“Hope to achieve political settlement through adoption of a new constitution. Don’t judge us by broken promises of past” says Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera at UNHRC in Geneva, on 14th September 2015.

The statement in September by Sri Lanka’s Foreign Minister provided a timely frame of reference to appreciate the ‘Corridors of Power’ exhibition. From the security guards at the venue of the exhibition to international constitution building process experts who gathered in Sri Lanka at the time around a workshop on constitutional reform, from students to academics and activists, ‘Corridors of Power’ even before officially opening to the public generated more interest than any project curated by Groundviews and the Centre for Policy Alternatives previously.

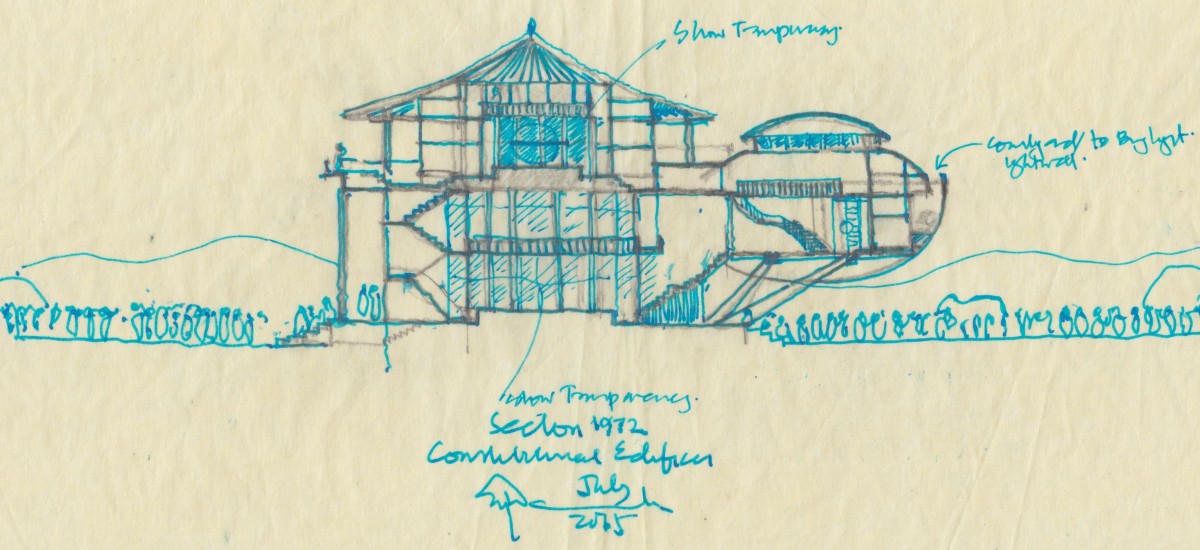

Led by the input of Asanga Welikala, in collaboration with Channa Daswatta, ‘Corridors of Power’ through architectural drawings and models, interrogated Sri Lanka’s constitutional evolution since 1972.

The exhibition depicted Sri Lanka’s tryst with constitutional reform and essentially the tension between centre and periphery. The output on display included large format drawings, 3D flyovers, sketches, and models reflecting the power dynamics enshrined in the the 1972 and 1978 constitutions, as well as the 13th, 18th and 19th Amendments.

To our knowledge, nothing along these lines was ever attempted or created before. In addition to the exhibits on display, each day featured a keynote presentation or panel discussion by eminent individuals, around the topic of constitutional reform in general. All the submissions, including the Q&A session, were recorded and are now available online.

Access them as a playlist here, or download each podcast / recording from here.

- Facebook event page

- Lineup of keynote speakers, including those from Government, respondents and panellists

- Note by Curator (Sanjana Hattotuwa)

~

19th September, The ‘F’ word and the Tamil National Question (Keynote)

In Sri Lanka, merely acknowledging federalism’s role and relevance in constitutional reform risks derailing the process comprehensively. The popular imagination in the South invests in the term an almost unshakeable fear of eventual secession. Years of vilification, negative stereotyping and misinformation have been – at least for those vehemently opposed federalism– successful. Opposition to the idea, and indeed, a clear understanding of its central place in architecting a new constitution, remain, respectively, high and low. On the other hand, much of this opposition stems from the enduring inability of some of federalism’s greatest champions to clearly address some of these fears, and communicate clearly what it is, and is not. Lawyers often assume society writ large to have as good a knowledge of the law as they do, and politicians often support or decry federalism based purely on parochial, electoral gain. Principled, reasoned arguments around federalism, embracing for example concepts that call for the recognition of multiple nations within a united Sri Lanka, are central to meaningful answers around the Tamil national question. And if the Tamil national question is seen as central to realising the democratic potential of Sri Lanka post-war, federalism and its discontent needs to be tackled head on. How can this be done? Given an electorate in the South largely unable and unwilling to support federalism prima facie, what can politicians do to strengthen critical reflection and support? Why is it even necessary, if as some would argue, existing provisions in the constitution are entirely adequate? Can there be meaningful debates around the Tamil national question without resorting to federalism and its promise? If maximalist demands continue without any compromise, and reciprocally, majoritarian fears around secession continue to hold hostage meaningful debates around a new constitutional framework, what is the fate of federalism in Sri Lanka and indeed, if it fails, the prospects around addressing the Tamil national question meaningfully?

- Shiral Lakthilaka

- Respondent: Ameer M Faaiz