[Parakramabahu (1153-1186) holds the yoke of sovereignty which has only been upheld since by military power and force, rather than by the consent of the people]

[Today, the easy co-existence of opposites symbolized by the ballot and bullet walking together]

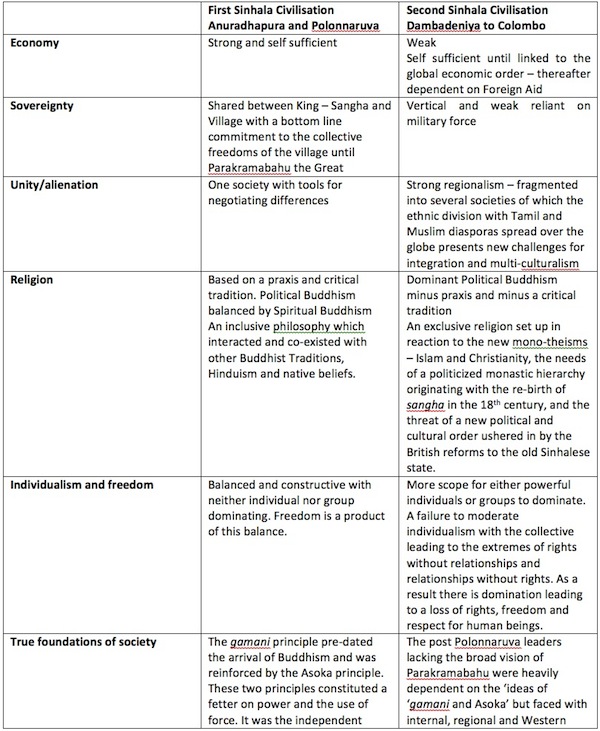

The intellectual gaps that reinforce our intellectual poverty appear readily as we scrutinize the grand shift from a united and self-sufficient irrigation civilisation to an increasingly fragmented, defensive and dependent civilisation that began in the 13th century. Although this shift is symbolized by the phrase drift to the South West stability has eluded us and we continue to search for organizing principles, unifying reference points and order. In fact chronic long term instability has been the order of the Lankan nation for centuries.

Liyanagamage, while providing a valuable analysis of the Decline of Polonnaruva and Rise of Dambadeniya continues to stick to the grand theme of our historians, the story how unity and integrity was maintained by the kings, nobles, sangha and people acting in concert. The paradigmatic structural changes that came about with the loss of the centralized state to reiterate separation, difference and inequality within the Lankan polity are of less concern as we continue to emphasize these traditional positives.

However from our vantage point in 2011 we have seen the rapid dissolution of the State immediately after the work of Parakramabahu the Great in Polonnaruva and Parakramabahu VI of Kotte due to the absence of strong supporting fundamentals. The same can be said of the present State in that the British imposed a unified administration which has since then struggled to achieve a degree of political cohesion, peace and stability.

The flaw that seems to have dogged our history and historians is the uncritical continuation of the pre-Polonnaruva grand theme of unity into the post-Polonnaruva era thereby ignoring the underlying narrative of alienation.

Two historians who have taken a more independent stance are Martin Wickramasinghe and PB Rambukwelle. Their insights on the transformation of the Lankan polity from a state of shared sovereignty to vertical sovereignty, the weakening of the self sufficient village, the alienation of the elite from the people through the adoption of Sanskrit, Pali and Brahmin customs, regionalism and ascendancy of the govikula and an enduring need to maintain primordial racial, religious and caste based identities notwithstanding educational and economic empowerment give clear directions for future research. Such studies are essential to build an intellectual platform for a modern Sri Lanka that is able to negotiate both the grand theme of unity and the underlying narrative of alienation with equal sensitivity.

What we see today is a revival of this grand theme (capitalizing on the military success over the LTTE) to obliterate the underlying narrative. It is the responsibility of the intelligentsia to bring out unbiased historical data to point out how our society became split and divided into so many camps and how these divisions originated in history. We cannot continue to ignore and neglect the important second phase of our history post-Polonnaruva and pretend with child like innocence that the journey from Vijaya down to 2011 is one unbroken theme of unity against adversity.

The discontinuities after 1236 (the year that the second Dambadeniya King Parakramabahu II was enthroned) are so paradigmatic that there is a strong case to argue for the separate historical treatment of what we may refer to as the Second Sinhala Civilisation that grew around the drift to the South West in search of security and stability. We are direct heirs to this weakened Second Civilisation. The capitals were moved to cities of which only Kotte succeeded for 50 years in the 15th century to assume sovereignty over the entire island. Regionalism was more significant than centralized power. Ultimately it was Colombo, the capital of international commerce, a capital that no Sinhalese King could capture, that became the centre of a post British settlement, what we can refer to as the Colombo Consensus of liberal politics from 1931-71.

In the first phase of this DRIFT we moved from Dambadeniya to Yapahuwa to Kurunegala to Gampola to Raigama and then finally to Kotte. The stronghold of the Sinhalese was no longer Ruhuna or Dakkhinadesa developed by Parakramabahu the Great but the mountain fastness of Kanda Uda Rata, and it is to this that we turned after the protracted struggles against the Portugese ended up with the dissolution of both Kotte and Sitawaka.

The period of roughly 350 years from 1236 to 1594 (the crowning of Konappu Bandara as Vimaladharmasuriya I represents the first unstable phase of this Second Civilisation whilst the period of roughly 200 years from 1594 to 1815 represents the final consolidation of an insulated Sinhalese culture, religion and identity against a world which had now overtaken us by leaps and bounds. What we have today as Sinhalese and Buddhists is mostly what was salvaged in that period and we must decide what aspects of that legacy should be excised if we are to ever justify any relationship with the First Sinhala Civilisation.

In the tortuous journey from Polonnaruva to the relative safety of Kanda Uda Rata Jayawardanapura Kotte provided a brief respite of about 150 years. It is a matter for reflection that the ‘capitals’ since Polonnaruva were actually defensive forts purpose built for military purposes.

Kotte was born out of a need to re-establish control over the south western coastal belt from the tax collectors of the King of Jaffna who had become bold as to send them right into the Sinhalese heartland of Dakkhinadesa. With the King cloistered in Gampola his Chief Minister Nissanka Alagakonnara was equal to the task and he defeated the forces of Jaffna decisively and named the new fort, protected by marshes as Jayawardanapura. The name probably fitted for the long reign of Parakramabahu VI from 1411-1466 but with his death Jaffna revived once more and the Sinhalese were back in the familiar plight of disputed royal successions, regional politics and disunity. Whilst Kotte served the object of local domination as a royal capital to some extent it failed to survive in the new era of international politics with the Portugese breathing down its neck. Jayawardanapura turned out to be a misnomer with Kotte losing control of the Maritime Provinces and its last King Dharmapala (yet another misnomer) gifting the Kingdom to the King of Portugal. Sitawaka Rajasinha delivered the coup de grace by flattening the remains of Kotte using an army of elephants.

Perhaps the origins of our present political culture could be found in the character of our rulers in the last two Kingdoms of Kotte and Kandy. Our policies based on power rather than ideals were probably fine tuned within an increasingly unequal relationship with the Western Powers – Portugese, Dutch and British. As Alan Strathern remarked about the Portugese Period in his book Kingship and Conversion in 16th Century Sri Lanka (Cambridge 2010)

The whole system of political relationships was imbued with a more profound sense of contractualism. The ties of vassalage required constant attention and re-negotiation.

The dominant style of kingship was sena or the warrior mode exemplified by Mayadunne, Sitawaka Rajasinha, Wimaladharmasuriya I and Rajasinha II. This pattern has been revived with General Fonseka emerging as the opposition candidate at the 2010 Presidential Elections and ‘Ranaviru’ candidates coming forward to Local Government Elections. The appeal to military authority and discipline comes at a time of breakdown of law and order and a decline in the authority of the Police and civil administration. It is however important to appreciate that both military and civil authorities have their appropriate spheres of competence and operation. The idea that one can replace another is a dangerous fallacy.

The contributions of the British, both positive and negative must be evaluated against this drift and decline and not against the First Sinhala Civilisation we had left behind forever as we moved into the power politics of international trade, domination and exploitation. The principal fault line of the British lay in the haste with which they dismantled the old social system and established a modern political and judicial system and economy. The Lankans cut off from their old social norms were adrift in unchartered waters. They opted to be Englishmen in society and natives at home and in their temples. This separation came naturally to a people who had already laid the foundations of tokenism and lip service to Buddhist values within their own religious structure. Values would be preached but they would not be allowed to obstruct the new pursuit of self promotion and self advancement.

The challenge of modernity for the Second Sinhala Civilisation

Residual Authenticity

There are three authentic Constitutional principles that bound our ancient society which can still be pressed into service despite the ravages of time. These are the fundamental checks and balances that operated to moderate the exercise of ancient sovereignty between village, sangha and king. They are,

- Gamani principle of the free and self sufficient community

- Asoka principle of righteous kingship

- Nalanda principle of honest and righteous collaboration

The people of this country have been and will always be the ultimate arbiters of these principles. From Dutugemunu to Parakramabahu these foundations shifted as time itself worked changes within ancient society. Ultimately what the people gave freely to Dutugemunu was taken by force by Parakramabahu.

The Second Civilisation that was founded by the Sinhala Vanni Chiefs Vijayabahu III and his son Parakramabahu II was therefore based on a lesser and relative freedom. Military force or sena became an indispensable fourth element of Sinhalese sovereignty reflecting the new state of collective insecurity. It created a survival oriented society that valued conformity above individualism or individual freedom. This society was dominated by a new Political Elite who subscribed nominally to the values of the First Civilization but institutionalized an ethic of dualism and separation, making a radical departure from our Axial Age heritage of transcendental humanism. It also drew a sharper distinction between mainstream society and the marginalized lower strata outside the govikula. Both then and now, the defection of these segments to Christianity is an irreconcilable thorn in the flesh among the majority Buddhists. Realpolitik in this Post Polonnaruva age would depend less on values and more on superior force and the force of superior ideas. But these ideas would only be a cover for the power of money.

It is only left to the people again to recover what they lost.