Much of Sri Lanka’s Dry Zone is currently grappling with a drought caused by the delayed Monsoon. This is a double whammy for residents in several districts who have been engulfed by another ‘slow emergency’ for two decades: mass scale kidney failure affecting large numbers.

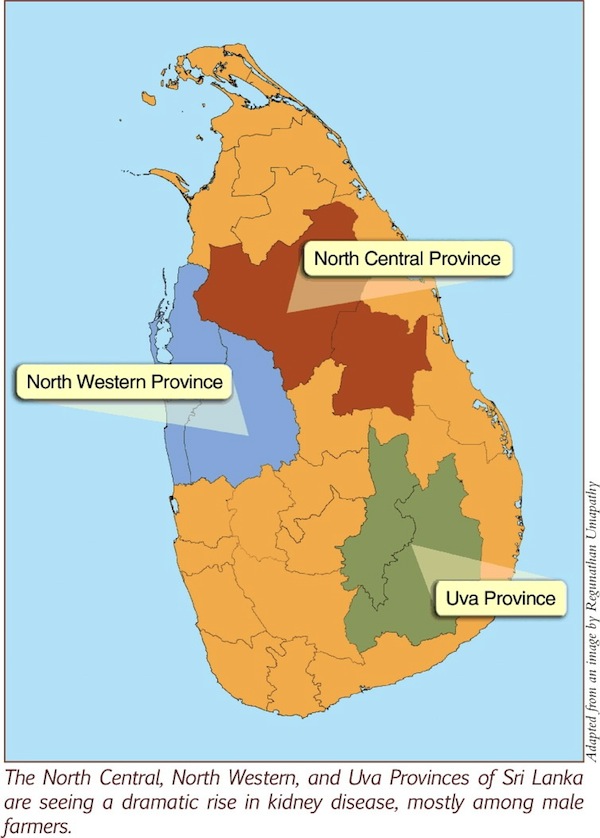

Diabetes or high blood pressure can lead to kidney failure. But beginning in the 1990s, thousands of people in the North Central Province (NCP) developed the condition without having either factor. Most were male farmers.

This puzzled doctors and other researchers who struggled to understand how and why. It was soon assigned an official name: Chronic Kidney Disease of unknown etiology (abbreviated as CKDu).

CKDu has evolved into a humanitarian tragedy on a mass scale. It is claiming more victims every passing year, spreading to more areas, and gradually overwhelming the healthcare system. Its causes are still unclear and hotly debated.

Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa Districts are ‘Ground Zero’ of this mysterious ailment for which there is no known cure. In fact, it was first detected in the early 1990s by Dr Tilak Abeyeskera, Consultant Nephrologist attached at the Anuradhapura general hospital.

It has since spread to North Western, Uva, Eastern, Central and Northern provinces as well. The affected areas are now spread across approximately 17,000 sq km (a quarter of the island), which is home to around 2.5 million people.

Several thousand have already died; the exact number is not clear due to gaps in statistics and incomplete reporting. Hospital records show that over 15,000 people are kept alive with regular kidney dialysis.

Those who develop CKDu are mostly men between 30 and 60 years, working as paddy farmers or farm labourers. These factors are being investigated by health officials and many scientists searching for ways to contain and treat the ailment.

The latest attempt to make sense of the deepening mystery is by India’s Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), an independent research and advocacy organisation. They collaborated with the Ministry of Water Supply and Drainage, and the non-profit Centre for Environmental Justice (CEJ) in Colombo.

CSE’s scientists tested samples of drinking water, soil, rice plant and grain, pesticides and chemical fertilizer from many locations. Their study report, released in Anuradhapura on 16 August 2012, does not pinpoint one definitive factor or solve the jigsaw completely. Yet it clarifies some issues and takes the debate forward.

What causes it?

Helpfully, the CSE report collated many theories and speculations on possible or probable causes of CKDu.

Listed in no particular order, these include: excessive cadmium in the natural environment; high levels of fluoride in drinking water; using fluoride-rich water in low quality aluminium pots; “hard water” with higher than normal levels of minerals; and toxins generated by blue-green bacteria in the water.

Humans are exposed to multiple elements over time. Finding one rogue element is never easy. So factors such as illicit liquor and Ayurvedic medicine are also being studied. Meanwhile, a team at Peradeniya University is probing whether people in affected areas have a genetic predisposition.

In 2011, some researchers from Kelaniya and Rajarata universities argued that arsenic in pesticides and chemical fertilizers, when combined with calcium in hard water, causes CKDu. Their findings became controversial when one researcher claimed to have derived key insights through ‘divine intervention’.

So is it Nature, nurture, or a combination of the two, causes this misery? Nobody knows – as yet.

Interestingly, all the areas with high incidence of CKDu are located around reservoirs of the irrigation systems. In contrast, those communities who draw their drinking water from natural springs have few kidney failures among them. Is it something in the irrigated water – and if so, what?

Planet Earth is capable of springing some nasty surprises on us, even without any human provocation. As earth scientists remind us, this is an inevitable part of living on a restless planet.

In 2009, the World Health Organisation (WHO, a specialised agency of the UN system) and the Health Ministry’s epidemiological unit appointed 10 study groups to study this problem. Their findings have been submitted to the government but not yet released. Why?

We cannot afford bureaucratic apathy in a matter of such urgency and importance. The outcome of public science must be shared with the public and media in the public interest.

Beware of opportunists!

Delays in releasing research and analysis will only allow speculation and conspiracy theories to gain momentum. Selfish opportunists are already flocking to CKDu hit areas apparently seeking to implicate their pet hates. Sadly, some of these speculations are being peddled – and even cheered — by sections of our media without due diligence.

Such tilting at windmills is muddying the already suspect waters and can confuse policy makers. Senior scientists like Prof Oliver Ileperuma and Prof C B Dissanayake – at the forefront in related research — have stressed the need to separate facts from speculation and myths.

Another fervent plea for sanity appeared recently in the respected Ceylon Medical Journal (CMJ). Established in 1887, CMJ is published by the Sri Lanka Medical Association (SLMA), the national professional body of doctors. Writing in the December 2011 issue, three medical researchers — A R Wickremasinghe, R J Peiris-John and K P Wanigasuriya – called for dispassionate discussion of current knowledge and gaps.

Given the widespread discussion and debate in the media recently, they urged, “it is timely that the available, credible, scientific evidence on CKDu (published in peer reviewed journals) is collated and analysed, and the difficulties faced in establishing causality are discussed.” (Emphasis mine)

The authors added: “The cause of CKDu is likely to be multifactorial. At this point in time there is insufficient evidence to pinpoint a cause(s). Both the wellbeing of residents of the NCP and the enormous drain on health system resources and the economy demand that resolving the issue is a national priority.”

Medical doctors are on the frontline in treating affected people and counselling devastated families. But CKDu is much more than a mere medical or health emergency. Interdisciplinary studies are needed – involving both natural and social scientists – and with adequate coverage, intensity and scientific rigour.

Miracles and Sacred Cows

Scientific credibility requires that such studies are peer reviewed and published in national and international journals of high standing. Making unfounded claims at press conferences and throwing wild allegations in TV talk shows might create some ripples, but such grandstanding doesn’t help anyone.

The National Science Foundation (NSF), our main research funder and agenda setter, can provide directions. We also need NSF to ensure the findings are widely discussed in policy, professional and public forums. Secrecy is not an option.

There is no room for miracles or absolute truths in science. By its very definition, science is open to rigorous scrutiny, challenge and refinement. CKDu is no exception.

Last year’s ‘divine revelation’ story reminded me of a famous creation by Sidney Harris, the doyen of science cartoonists. Science demands its practitioners to be more explicit and accountable than resort to ‘miracles’. No one can claim to be a sacred cow.

There are also no shortcuts in science; the scientific method cannot be circumvented or accelerated at some officials’ whim or fancy. However, urgent societal problems like CKDu warrant fast-tracked study and action. These need more funds and brains.

But remember: haste makes waste. The CMJ paper called for vigilance that mere associations “should not be considered to be of causal importance without documented evidence of proof”.

The CMJ authors hit the nail on its head when they wrote: “We advocate caution by the scientific community and the media when using such assertions that impact on policy, the livelihoods of the farming community and the economy of the country without scientific validity and biological plausibility.”

Media’s Challenge

Science and media are inherently contested public spaces. They thrive only with open, informed and inclusive debate.

We in the media face many challenges in covering this complex and nuanced story. CKDu has all the elements that typically interest the media: rising death toll, widespread human suffering, as yet unclear origins and causes, scientific arguments, and — since of late – some conspiracy theories.

During its early years, CKDu was under-reported by our urban-centred media. Well, no longer. We now face the real danger of some media outlets engaging in fleeting, superficial and alarmist reporting.

CKDu is not a straightforward or simple story to report. It’s not like a tsunami or flood. It’s even slower than a drought (a gradual disaster that many journalists struggle to grasp), and not an infectious disease.

The impact is on human beings but no visible changes in the landscape.

CEJ’s Executive Director and chief scientist Hemantha Withanage has been travelling in CKDu affected areas, meeting hundreds of families and community workers. In some areas, every third house has lost at least one family member. Survivors are migrating to cities.

He relates the eerie and heart-wrenching scenario that repeats in thousands of households where men are living from one dialysis session to another, ideally every four days. Each session costs around LKR 12,000 (USD 92 approx) to the healthcare system, and many hospitals don’t have enough dialysis machines.

Secretary to the Ministry of Health told a media seminar in early 2011 that LKR 350 million (approx. USD 2.6 million) — 4.6% of the health budget – is spent every year on supporting CKDu patients.

With thousands affected, it is only natural for emotions like despair, suspicion and anger run high. Scientists and health officials need to be sensitive to such sentiments, without allowing scare-mongers and villain-hunters to hijack policies or research agendas.

CKDu is as much a national health emergency as dengue epidemic in our cities. To find relief for those already affected and protect millions more at risk, we must harness our nation’s brain power – giving them clear focus, adequate resources and academic freedom.

Never forget, however, that this isn’t just a research problem. Fellow human beings – not lab rats – are involved. They need interim help while long term solutions are being worked out.

Both CEJ and CSE have called for better medical facilities as well as clean drinking water to reduce people’s dependence on poor quality groundwater. These are development needs in their own right.

While scientists probe causes and solutions in earnest, the government and voluntary organisations can immediately start providing relief and livelihood support to those living with CKDu.

Finger-pointing, document-leaking and conspiracy-spinning might generate cheap thrills or media coverage for some with their own agendas. But these theatricals don’t help anyone hit by, or dealing with, the formidable problem.

Let’s not allow tragedy to be turned into farce. There are indeed better ways to care for the traumatised farmers and their families.

###

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene asks more questions than he can answer, and writes weekly columns in Ravaya and Ceylon Today newspapers. All views are his own. A shorter version of this essay appeared in Ceylon Today of 19 August 2012. He blogs at http://nalakagunawardene.com.