Photo credits: 888 Sport Zone and Daily Info Picks

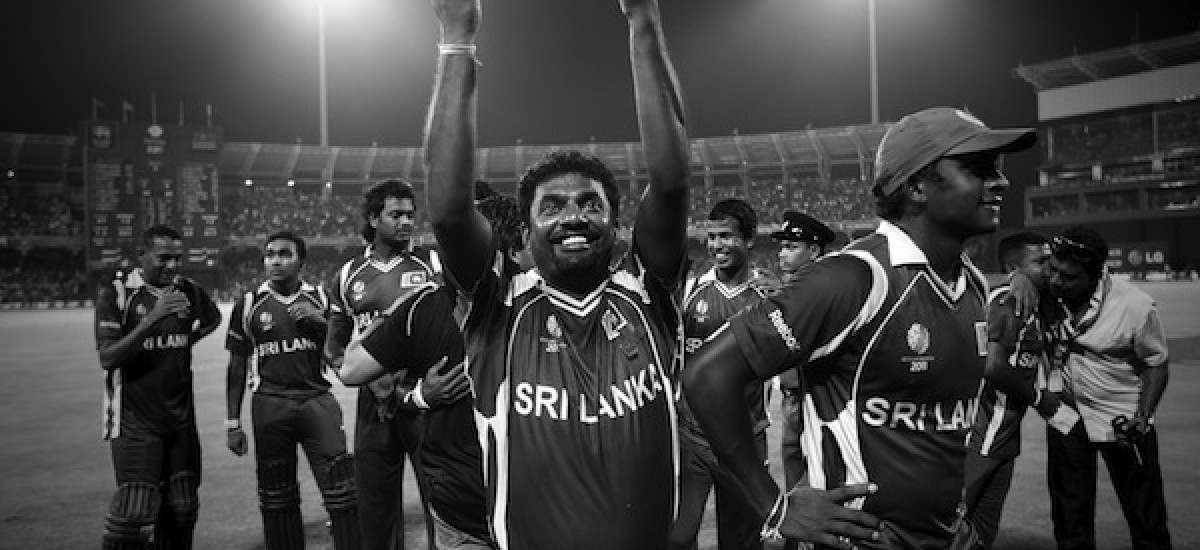

I know absolutely nothing about cricket and honestly would not have paid attention to the Cricket World Cup, had I not been in Sri Lanka the week its team made it to the final. Although the Sri Lankan team lost in the end, it was an electrifying moment to live, even as a foreigner. World Cup fever is universal, whatever the game, whatever the continent. The tension was so palpable, emotion and excitement at its highest on Galle Face Green where I went to watch the game amid a crowd of 8000 cricket fans. People seemed proud to be Sri Lankan, waving the flag, faces painted and broad smiles. An entire country behind its team.

This was particularly interesting, as Sri Lanka will be soon celebrating two years since the end of the war and mostly reconciliation between the different ethnicities remains a theory. Being Sri Lankan still largely means belonging to the dominant Sinhala/Buddhist culture. However supporting a national team implies that one feels part of a nation and the fervour following the semi-final that Sri Lanka won against New Zealand prompted many to wonder if a victory could help foster reconciliation.

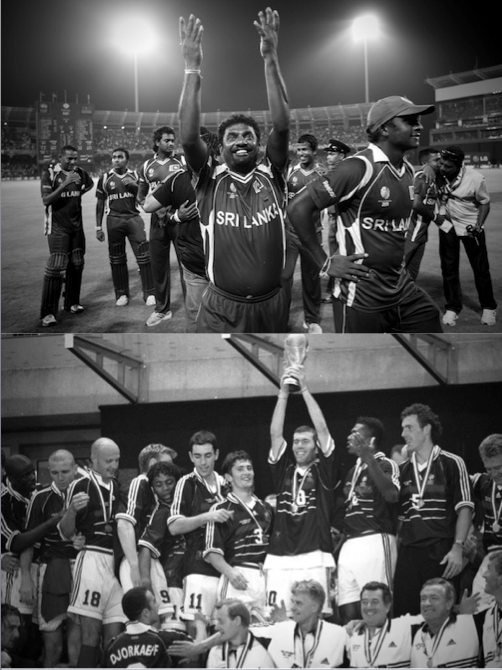

I could not help but think about 1998 and the football world cup that France won against Brazil and our own delirious state of French nationalism. I was 12 at the time, on a holiday with my family in Rochefort for a cousin’s wedding. Because we were all staying in a hotel, some twenty of us decided to watch the match in one of the room, in front of a ridiculously small TV screen. My cousins and I had painted our faces blue, white and red, the colours of the French flag, matched our outfits and even tinted our hair with blue, white and red hair spray. I barely knew the rules of the game, but men, I was into it. We were all. The whole of France was stuck behind its TV screen, in the streets, all over Paris, the suburbs, the province. We were all « black, blanc, beurre ».

This formula coined by the media was derived from the flag’s colours (bleu, blanc, rouge) and replaced them with skin colours representing the different ethnicities in the French team and France as a whole. « Black » for people of sub-Saharan origins, « blanc/white » for boring people like me and « beurre /butter» for people of Maghreb origins whose skin is the colour of melted golden butter. I remember the euphoria, singing «Et 1, et 2, et 3 – 0 !!!!» as Zinedine Zidane head-butted the ball in the Brazilian goal, twice, on two corner kicks, taking the French team to a total and triumphal victory. What a sublime game it was. I remember going in the street with my cousins, overwhelmed by the number of people out partying together, carrying flags and dancing on the pavement, on walls, in fountains. We felt like one people.

Fast-forward 7 years later, I am 19 studying in London and once again I find myself glued to a tiny screen -a computer this time- watching the news coming out from France with my good friend Pierre. Cars burning, riots, the suburbs of Paris, Lyon, Marseilles, Bordeaux, Nantes on fire because a disenchanted youth has decided to voice its anger for being relegated to second class citizens. From afar it looks like France has gone to war with itself. The young people in the streets are sons and daughters of 2nd, sometime 3rd generation immigrants, parked in the ghettos that are the state housing estates located in the suburbs around big cities – la cité, immortalised in Mathieu Kassowitz’s film La Haine. That France « black, blanc, beurre » that we so eagerly celebrated in 1998 seems to have never existed and I watch in disbelief. What did I miss?

What I missed is simple. When we watch a football game or a cricket game, we watch it with our friends, with people similar to us. The feeling of unity, comradeship is real, but what we celebrate is different from one group to another. Zidane the Algerian, like Murali the Tamil, are idolized by entire countries yet what the majority and the minority project on them is fundamentally different. While for the minority they are a source of pride and the proof that they deserve the respect of the majority, for the majority they are the proof that integration is possible without compromise, that those in the minority who complain really are just nuisance. Unfortunately for the racist and scared majority, “National identity is not only a football team winning when it is blue, white, red. It is a multicolour society; and that you have to deal with it in difficult times as well as in success”, as Tariq Ramadan, an European academic, pointed out.

Leaders like to do just that, hijack sport events like the cricket world cup, ride the wave of nationalist enthusiasm and proclaim heroes the players of minority origins, heroes they will be able to shake like scarecrows against the trouble makers who ask for equal rights. They appropriate to themselves the symbol of national victory, something as trivial as a football game, to create an easy discourse of unity. Perhaps I should stop here before I put Foucault and football in one sentence, but you get the idea.

France never really recovered from the riots in 2005. Since then the « identity » issue has grown, engulfing immigration, the « banlieues », “Islamism”, extreme right, populism and political opportunism. For sometime the Sarkozy administration has even tried to create a controversial debate on national identity, i.e. what it means to be French.

What does it mean to be French or Sri Lankan? I have absolutely no clue.

My point is flags, national anthems and national sport teams are all nice symbols meant to consolidate the Nation-State, an old 19th century concept that we struggle with in the global age. But the truth is nation-building is a bloody and insensitive process that wipes out minorities, forcing them to adapt to the majority’s culture and values to survive. It is a process at odd with increasingly universal values of human rights and democracy, but we cling to it because it reassures us. Football and cricket world cups and other international competitions are rituals in which we can reassert our belonging to the nation. Games are ersatz of battles and the mirror offered to us by multi-ethnic sport teams, champions duelling for their country’s honour, is infinitely more pleasant than the one where we kill, oppress and exclude to ensure that only our idea of what our country is prevails.

But of course, it’s just a game.