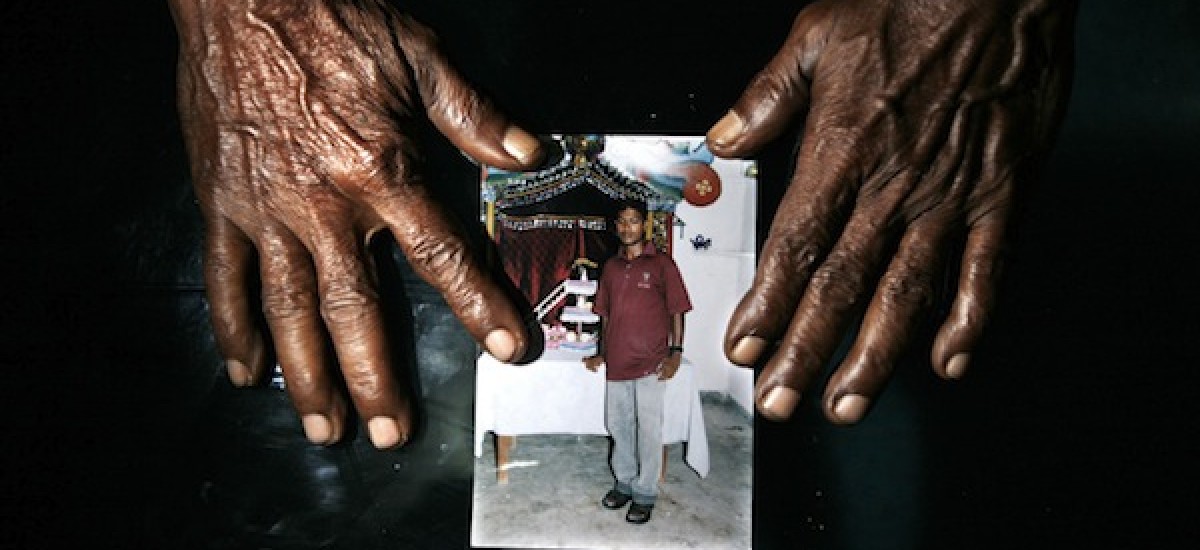

Photo from HRW

A speech made today at a Vigil to Remember the Disappeared in Sri Lanka on The International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances, held from 5-6pm at the State Library of Victoria premises in Melbourne, Australia.

I am honoured to have been asked to speak at this Vigil, to Remember the Disappeared in Sri Lanka on this important occasion, of The International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances.

Sri Lanka is party to diverse declarations and conventions of the United Nations on human rights. Therefore, the main responsibility of protecting peoples’ rights lies with the government of the day.

Today’s vigil calls upon the government of Sri Lanka to release the names of those individuals, who surrendered to the government forces during the last phase of the armed conflict in 2009. This Vigil also demands the government of Sri Lanka to put an end to the practice of enforced disappearances.

These disappearances can be categorised into those enforced in the north east of the country, during the armed conflict between the LTTE and the government forces; and in the south in 1971, and again in the 1989-1990 period, during the insurrections between the Sinhala youth and the government forces.

There had been kidnappings and disappearances that had occurred in 1971 in the south of Sri Lanka. From 1988 onwards, there was a marked increase in the number of reported detentions or abductions and killings carried out by groups of armed men wearing civilian clothes.

Even now, if somebody were to ask how many people disappeared between the years 1989 and 1990, nobody would really know. The level to which the whole cycle of killing had degenerated was such, that no one was safe, young or old. The security forces openly advocated a policy of killing ten people living in a particular area, for each security personnel killed in its vicinity.

According to the Amnesty International, in 1989 alone, more than 3,000 people were initially reported to have disappeared in the south; but the true figure is believed to have been substantially higher.

They frequently abducted victims from their homes at night, without indicating the basis of detention, or where the person was being taken to. When relatives inquired at police stations or army camps, the officers denied any knowledge of the victims; they had simply disappeared.

Many people taken in this way are believed to have been killed. Others were found in custody, or had been released after periods of unacknowledged detention.

Their cases provided direct evidence, of the involvement of security forces in these operations. In some cases, witnesses have recognized the abductors.

There have been many cases of disappearances of well-known people like Mr Sathyapala Wannigama, a young university lecturer at the time of his arrest.

In 1989, he was one of the first people to disappear in the south, and had been abducted by four police officers including two from the Special Task Force (STF). Since then, two habeas corpus applications had been filed in an attempt to locate him, but without result. The police denied that he was arrested.

To better understand what happened in Sri Lanka between 2005 and 2009, I will tell you a story that attracted wide public attention in the year 1990.

It is about a well-known Sri Lankan journalist, broadcaster and actor, late Mr Richard de Soysa. On 18 February 1990, six armed men arrived at his Colombo home. A couple were in police uniform; the others were dressed in black.

When Richard de Soysa’s mother, Dr Manohari Saravanamuttu, asked to see their identity cards, they threatened to kill her. They stormed into the house, and took Richard de Soysa from his bed.

He was abducted in the open, and the abductors were well known. In Richard’s mother’s words:

‘They were not masked… They didn’t try to hide themselves from anybody; they went in the night, asking the way to our house. …They came with a purpose, they came as killers. …They stood under the lamp, and all the neighbours saw the man who stood under the lamp.’

This man under the lamp was a Senior Superintendent of Police. Richard’s mother made a police complaint and the investigation was, of course, spurious.

Richard’s naked body was found the next day in the sea, off Moratuwa beach. A post-mortem examination found that Richard had been shot twice, through the neck and head at close range. The magisterial inquiry that commenced from then onwards, made the people understand what was going on, behind the façade of democracy and Buddhism used by the ruling elite.

During this period, several lawyers had been killed just because they continued to represent the interests of the abducted. Witnesses who testified at inquiries had also been threatened and killed, apparently to prevent them from testifying in court.

The great majority of the disappeared were young men from poor rural communities. Buddhist monks were also among the disappeared, as were people arrested as substitutes for a wanted relative.

Given those horrors, one would think that the situation would have improved since then.

Not according to the recently issued Annual Report of the International Committee of Red Cross (ICRC). According to this report, as at 31 December 2011, the ICRC has been trying to trace 15,780 people in Sri Lanka including 1,494 children and 754 women. Only a paltry 136 people have been traced to their families. According to the President of the Red Cross:

‘Thousands remained unaccounted for, leaving relatives without definitive information about their fate.’

In the history of Sri Lanka, including in the recent past, the state and successive governments have provided impunity to human rights violators.

In addition to the discriminatory policies and practices implemented, horrible crimes have been committed against the Tamil people during the final stage of the war. Many disappearances have taken place during this period.

As the Red Cross Annual Report indicates, in Sri Lanka, disappearances have escalated during this century. In the south of the country, state’s suppression of political dissent continues. Journalists and media workers have been murdered or forced into exile; lawyers and judges are been threatened.

I was in Sri Lanka during the Presidential Elections held in 2010. The journalist Prageeth Ekneligoda met me the day before I left Sri Lanka. He was working for Lanka E-News, an electronic news web site, which had already been subject to government intimidation. The next day, he was reported to have been abducted, with his whereabouts not known since then.

The former attorney general and some government ministers have concocted several stories to cover up this, and mislead the Human Rights Council of the UN and the people of Sri Lanka.

A state does not have the right to decide and define the limits of fundamental freedoms and human rights of its citizens. On the contrary, a state is obliged to safeguard the rights of every single citizen to the maximum, especially during the times of war. Unfortunately, our experience proves otherwise.

Some seem to believe that a change of constitution on paper will address this issue. No, it will definitely not. The power bestowed upon the executive has reached unprecedented levels with the 18th amendment to the constitution made last year. The executive can decide who should head the judiciary and any other public commission.

When the wife of Prageeth Ekneligoda went to the Human Rights Commission in Sri Lanka to make a complaint about the disappearance, it was not even accepted initially.

Lalith Kumar Weeraraju and Kuhan Maruganandan, both activists of the Movement for Peoples Struggle, were abducted in Jaffna on 9th December 2011. Previously, they had been unlawfully arrested and detained for campaigning against abductions and the political prisoners detained in camps without being charged. When the Human Rights Commission was notified that they were being held in a building in Colombo, the Commission simply refused to search the premises.

Even three years after the war, many people in the south, are not willing even to consider, that abducting Tamils, torturing them in detention or making them disappear as serious crimes. People in the northeast were silent when people in the south were subjected to torture and disappearances. People in the south supported the state when people in the north and east were subjected to torture and disappearances. This has made it easier for the government, not only to keep the people in the north and east repressed, but also to suppress any political dissent in the South.

Time has come, for all people in Sri Lanka and elsewhere, to unite and demand an end to all forms of torture and disappearances.

The protection of human rights requires action, not words. Ensuring that those responsible for torture and disappearances are brought to justice, and held accountable for human rights violations, will convey the clear message, that such rights violations will not be permitted to continue.

The international community has a clear responsibility to ensure this. We need a renewed and forceful commitment by individuals, journalists, professionals, trade unions, human rights groups and, above all, by governments such as Australia, to expose and denounce torture and disappearance whenever and wherever they take place.

The sooner the better it would be for us all.

Thank you for your kind attention.