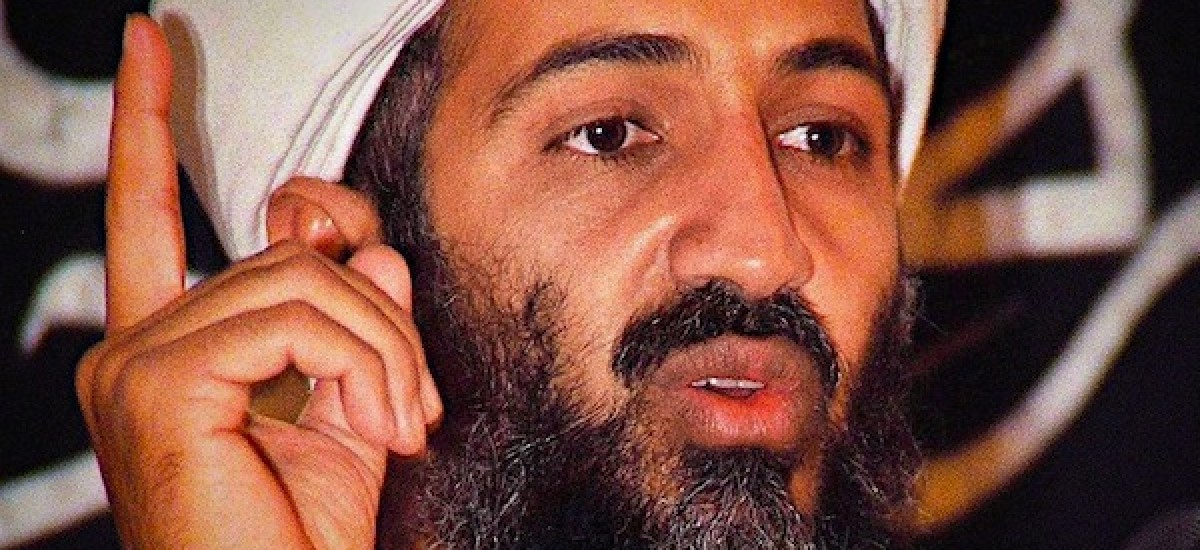

Photo: AP

Osama Bin Laden. Dark avenging hero, Arabian knight, Arabic Lawrence of Arabia. Osama versus the USA: David versus Goliath, a hijacked airliner the stone from his slingshot. Not quite. David didn’t murder Goliath’s family in their tents, leaving Goliath only hobbling. Not every leader or dramatic figure is a hero, and not every force that takes on a much bigger foe is heroic. Not even when that foe has been guilty, as has the USA, of horrible crimes such as the sanctions which were responsible for the deaths of several hundred thousand Iraqi infants.

This is not an argument for pacifism. Or moderation. Heroes are almost always extremists in one way or the other. They seem to seek out or get drawn into ‘extreme situations’ – in which they really come alive. They also ‘take it to the limit/one more time’. (The Eagles). They are not ‘one of ‘and do not comfortably ‘dwell among’. They are different from the rest. Like eagles, lighthouse-keepers or sentinels in a watchtower, they rise ‘above’ or range ‘beyond’ the average, the norm, the ordinary and everyday. They are often martyrs but are almost never angels or saints – purer, more decent than others in any conventionally comprehended sense. Being a-typical, they are not cosseted by and comfortably ensconced in the surrounding society, though there are moments of celebration and felicitation. They bear marks of a certain isolation caused by being out there in the vanguard, since being in the vanguard is a lonely, singular situation. The hero is worn, even misshapen by the wear and tear of going against the grain, of swimming against the tide, of being a voice in the wilderness. Thus he slips, commits mistakes, even crimes. Often his very achievements, including that of sheer survival and outstanding performance against tremendous odds, give him the sin of hubris. A hero is not a safe, regular person. He is dangerously destabilizing to others and dangerous to himself. He lives on the edge; walks the high wire. A creature of conjunctures, at other times he dwells in exile, often ‘internal’ or ‘spiritual’ exile. The hero is also almost always in danger, often of an unspecified yet permanent sort. He has made so many enemies in his odyssey that the danger inheres in the environment in which he exists – and he is so exhausted that he hardly retains his robust capacity to resist and prevail.

Somewhere on Mount Olympus, the Gods compensate for the exceptional strengths and abilities of a hero by giving him blind spots and (fatal) weaknesses. Like Achilles’ Heel. Without these he would be impossible. The hero isn’t a better human being than everyone else. He doesn’t have more endearing qualities. He just has those qualities – or those qualities in greater measure – that are needed to fight evil; for the survival of the community when it is in danger from Evil. In thought and/or in deed, he goes further and faster than most, he’s willing to take more risks. He isn’t good – he’s just better than the rest and morally superior to the enemy he finds himself opposed to and who opposes him. The hero may be horribly flawed; indeed this is almost a structural trait of the heroic profile. Take Othello, Oedipus, Ajax. He may hesitate, vacillate: Gary Cooper in High Noon. Christ at Gethsemane. He may have reprehensible insensitive, even self-serving behavior: Jason. But Jason got the Argonauts through, and it took him to do so. The hero is singular, almost unique. His exceptional qualities – those that enable the community to survive in times of mortal danger – alienate him from the community, sometimes leading to exile or self-exile, and often to his undoing. Hence the tragic hero: the Greek and the Shakespearean audiences knew that the hero must fall, and yet is redeemed in some ultimate moral or cosmic sense by his exceptional virtues.

DEATH SURPLUS

What then is the difference between a hero and Osama Bin Laden or Prabhakaran? Osama believes in a cause, he is deeply committed, is brave, takes enormous risks, has sacrificed himself, is decisive, is a rebel, is at the vanguard of the struggle against the rich and powerful global Establishment. Why then is he not my hero? Because each and every one of these characteristics could have easily described Adolph Hitler and Mussolini. These alone are not what define a hero. These are not enough. This realization on my part didn’t come easy. I had to think it through, re-think it, and wrestle with contradictory thoughts, feelings. But whatever the initial rush that came with the unforgettable, once-in-lifetime spectacle of the plane flinging itself into the Twin Towers, Old Testament retribution reaching out from the remote Afghan hills right into Babylon/Wall Street, I reached out for and tried to hold fast to a moral-ethical compass. It is evil to deliberately target innocent civilians. If you lose that moral compass in the struggle for change, the struggle against the status- quo, you lose direction and wind up in the same hell as Pol Pot and Hitler. You lose your soul.

The hero has a code. A code that is noble – and in the final analysis he lives or dies by it. Osama Bin Laden’s code is not a noble one. That is why he is not a hero. True a hero is an extremist and is often unbending, relentless, driving. But he is never a fanatic. A hero is intrepid, but struggles to steer, as did Ulysses between Scylla and Charybdis: between a capitulationist conformism which passively accepts the things that are, and ethical anarcho-nihilism which suspends all moral considerations in fighting against things as they are. What is the defining difference between an extremist and a fanatic? I submit that it is a question of ‘surplus violence’, ‘surplus death’. A hero never dispenses or causes wittingly to be dispensed, and indeed strives not to cause to be dispensed, a greater sum of violent death than is necessary. The violence is targeted against the forces of the enemy. The hero observes the distinction between the innocent and the guilty, the armed and the unarmed, combatants and non-combatants, armed men and unarmed women and children. A hero observes these distinctions and is able to make these discriminations, so difficult to do in the heat of passion – and the hero is nothing if not passionate.

There is an intimate connection between a hero and action, often between a hero and violent action. But what guides that action? A hero never engages wittingly, intentionally, in avoidable cruelty – and if he has done so he agonizes in repentance. That is a defining aspect of his heroism. A fanatic is characterized by the untroubled use of ‘surplus death’ i.e. an unwarranted excess of lethal violence. Indeed excess is celebrated. Bigger bangs. More deaths. He does not observe vital moral distinctions. The Vietnamese, who had four times more bombs dropped on them by the US than were dropped in the whole Second World War, never set off a single bomb in the USA. Fidel Castro who had more assassination plots against him hatched or backed by the CIA than any world leader, never conspired to kill an American leader. The ICRC has in its archives a letter from Fidel and Che, written while fighting in the Sierra Maestra, requesting aid that would enable them to continue treating captured Batista soldiers according to the Geneva Convention. Japanese soldiers, belonging to an army that had perpetrated the Rape of Nanking, found themselves treated scrupulously by Mao’s Liberation Army. That is heroic sensibility in action – as opposed to the ferocity of fanaticism.

HEROISM, FANATICISM

Che Guevara was an extremist, but never a fanatic, while Osama bin Laden and Velupillai Prabhakaran are fanatics. This is also why Fidel Castro is a real hero, while bin Laden and Prabhakaran, though leaders – and ones of great military accomplishment – are not. And it is also why those communities (ethno-religious, ethno-national) and individuals who regard the latter as heroes, should take a long hard look at themselves.

Che, who loved puppies, once had to order the strangling of a puppy that latched onto his guerrilla column on an ambush, because the puppy’s barks were betraying the hiding place of the guerrillas and would have resulted in them being wiped out. Che obviously felt so lacerated by the experience that he confessed the incident in a short story. In Talequan, Northern Afghanistan, the Taliban herded the population into the main town square. Then they paraded a number of dogs, on whose foreheads had been stenciled the names of their enemies – including King Zahir Shah and George W. Bush. They poured petrol on the dogs and burnt them alive. It was meant as a warning, said eyewitnesses (identities given in the news report) who arrived at a refugee camp. (The Telegraph Group, London/The Island Tues 2nd Oct, 2001 p6). When the Taliban took power in 1995, they dragged former Afghan ruler and Communist Najibullah out of the UN compound in which he was sheltered in accordance with the negotiated settlement, castrated him while alive, dragged him through the streets tied to a jeep and finally hanged him in public. A report in France’s Le Point somewhere in the year 2000 (I think it was April-May) quoted an LTTE cadre code-named Marianna, as disclosing that captive Sri Lankan soldiers are bled to death. The report went uncontradicted by the Tigers. This is barbarism of a very Dark Age.

The choice posed by History is no longer ‘Socialism or Barbarism?’ but ‘Democracy or Barbarism?’ Neither from the objective point of view of social progress nor from the subjective point of view of ethics and morality, can Osama Bin Laden nor the Taliban, Prabhakaran and the LTTE, or fanatics and fundamentalists anywhere, be humanity’s heroes.