So it was a known construction worker cum odd job man who killed senior Lankan journalist Mel Gunasekera.

The man, hunted down within the same day Mel was stabbed to death in her suburban home, was apparently familiar with the place and the family’s routine. When she recognised him, burglar had instantly turned killer.

Case closed? Prima facie, it seems so. But in a land where so many crimes are simply not solved and culprits never caught, some can’t believe this swift and efficient crime investigation. Public trust in institutions, once lost, is hard to regain.

Conspiracy theories won’t bring Mel back. Neither would heart-felt eulogies from her many friends and colleagues. But the latter helps the living: for those who knew and adored her to cope with grief.

Mel would have been bemused by the spontaneous expressions of appreciation that have been pouring out on social media. I can almost hear her say, “Aiyo, what a fuss – get a life, men!”

But life is precisely what has become worthless in our troubled land. Life today is so cheap it can be snapped away at the slightest provocation. Or even without any.

According to police, the killer stole just LKR 1,200 (USD 10) and her mobile phone. No other motive is suspected.

Any death is a tragedy, but what do we make of a killing done for small change and a piece of metal?

As mutual friend Rohan Samarajiva noted: “She should be writing my eulogy, not me hers. The young should not predecease the old. We should have built a country where a young journalist could take the bus with no fear and spend a Sunday morning in her own house without getting murdered. The war brutalized us. Killing became nothing.”

As young blogger and researcher Sharanya Sekaram asked in a tweet: “When we will change from being a nation of the dead and mourned to one of the alive and celebrated?”

Genie runs amok

I don’t think anyone has the answer. Or maybe everyone does.

By coincidence, on the very Sunday morning Mel was snatched away, I was reading Paulo Coelho’s 2011 novel Aleph and came across an unusual quote. It’s an idea the author heard from a man in Tunis: “In our culture, the criminal shares his guilt with everyone who allowed him to commit the crime. When a man is murdered, the one who sold him the weapon is also responsible before God.”

I’m more concerned about immediate culpability than any next-worldly liabilities. Perhaps that Tunisian wisdom applies to us here and now.

Aren’t we all contributors to the dreadful nightmare that has just consumed Mel? It has been nurtured by our indifference, denial (or worse) for decades.

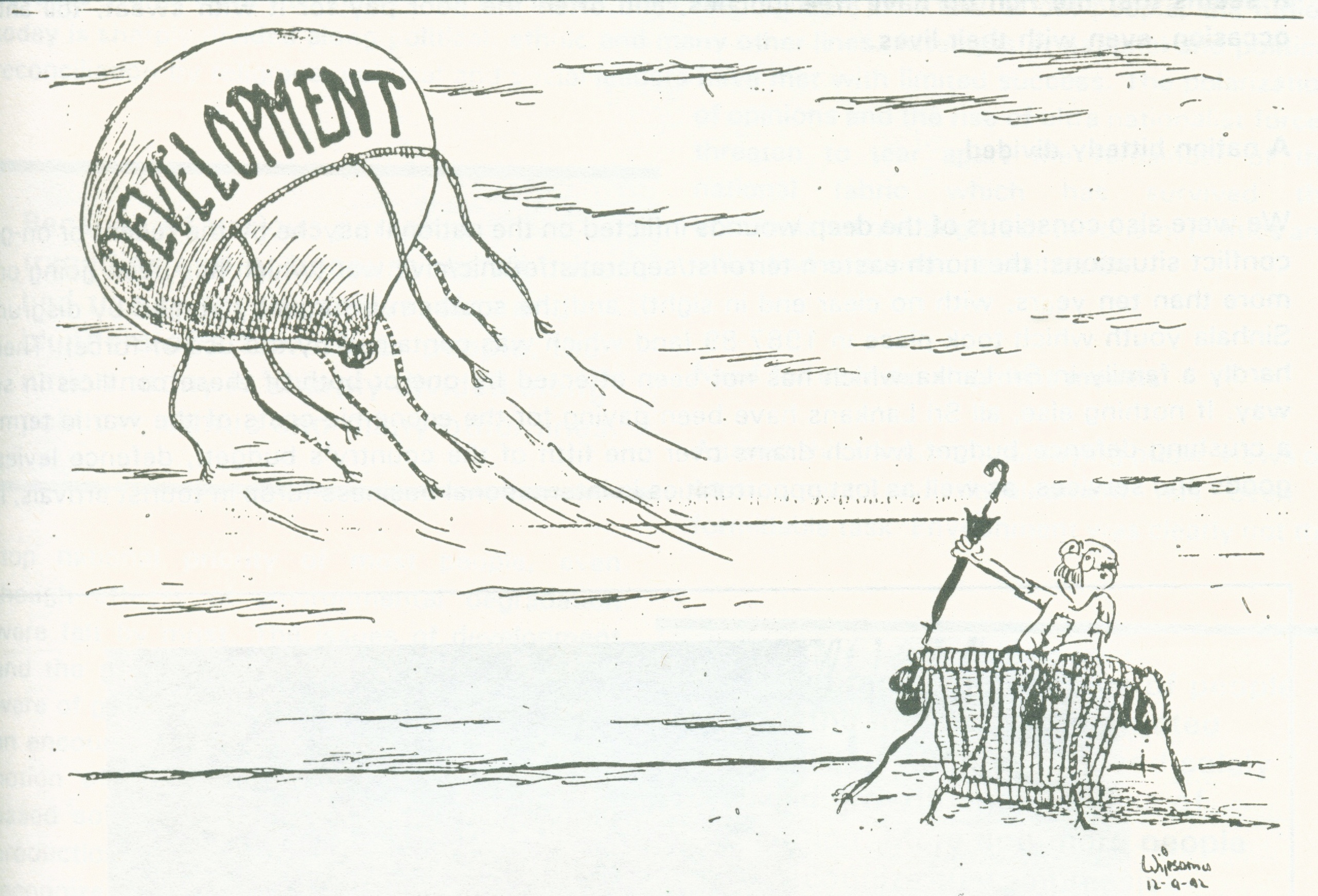

This ‘genie’ is home-grown: a beastly manifestation of our own collective reptilian psyche. For years, it did our bidding. Many among us cheered it while others looked away. The few who questioned — or sounded caution — about brutalising an entire society were shouted down.

Now, nearly five years after the war ended, the big bad genie just won’t behave. It won’t get back in the bottle. It’s running amok, terrorising hapless citizens. Almost like a snake eating itself…

How do we protect ourselves from the phenomenon of our own making? Can we outrun our own shadows?

Fences or walls don’t help much. Elaborate home security systems can give us an illusion of safety. In any case, how many can afford gated and guarded communities? Do we want to live with 24/7 surveillance by private security and have ‘armed response’ — as done in affluent parts of South Africa?

No arrangement is fail-safe. As Samarajiva noted, “we built fortified houses that were death traps should the perimeters be breached.”

Has the breakdown of law and order in Sri Lanka reached such levels that we must now live in eternal fear inside our homes? Are we slowly joining the ranks of the perennially scared residents in sprawling metros like Johannesburg, Mexico City and Bangalore?

What next? Travel only in convoys at night, and start carrying small arms?

Which way forward?

Surely, there must be another way. A bumpy and slow road that would probably be, but explore it we must.

Call it a path of healing, sharing and caring. Researchers might give it more lofty labels like ‘inclusive growth’, or ‘post-conflict transformation’. We can’t leave it to the government alone; individuals and community groups have to play a key role.

The metaphor of roads is apt because we have had a frenzy of road building since the war ended. Oh, we do need to fix the long neglected infrastructure: better roads not only enable movement of people and goods, but also spur entrepreneurship. We all gain.

Asphalt and concrete are necessary – but not sufficient. They need to be matched by ‘soft’ aspects such as social cohesion and social safety nets. So that no one gets left behind, or feeling too bitter…

Only by investing in collective human security can we hope to boost our personal security. This is not new idea; implementing it doesn’t need to burden the overstretched state either.

For example, Sri Lanka’s largest development organisation, the Sarvodaya Shramadana movement, has long advocated and practised a balanced approach to economic development. In thousands of villages across the island, they have engaged people to live by a slogan: “We build the road — and the road builds us!”

In its haste to rebuild and grow fast, is post-war Lanka forgetting these and other proven strategies? Can we afford to race ahead leaving many citizens to fend for themselves? What happens when pent-up anger and frustrations spill over or blow up?

I’m not suggesting a simplistic link between these macro trends and the private tragedy that snuffed out Mel’s life. But none of us can claim to be innocent victims.

In Tunisian wisdom, at least, we all share the responsibility for things that go wrong – and the obligation to put things right again.

This isn’t a call to charity, but an invocation of enlightened self interest. No one is immune or fully shielded from crime, pollution, disasters and epidemics.

In another century on the other side of the planet, pondering the imminent outbreak of the biggest of all wars, an Anglo-American poet wrote an evocative verse titled ‘September 1, 1939‘. It belied the helplessness of an individual against the forces of ultra-nationalism and tyranny.

I keep returning to Auden, who has captured our imperative so aptly:

“There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police;

We must love one another or die.”

[In fond memory of Mel Gunasekera (1973-2014): friend and journalist, a fellow traveller who cared.]