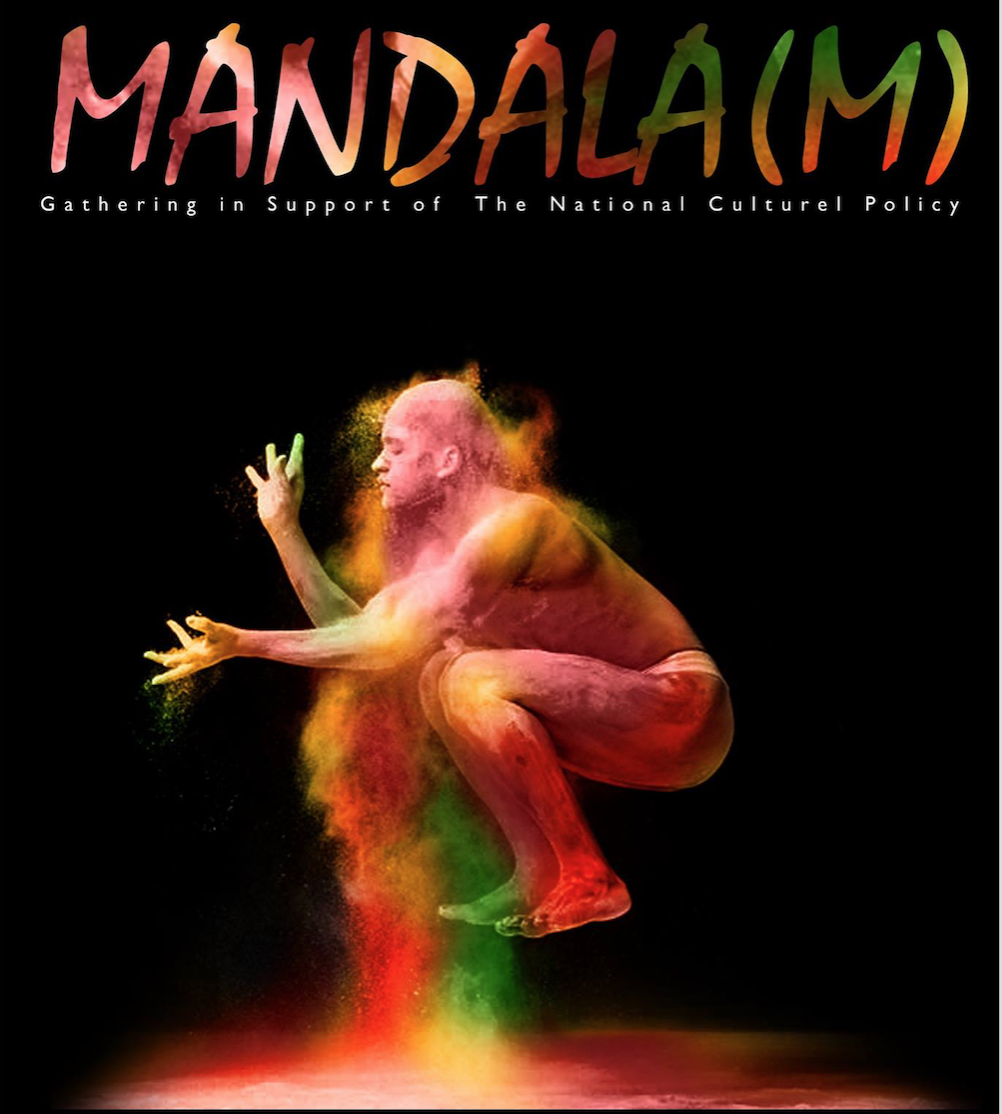

On January 7, the Arts and Cultural Policy Desk, an independent initiative of artists and intellectuals, hosted ‘Mandala(m)’ an event bringing artists and intellectuals alike together, to discuss the need for a National Cultural Policy.

The event saw puppeteers, musicians and scholars come together to give an evocative series of talks and performances, all centred around culture.

Perhaps the best food for thought came from actor, director and theatre personality Sinniah Maunaguru.

If we research into the history of human life, we see that all human communities have always moved from place to place in search of food and shelter… Due to such journeys and displacements, every group was intricately connected to other groups. They mixed with each other through wars, friendships, commerce and trade, and through curiosity and travel… When we look at this situation, we see that a culture is not unique… Over time, history has shown that, in fact, the basic character of a living culture has been its ability to change and grow.”

In short, culture is evolving, and draws from many communities and traditions.

In this sense, the GLF’s attempt to be more diverse this year is appreciated. This was reflective in the literary awards given out, too – the inaugural Fairway National Literary Awards saw awards going to Sepali Mayadunne in the Sinhala category, for Maha Sami. The English award went to Rizwana Morseth de Alwis for ‘It’s not in our stars’ and Ayathurai Santhan ‘Rails run parallel’ jointly. The 2016 DSC prize for South Asian literature went to Indian author Anuradha Roy, for her novel Sleeping on Jupiter.

The expansion of the Festival from Galle to Kandy and Jaffna was also a welcome move, particularly as events for the latter will be free of charge.

Yet the GLF still fell short – at least in terms of inclusivity. The festival-goers were still mostly Colombars, many of whom were there to see and be seen rather than to learn and engage. Many of the international author’s panels were also ticketed events – barring the public, especially locals in the area, from attending. While there are costs involved in putting up such an event, this remains an unresolved issue – one which prevents fostering the culture of embracing diversity and shared learning that the Arts and Cultural Policy Desk envisions.