Assorted charlatans and religious zealots across the island of Sri Lanka must have heaved a collective sigh of relief when they heard that Dharmapala Senaratne was no more. He had made it his business to make life difficult for those preying on the gullible public.

Rationalist and myth-buster Dharmapala made his final exist a few days before 2012 dawned. At 67, he still had a few more years of the good struggle left in him. He would surely have enjoyed countering the false prophets of doom — and their credulous followers — who predict the end of the world on 21 December 2012.

Although Dharmapala was also a teacher and lawyer with decades of experience, he was best known for his public activism as a rationalist. His was a determined and sceptical voice questioning fanatical peddlers of all kinds of dogmas, faiths and (mutually exclusive) brands of ‘salvation’.

Even more importantly, he fearlessly took on confidence tricksters hoodwinking superstitious people with black magic and cheap conjuring tricks. He was a courageous public intellectual in a land woefully short of their kind.

At its core, rationalism involves nurturing the spirit of enquiry and critical thinking in every aspect of life and living, at both private and public levels. In short, rationalists and sacred cows are mutually exclusive.

Dharmapala was President of the Sri Lanka Rationalist Association (SLRA), a small group of earnestly sceptical enquirers who won’t take anyone’s word about anything. They want to investigate and debate.

The voluntary group was originally set up in 1960 by the late Dr Abraham Thomas Kovoor (1898 – 1978), a Kerala-born science teacher who settled down in newly independent Ceylon and, after his retirement in 1959, took to investigating so-called supernatural phenomena and paranormal practices. He found adequate physical or psychological explanations for almost all of them. In that process, he exposed many so-called ‘god men’ and black magicians who thrive on people’s misery and superstitions.

In 1963, Kovoor issued an open challenge (with the then princely sum of LKR 100,000 tagged to it) for anyone who could demonstrate supernatural or miraculous powers under fool-proof and fraud-proof conditions. He also challenged the high profile Sathya Sai Baba of India, arguing that the latter’s ‘materialising’ of holy ash (vibuthi) out of thin air was nothing more than a sleight of hand. Kovoor’s challenges were consistently dodged by Sai Baba – and all others of his ilk.

Kovoor was fond of saying: “He who does not allow his miracles to be investigated is a crook; he who does not have the courage to investigate a miracle is gullible; and he who is prepared to believe without verification is a fool.”

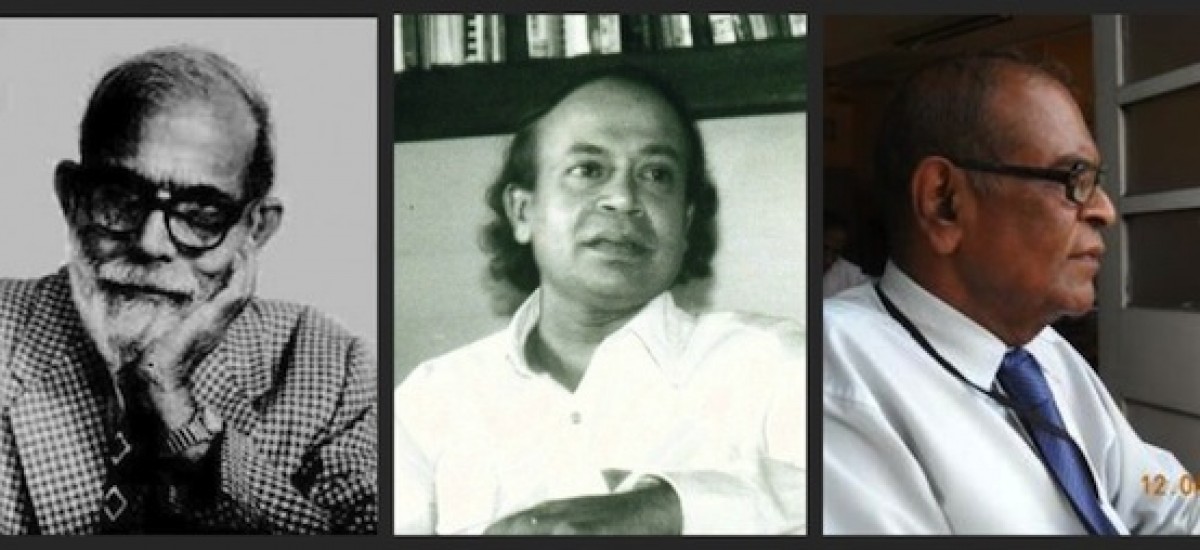

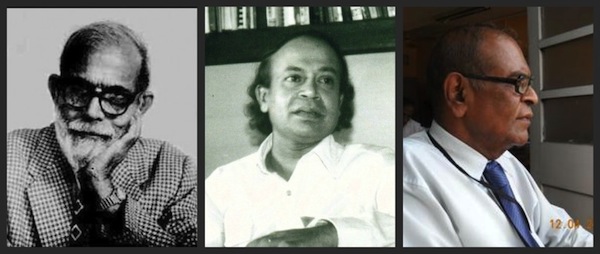

These words, and the far-reaching influence of other well known rationalists like Bertrand Russell, inspired young Dharmapala Senaratne to promote rationalism in his spare time. Two other young men who joined Kovoor in the heyday of the Ceylon Rationalist Association: Amunugoda Thilakaratne and Ajith Thilakasena, both of who became writers of their own merit. Pooling their talents, the trio popularised Kovoor’s thinking and work among the Sinhala reading public.

Sri Lanka’s rationalist movement lost its lustre after Kovoor’s death in 1978, even though (lawyer and poet) Mervyn Casie Chetty kept it going for some more years. When the sceptical flames were reignited in the new millennium, Dharmapala became its new President by popular choice.

“Dharmapala was the bridge between generations when we set out to revive the rationalist movement of Sri Lanka in 2005,” recalls Tharaka Warapitiya, general secretary of SLRA. “He helped enormously to connect us with activists who had been heavily involved in its work during the Kovoor era.”

Different Times

By this time, however, the island of Lanka had been completely transformed. The Children of 1977 – products of economic liberalisation and Sri Lanka’s first television generation – had come of age.

Partly reflecting this new reality, Dharmapala’s style was different. While Kovoor had been charismatic and flamboyant, Dharmapala was measured and studious — yet no less passionate when it came to separating the wheat from the chaff.

He was astute enough to realise that the public moods and media attitudes had changed drastically from the more conducive 1960s and 1970s.

That was when a recent Indian immigrant (well, aren’t we all that, historically speaking?) could speak truth to power and command a sizeable audience of discerning Lankans as well as attract sufficient attention of the island’s media.

That was also a time when an eager young medical graduate (Dr Carlo Fonseka) could debunk the much-hyped ‘spiritual base’ for the ‘holy’ practice of fire walking. His finding – that ‘it’s the thickness of the sole and not the soul’ that matters in walking over red hot coal – shattered a core myth that propped up sacred cows of Kataragama.

While such acts elicited predictable resistance and threats from those afflicted, societal support at the time was more open and forthcoming. Many intellectuals and newspaper editors accommodated Kovoor, Fonseka and fellow sceptics, with a gleeful Arthur C Clarke cheering from the sidelines (he would later feature them in his global TV series).

It was the song — not the singer — that mattered then. Alas, not now.

Paradoxically, we now have far more communication channels and technologies yet decidedly fewer opportunities and platforms for dispassionate public debate. Today’s Lankan society welcomes and blindly follows an entirely different kind of Malayalis who claim to know more about our personal pasts and futures than we’d ever know ourselves. And when we see how our political and business elite patronise Sai Baba, Sri Chinmoy and other gurus so uncritically, we must wonder if there is intelligent life in Colombo…

Sacred cows, it seems, have multiplied faster than humans in the past half century. Our cacophonous airwaves and multi-colour Sunday newspapers are bustling with an embarrassment of choice for salvation, wealth, matrimony, retribution and various other ‘quick fixes’ for this life and (imagined) next ones.

Embarrassment, indeed!

So Dharmapala had to adopt different strategies to reach the same goals.

He was well versed in scientific thinking and principles, to which he added his own legal perspectives.

His position was unequivocal: “Let anyone believe in anything privately if they choose to — but no one has the right to mislead others or to hoodwink them into parting with money. That’s fraud, which is against the law!”

As he repeatedly pointed out, Sri Lanka has strict laws dealing with fraud. If anyone has been tricked into paying money on false promises, the affected may take civil or criminal legal action.

In reality, however, very few do so – lest it exposes their own gullibility! Apparently, when it comes to the occult and paranormal, many ignore the time-tested caution of “Caveat emptor” (Latin for ‘Let the buyer beware’).

“This is the very weakness that fraudsters exploit,” Dharmapala said. “These are organised rackets to rob people of their hard-earned money.”

Confronting conmen

Dharmapala took on the assorted charlatans by publicly exposing their conjuring tricks and bogus claims. He also used the media (especially television, not available during Kovoor’s time) to counter the mesmerising hype peddled by the other side.

A memorable example was when, in 2010, he pooh-poohed the hilarious practice of a ‘possessed’ wooden stool (kanappuwa) ‘walking’ down the streets in search of thieves.

“Inanimate objects are completely incapable of self-propelled motion,” he argued citing the laws of physics. “These furniture items are being manipulated by the humans involved. Kanappuwas most definitely can’t catch any thieves, or the police would employ them for their own crime investigations!”

On prime time TV, he offered LKR 100,000 for anyone who could prove beyond any doubt that a stool could ‘walk on its own’. He added: “This is a complete rip-off – further victimising persons who have already lost their belongings. It’s cruel to exploit such misery!”

He also cautioned against community divisions and hatred nurtured by dubious practices like walking stools and light-readings (anjanam): those falsely implicated are immediately (and unfairly) maligned by neighbours.

As an antidote, he called for more scientific thinking and attitude at all levels of society. “If we can get our people to think more logically and critically, we can easily dispel many myths and superstitions.”

But that is just not happening enough in Twenty First Century Lanka: a majority among its 20 million believe in a broad range of superstitions, some more harmful than others. Confronting conmen can be hazardous in a post-war society where trigger-happy goons are available for cheap.

Dharmapala reserved his most scathing criticism for (apparently) educated Lankans dabbling in unproven or fraudulent practices. This includes a number of credentialed scientists trained in disciplines such as astrophysics, geology, atmospheric physics or nuclear chemistry.

“Tragically, certain individuals with legitimate Ph Ds in various branches of science also engage in peddling pseudo-science and bogus practices. Some are doing it with commercial motives. Others, for cheap popularity,” Dharmapala said.

As we saw during the 2011 controversy over arsenic in rice, some of these learned men and women won’t allow hard evidence get in the way of a good conspiracy theory! And large sections of our media (especially in Sinhala) hero-worship them uncritically, labelling them as ‘patriots’ and projecting them as ‘defenders of indigenous knowledge’.

Dharmapala entered many contentious debates when a majority of our intellectuals diligently avoided them. He didn’t mince words when taking on scientists indulging in pseudo-science or complete non-science. He wrote in one such debate on hypnotism as ‘proof’ of reincarnation: “When learned people like Dr. J propagate and disseminate misconceptions, ordinary folk tend to be misled and embrace wrong notions thereby rendering their thinking faculties blunt.”

Rational communicator

Frustrated by the limitations of our uncritical mainstream media, he also communicated through books and the new media, so that discerning readers can make up their own minds.

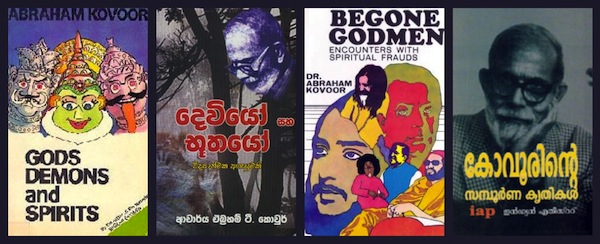

His lasting contribution to rationalist literature was translating two seminal works by Kovoor: Begone Godmen, and Gods, Demons and Spirits. He also penned three original books: Kovoor saha Hethuwadi Darshanaya (Kovoor and Rationalism); Sai Baabage Anduru Paththa (The Dark Side of Sai Baba); and Elowin Aa Jeewakaya saha Wenath Hethuwadi Lipi (The Healer from Outer Space and other Rationalist Essays).

Unlike many others of his generation, Dharmapala kept up with the march of communications technologies. Early on, he recognised the web’s potential for nurturing public debate and promoting the public interest. He joined the Secular Sri Lanka group blog, well aware how its thematic focus evokes the wrath of Sinhala Buddhist nationalists. He was also active in various online discussion forums and social media platforms (such as Facebook, Twitter, All Voices and LinkedIn), and was fond of sharing interesting weblinks.

While engaging the new media, Dharmapala never gave up on the old media. He was a prolific writer of letters to the editors of English newspapers in Sri Lanka. Whatever the topic – from faith healers and vegetarianism to demons and reincarnation – he was an indefatigable practitioner of this quaint craft: he would doggedly pursue an exchange until editors intervened to close a prolonged debate.

Hopefully, these multiple communications woke up a few from their culture-conditioned and society-enforced slumber. But how do we awaken those who only pretend to be asleep?

Why do otherwise moderate people turn emotional and fiercely defensive in any discussion about their religious faith? Why is it that a majority of Lankans seem so threatened if anyone were to even mildly question the ‘certain certainties’ of a dogma randomly assigned to them at birth? How come any discussion on secularism in Sri Lanka elicit so much vitriolic comment from the virtuous defenders of a religious state?

Could it be because, as Mark Twain once remarked, “Faith is believing what you know ain’t true”?

Sure, it’s a free world: every individual may choose what to believe in, and also change beliefs from time to time. That’s fine — as long as believers confine it all to their own private lives. But when some try to force their beliefs on everyone else, or institutionalise these as state policies, it becomes hegemony.

In a heated newspaper exchange on the ultimately unverifiable existence of an afterlife, Dharmapala said December 2009: “Having been brainwashed from the very first day of birth and then throughout a lifetime, different religionists hold a deep rooted conviction in mind that only the particular dogma, taught by their respective religions, is the absolute truth and what is taught in other religions is false. Thus, while Buddhists and Hindus are absolutely certain of rebirth, Christians and Muslims are equally certain of Almighty God and Creation.”

Associates confirm that Dharmapala had worked on another Sinhala book, a critical look at reincarnation. Its posthumous publication could restore some sanity to the emotionally charged debates on this topic.

Credulous Nation?

Meanwhile, true Buddhists – may their tribe increase! – could finally start following what the Buddha taught. For half a century, Lankan rationalists have been citing, as one of their favourite quotes, the Buddha’s well known advice to the Kalamas, captured in the kalama sutra.

Kovoor used to quote this regularly at public meetings, as do his successors to this date. The Buddha’s rejection of authority, tradition, hearsay and dogma, and his position that one should accept something as true and valid only on the basis of verification by oneself, is probably one of the earliest rationalist principles expressed in history.

But as Colombo University’s historian and public intellectual Dr Nirmal Ranjith Dewasiri told a rationalists’ meeting in Colombo last week, a majority of today’s Lankan Buddhists would rather not follow that sound advice. Doing so risks shattering too many dogmas and contradictions on which their history and current political posturing are based…

It remains to be seen who among our rationalists would take up the daunting task of keeping the sceptical flame alive. Doing so now is even more critical than when Kovoor founded the movement. At stake is much more than debating religious faiths, or safeguarding the public from exploiters of ignorance and misery.

As astronomer and science populariser Carl Sagan put it so well in his last book, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark (1995): “If we can’t think for ourselves, if we’re unwilling to question authority, then we’re just putty in the hands of those in power. But if the citizens are educated and form their own opinions, then those in power work for us. In every country, we should be teaching our children the scientific method and the reasons for a Bill of Rights. With it comes a certain decency, humility and community spirit. In the demon-haunted world that we inhabit by virtue of being human, this may be all that stands between us and the enveloping darkness.”

Early in life, science writer Nalaka Gunawardene was influenced by educator and free thinker Dr E W Adikaram, and later worked with Sir Arthur C Clarke as his research assistant. He thanks Dr Kavan Ratnatunga and Tharaka Warapitiya for some information used in this essay, but the opinions are entirely his own.