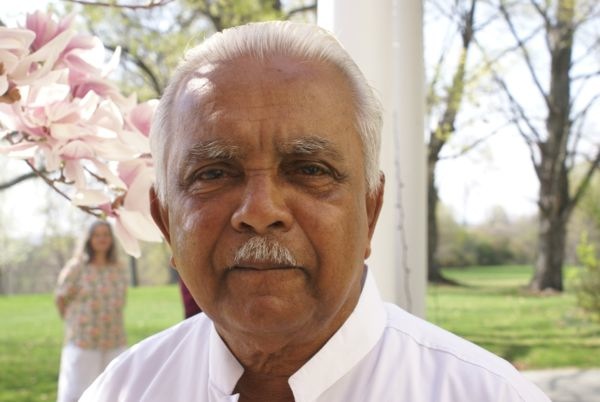

Photo courtesy Sarvodaya Media Unit

When Dr A T Ariyaratne, founder and president of the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement of Sri Lanka, turned 80 years on 5 November 2011, felicitations poured in from all over the world. This spontaneous act was an indication — if any were needed — of how much and how widely he has touched the lives of millions.

For someone with global stature, Ahangamage Tudor Ariyaratne is completely devoid of pomposity. In a career spanning six decades, he has received some three dozen awards and honours — including the ‘Asian Nobel’ Magsaysay Award (Community Leadership, 1969), honorary degrees and doctorates, and the highest national honour from his own country, SriLankabhimanya (Pride of Sri Lanka). But he remains a simple and amiable man. He is still ‘AT’ to contemporaries, ‘Ari’ to us fellow travellers, and ‘Loku Sir’ (Master) to all at Sarvodaya – the largest development organisation in Sri Lanka. The apolitical people’s movement has a presence in over 15,000 villages.

Ari is also our elder statesman of inclusive development. For over half a century, he and Sarvodaya have advocated a nuanced approach to overcoming poverty, illiteracy and various social exclusions. Unlike some die-hard activists, Ari doesn’t ask us to denounce materialism or revert to pre-industrial lifestyles. Instead, he seeks a world without extreme poverty or extreme affluence.

Suddenly, his quest for social justice and equality is resonating all over the world. In fact, Ari has been speaking out for the 99 per cent of less privileged people decades before a movement by that name emerged in the West. In a sense, those occupying Wall Street and other centres of affluence are all children of Sarvodaya.

While Ari shares their moral outrage, his own strategy has been quite different. He didn’t occupy physical spaces in his struggle; he went straight to the fount of all injustice – our minds.

Shared work, voluntary giving and sharing of resources form the bedrock of Sarvodaya’s approach to doing good, but these are not random acts of charity. They are all means to achieving the ‘awakening of everyone’ – starting from the individual and family, and going up to village, national and global levels. There is strong spiritual base to Sarvodaya, albeit a non-doctrinal one. It is inspired by Buddhism, yet not deep immersed in it.

Ari is the lead thinker of Sarvodaya. He has guided the movement from humble beginnings in 1958 to its globalised, internationally recognised level today. Luckily for everyone, Ari wasn’t just a deep thinker but also a practical and passionate activist. Early on, he struck a healthy balance between theory and practice.

Thanks to him, Sarvodaya’s vision is thoughtful without being pedantic; its work is systematic without being too bureaucratic. Sarvodaya staff and volunteers are not robotic do-gooders controlled from their headquarters: they are motivated, disciplined and resourceful (I’ve worked with many). At all levels, they know what to do, how – and more importantly, why.

In Ari, we find elements of Mahatma Gandhi (non-violent pursuit of the greater good); the Dalai Lama (interpreting Buddhist philosophy for the modern world); Martin Luther King, Jr. (struggling for the rights and dignity of marginalised people); Nelson Mandela (nurturing democracy and healing society); and Jimmy Carter (globalism with a humanitarian agenda).

Yet Ari is more than the sum of these noble parts; he is his own unique visionary. And an adroit ‘remixer’ who constantly blends the best of East and West. He adapts our civilisational heritage to tackle the Twenty First Century’s anxieties and uncertainties. Thankfully, though, he doesn’t peddle simplistic solutions to today’s complex problems.

On the Frontline

Ari is a man on the move, endlessly criss-crossing his island, leading from the front. When he turned 75, he told me that he was still averaging 100 to 150 km of inland travel every day. Come Hell or high water – he has faced plenty of both — he goes where the needs are. And he shows no sign of slowing down.

Ari has built more ‘bridges’ in Sri Lanka than all its post-independence governments. His ‘bridges’ are between people: he has connected all ethnic, religious and linguistic groups who share our island, nurturing trust and cooperation among them. As policy analyst Chanuka Wattegama says, Ari is perhaps the only leader in Sri Lanka to rally all Lankans under one umbrella — not a single politician has achieved this feat.

So how many lives has Sarvodaya saved over the decades?

The movement’s wide-ranging social development programmes have improved the lives of millions through better health, nutrition, literacy and education. Meanwhile, its humanitarian programmes have literally made the difference between life and death in times of disaster or conflict.

When the Indian Ocean Tsunami struck in December 2004, Ari and his team were the first responders, reaching some affected communities within six hours; government relief efforts took two or more days. Likewise, Sarvodaya maintained its non-partisan and humanitarian presence even during the height of hostilities between Lankan armed forces and Tamil Tigers in war-ravaged areas.

However, we must look deeper to discover Sarvodaya’s greatest accomplishment in preventive action. Consider the large number of Sarvodaya-affiliated young men and women who simply refused to join the Marxist insurrections in 1971 and 1987-89, and the separatist terror that triggered our civil war. If not for Sarvodaya’s positive engagement of youth, the death toll of our trinity of uprisings could have been far higher…

Courage of Conviction

While Ari is an avowed man of peace, he can be an indomitable defender of his movement and its principles. Faced with injustice, the genial ex-schoolmaster becomes a mighty force to reckon with. I witnessed that facet of Ari when I first interviewed him in early 1991.

For unclear reasons, President Premadasa had unleashed the full powers of the state to persecute Ari and Sarvodaya through an infamous NGO Commission. As the people’s movement was confronting a ruthless bureaucracy and opportunistic critics week after week, most of the media was too scared to carry Sarvodaya’s side of the story. My seniors at The Island were hesitant to interview the man at the centre of this storm; being idealistic and curious, I volunteered.

Ari spent an entire morning talking with me, then a cub reporter, placing everything on the record. I asked some piercing questions, all of which he answered with clarity and purpose. He systematically debunked the many allegations against Sarvodaya. He also called for a co-existence between government, private and people’s sectors: the problems of under-development and social exclusion were too enormous to be tackled individually, he argued.

Photo courtesy Sarvodaya Media Unit

Half way through the interview, I popped the question that everyone was asking: Are you politically ambitious?

“I have no ambition to hold political office,” he answered. Then he quickly added: “But I am very political – in the sense that I want power at the centre to be totally brought down to the people, so that we can enjoy our human rights – freedom of speech, freedom of expression, freedom of participation, and decision-making. Democracy to be really with the people.”

I had an explosive interview. But our editor was overseas, and no one else was willing to take responsibility. So my transcript went right up to the company’s managing director. James Lanerolle, the retired civil servant heading Upali Newspapers at the time, deemed it should be printed in full. So it appeared on one and a half broadsheet pages in The Island on 2 February 1991 with the provocative headline (not mine): “I am very political!”

Photo by Amal Samaraweera

A few months later, while the state was still bashing him mercilessly, Ari and I found ourselves departing Sri Lanka on the same flight. Concerned strangers surrounded Ari at Immigration, Customs and the flight gate, expressing their dismay at the prevailing injustice and urging him to stand his ground. Ari later told me that this had become a daily occurrence: such solidarity only steeled his resolve.

It took a dramatic — and brutal — turn of events before Ari and Sarvodaya could breathe more easily again. Ari didn’t rejoice at the assassination of his tormentor. He just picked up from where he’d left off.

Before and since, Sarvodaya-bashing has been a popular pastime for some. Its critics remind me of the Lankan fable about five blind men meeting an elephant. Each feels one part of its body and imagines – very differently – what the whole being is like. None of them gets close to the real picture.

While a few critics helped the movement to sharpen its focus, many only held up progress. Journalist Gunadasa Liyanage, who wrote Ari’s first biography (Revolution Under the Breadfruit Tree, 1987) asserted that Ari had probably spent 75 per cent of his time defending himself and the movement from unfair attacks, or repairing the damage. Just imagine…

In his time, Ari has prevailed over many naysayers, back-stabbers and oppressors. He has survived thugs and death squads, and astounded doubting Thomases. He can have the last word and last laugh — but chooses not to. Such equanimity and compassion are uncommon.

Best of Sri Lanka

Despite the occasional rough handling he received nationally, Ari has consistently promoted his country internationally. He is one of the best known Lankans in the world today, held in equally high esteem in both the East and West. In countries like Japan, India, the Netherlands and the United States, people pay and flock to hear his talks. From the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) to economies in transition (in Eastern Europe), planners are studying Sarvodaya’s development model.

It’s not just talk. Ari’s global engagement has produced some tangible results. Beginning in the mid 1960s, Ari travelled the globe addressing numerous gatherings of academics, activists, development workers and politicians. His thinking influenced development and humanitarian policies. His vision inspired thousands of well-intended young people to pursue meaningful careers in the development and voluntary sectors. He gave purpose to hapless UN officials searching for the UN Charter’s goals of peace, security and development.

Each such act accrued goodwill for his country. With no official status or state resources, Ari has also done more to project a positive image of Sri Lanka than has our entire Foreign Service combined. Unlike our diplomats who feel the need to ‘lie abroad for their country’, however, Ari just speaks truth to power. He is accommodating and open to dialogue, with none of the dogma and self-righteousness of our nationalists.

As the Sri Lankan state searches for ways to reposition itself in the world after three decades of war, it can learn a few lessons from Ari. Sarvodaya showcases the finest that Sri Lanka can offer the world intellectually, spiritually and culturally. These experiences are well documented and available for free — even to expensive spin doctors!

The movement epitomises Lankan ‘soft power’ at its best: engaging the world on our own terms, and earning global goodwill for fresh thinking, principled positions and exemplary service or performance. Also in this select group – albeit for different reasons — are the Sri Lanka Eye Donation Society and our Cricket Team. We must nurture many more.

Trouble maker?

Ari is still as open-minded, eager to learn and willing to share as I first found him two decades ago. He is a voice of reason and moderation, fearlessly speaking out on matters of national and global importance.

He is also a first class communicator. He speaks eloquently, passionately – and with malice towards none. His writing and speeches are philosophical yet eminently accessible for their simplicity and sincerity. The science teacher who followed his own conscience to work for rural upliftment and social justice has now become the conscience of a whole nation.

His mastery of modern communications technologies is impressive. He keeps up with his email. He carries around his own digital camera, and clicks liberally. He knows the power of still and moving images. He can convert cynics, disarm critics or energise thousands – all with a few carefully chosen words or images.

Oh, Ari isn’t perfect – but I find his imperfections just as endearing. He trusts people too much, and hasn’t changed that trait even after many betrayals. He can be a bit naïve in believing that mass meditation by peace-loving men and women can dissuade warring politicians or rebels.

Speaking his mind has often landed Ari in ‘trouble’, but the man refuses shut up. At 80, he still plays the role of that irrepressible little boy who had the courage to say the Emperor was naked. He speaks not just for the voiceless majority, but also for many tongue-tied intellectuals who seek refuge in conformist – and cosy — silence.

Here is a recent example. In November 2010, Ari gave an outspoken submission to the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) of Sri Lanka, set up by the President as part of the post-war healing process. Drawing on Sarvodaya’s many and varied experiences, he offered seven salient lessons for a more stable and prosperous future for all Lankans (see: http://tiny.cc/LLRC-ATA). We shall soon know if he was heard, when the Commission report is released.

Sprinkled throughout his submission are profound insights and cautions not just for the current custodians of political power, but all of us who have entrusted them with that power. Here are a few striking quotes: Governments cannot legislate the feelings of people. State should be sensitive to feelings, needs and aspirations of people in a plural society. Militarisation of the country is not the answer. Every non-Sri Lankan is not out to destabilise the country. Treat the voluntary sector with respect and understanding. Governments should never depend on corrupt people, thugs, criminals and lawless elements to come into power or remain in power.

Ari kept his best to the last: “If any government thinks that national problems could be solved by military might, bureaucratic control and media propaganda, hasty legislation, over-reliance on the Prevention of Terrorism Act and such other legislation, it is committing a grave mistake which will reverberate on the government later.”

No wonder his submission didn’t get much media coverage in Sri Lanka. It was just too hot to handle.

Do we — as citizens and voters — have the capacity to heed such distilled wisdom? It’s not good enough to celebrate Ari’s eight decades of life or hail him as the Pride of Lanka.

Ari keeps on speaking for many of us who don’t have the right words, or the courage – or both. He is the conscience-keeper of our bruised nation.

We ignore this little man at our own peril.

###

Science writer and development communicator Nalaka Gunawardene considers himself a ‘critical cheer-leader’ of Sarvodaya. As a secular humanist, he has never felt out of place in Sarvodaya’s form of inclusive Buddhism. He blogs at http://nalakagunawardene.com